This week 50 years ago saw the release of A Touch of Class, a romantic comedy about two middle-aged professionals—a British divorcee and married American man, both with children—trying to have a clandestine affair that is initially a comedy of errors, then turns serious, then fails anyway. It was a moderate sleeper hit, in part due to the chemistry between stars George Segal and Glenda Jackson, as well as admiration for her (then) rare stab at comedy. Still, it was a shock when she won the Best Actress Oscar for it the next spring, marking the both her second win and the second time she hadn’t attended the ceremony to accept it. (Both times someone else gave a very generic speech on her behalf, this time Class’ writer-director Melvin Frank.)

But perhaps more surprising still is that A Touch of Class was also in contention for Best Picture—alongside American Graffitti, The Exorcist, Cries and Whispers and The Sting (which won). In a year whose releases also included Last Tango in Paris, Paper Moon, Mean Streets, The Last Detail, Day for Night, Sisters, O Lucky Man!, Badlands, Don’t Look Now, The Holy Mountain, Serpico, The Wicker Man, and Sleeper. It rapidly became one of those Oscar-winning movies nobody ever revives, because it wasn’t all that good to begin with—though Jackson certainly is good in it—and has dated poorly.

Still, it was probably the biggest mainstream success for an actress who was at the top of her profession in an era not very favorable to actresses at all. Such was the general poverty of women’s big-screen roles that her last nomination in 1975 was for a movie almost no one saw (Hedda), and the award went to Louise Fletcher in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest—a part that in any other year would logically have been classified as “supporting.”

But then Glenda Jackson’s career was upstream all the way. Child of a bricklayer and cleaning lady, she was a scholarship student at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in the mid-50s, but found it hard to get work for a while. Her big break occurred when she played Charlotte Corday, the assassin of French Revolutionist Jean-Paul Marat, in Peter Weiss’ innovative play-within-a-play musical Marat/Sade—both in Peter Brooks’ 1964 Royal Shakespeare Co. staging (which traveled to Broadway) and his 1967 film version. She became a bona fide movie star (and got that first Oscar) for Ken Russell’s 1969 interpretation of D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love.

In it, she was so striking—and so strikingly paired with the Oliver Reed, another atypical yet somehow inevitable new star—that ostensible leads Alan Bates and Jennie Linden sort of faded into the wallpaper. Her Gudrun was sharp-edged, mercurial, too intelligent for a woman of ordinary means in this just-post-WW1 era; her dissatisfaction is doomed to drive Reed’s possessive Gerald off the deep end. There was nothing ingenue-soft, trivial or merely “pretty” about Jackson, photogenic as she was. Indeed, some of the more backward critics would always have a problem with her not being conventionally “beautiful” or “charming” enough. Her technique was like an Exacto knife—it cut right through the nonsense.

The next decade was her peak of fame, but underlined the difficulty of finding vehicles worthy of her: The occasional prestige (Sunday Bloody Sunday) or commercial (comedy House Callswith Walter Matthau) success mixed with stuffy costume dramas, filmed plays, misfiring or underseen British dramas, the odd European production. By the early ’80s she was finding more rewarding work on television, and back on the stage—I made a catastrophic mistake in 1985 not seeing her in O’Neill’s epic Strange Interlude. (A friend insisted we go to Pygmalion instead, simply because it was shorter, thus trading Jackson’s reported brilliance for Peter O’Toole drunkenly fumbling his lines and bumping into furniture at a matinee.)

In her mid-fifties, grousing that soon there would be nothing left but to play “Juliet’s nurse,” she quit acting for Labour politics—spending much of the next quarter-century in Parliament. Those who missed her theatrical performances were perhaps consoled by her regular, ferocious, composed verbal decapitations of Tory representatives. Their visibly exasperated, “damned impudent woman!” tut-tutting only underlined her accusations of old-school elitist indifference towards the working class. You can find some of those impromptu speeches on YouTube, and they are a joy.

After leaving public office she returned to acting, most notably onstage in revivals of Three Tall Women (winning a Tony) and King Lear—yes, as the king, gender-blind casting her natural authority made seem perfectly natural. She passed away last week at age 87, though we have not seen the last of her yet: Scheduled for posthumous release later this year is The Great Escaper, in which she plays the wife of Michael Caine, as she had 48 years earlier in The Romantic Englishwoman.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

That last-named film, an intriguing if not-wholly-successful divertissement from the lofty minds of Tom Stoppard and Joseph Losey, is among Jackson titles available from Kino Lorber and its Kino Now streaming platform. Others include a reprise of her acclaimed TV role as Elizabeth R in 1972’s Mary Queen of Scots (who’s played by Vanessa Redgrave), she and Susannah York in excellent form as Jean Genet’s The Maids (1975), and 1987’s Beyond Therapy, one of two underwhelming collaborations (the other being H.E.A.L.T.H.) with Robert Altman. Some of her best screen work can be found elsewhere, like a turn as poet Stevie Smith in 1978’s Stevie, and as the childhood love of Alan Bates’ amnesiac WWI veteran in 1982’s The Return of the Soldier.

——

Recent releases to home formats (including Blu-ray) by Kino Lorber are led by Marcel Ophuls’ four-hour 1969 The Sorrow and the Pity, an extraordinary, excoriating yet dispassionately even-handed excavation of French collaborationism during the Nazi-controlled Vichy regime. When the Allies won, suddenly revisionist history held sway, and almost everyone claimed to have been in (or at least in sympathy with) the Resistance—just as post-WW2 there was scarcely a professed ex-Nazi to be found in Germany. But Ophuls finds people (many still just middle-aged) to contradict that narrative, including actual Resistance fighters who all too clearly recall the scorn with which they were treated at the time. He also includes enough contradictory voices to underline the residual power of collective denial.

That denial was bourn out by the film’s own reception at home: Originally made for television, it was rejected as unsuitable, going unreleased in France for many years. The indictment of French anti-Semitism, concentration camps on Gallic soil, rubber-stamping of fatal “deportations” (including hundreds of children), et al. was still considered to be too incendiary for public consumption. The film didn’t make it to the U.S. and several other countries until 1972, where it was quickly acclaimed as a nonfiction masterpiece. Incorporating vintage propaganda and newsreel footage alongside latterday interviews, it remains one of the greatest celluloid grapplings with the messy realities of war and occupation…which are so often so much less heroic than what the history books choose to record.

Discomfited French commentators argued that Ophuls had made the French “look bad” in part because of his family background—late father Max Ophuls was a German Jew who had to abandon his highly successful directorial career in that nation’s film industry when the Nazis came to power. He then worked elsewhere in Europe, mostly France, before again having to flee, this time to the US in 1941. It took him a while to gain traction there, though eventually he made several acclaimed features. He returned to France in 1950, completing a final quartet of sumptuously romantic and cinematic melodramas before dying of heart disease in 1957.

Another new Kino Lorber release is one of Ophuls Sr.’s last pre-war French films, There’s No Tomorrow. It stars Edwige Feuillere as a glamorous “fallen woman”—a once-respectable widow and mother whose late husband’s disgrace has reduced her to employment in “the hottest club in Montmartre.” Let’s hope it’s hot indeed, since she and her fellow chorines wear very few clothes; it is suggested that discreet prostitution as well as partial nudity is among their duties. When she runs into an old lover (George Rigaud) who knows nothing of this downfall, she goes to great, risky lengths in order to keep him in the dark.

This is pure romance-novel tripe, albeit so beautifully done you almost don’t notice—the Kino blu-ray’s sparkling print restores all Ophuls’ exquisite taste in setting and camera movement. Tomorrow balances the aesthetics of a plush tearjerker with lighting atmospherics that anticipate his own Hollywood noirs a decade later (The Reckless Moment, Caught). It also surprises with its discreet yet casual nudity (among not just chorines but the heroine’s bathing son), reminding that European cinema was considerably less prudish than the American kind even eighty-odd years ago.

Unlike its Axis ally Germany, Japan’s film industry rebounded fairly quickly after WW2, in part because there was a willingness to deal with war’s harsh aftermath onscreen. The series Shitamachi: Tales of Downtown Tokyo, already in progress at Berkeley’s BAMPFA, provides evidence of that, among other things. Running through July 29, the retrospective highlights fictive portraits of the city’s more vulnerable, often vice-riddled poor districts, which invariably bore the brunt of larger societal changes.

Some of these features are famous, like Yasujiro Ozu’s 1953 Tokyo Story (playing this Sat/24)—a generation-gap tale widely considered one of the greatest movies ever made—or the prior year’s Ikiru, Akira Kurosawa’s own favorite among his films. (It was also recently remade as the British Living, with Bill Nighy.) Others are lesser-known, including Ozu’s 1947 Record of a Tenement Gentleman and Heinosuke Gosho’s Where Chimneys Are Seen. Both are stories in which struggling, discordant neighbors are thrown into further turmoil by the arrival of an abandoned child they must reluctantly take responsibility for.

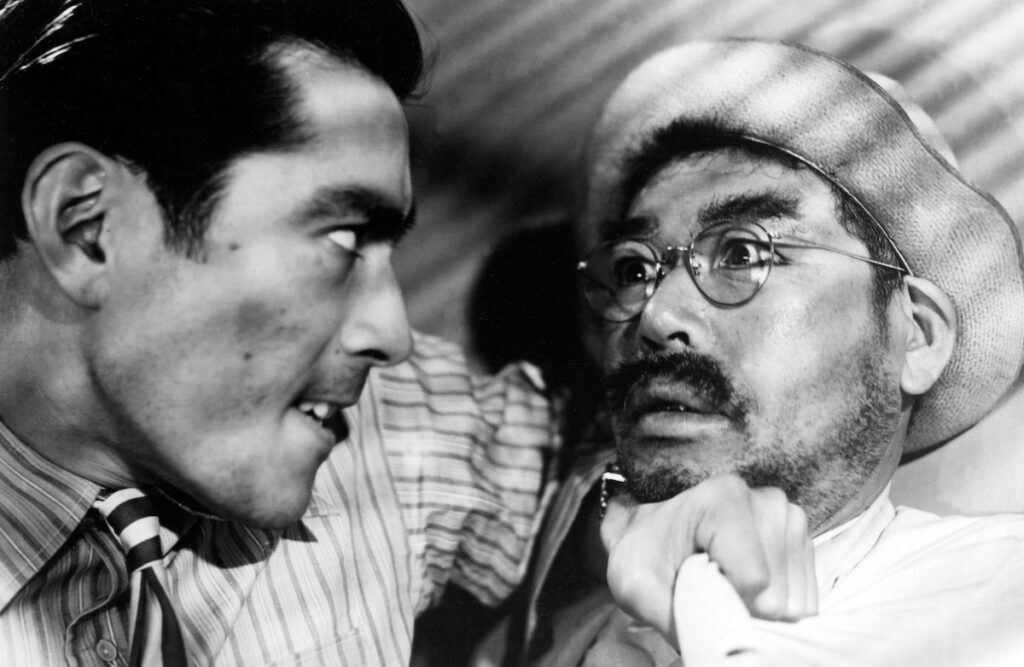

Similar seriocomic views of hard-luck communities are offered by Sadao Yemanaka’s 1937 Humanity and Paper Balloons, set in the 18th century Edo period; Yuzo Kawashima’s 1956 Suzaki Paradise: Red Light District, about a desperate young couple whose few options are all degrading; actress-turned-pioneering-female-director Kinuyo Tanaka’s 1953 Love Letter; and Kurosawa’s 1948 Drunken Angel, about the reluctant alliance between an inebriate slum doctor and a gangster with tuberculosis. Playing the latter was 28-year-old Toshiro Mifune, a near-unknown who was so electrifying, his director gradually increased an initially small role to co-starring size. Their collaboration would prove one of the greatest in film history, encompassing such classics as Rashomon, Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood and Yojimbo before a mutual falling-out in the mid-1960s.

Not the last film in the program, but the latest in terms of production, is Hirokazu Kore-eda’s 2004 Nobody Knows—a fact-based story of four young children abandoned in a Tokyo apartment by their mother, surviving in increasingly desperate circumstances. It was an early example of this director’s signature expertise with child actors and psychology, though also by far his bleakest dramatic use of those skills to date. For information on the entire Shitamachi: Tales of Downtown Tokyo series, go to https://bampfa.org/program/shitamachi-tales-downtown-tokyo