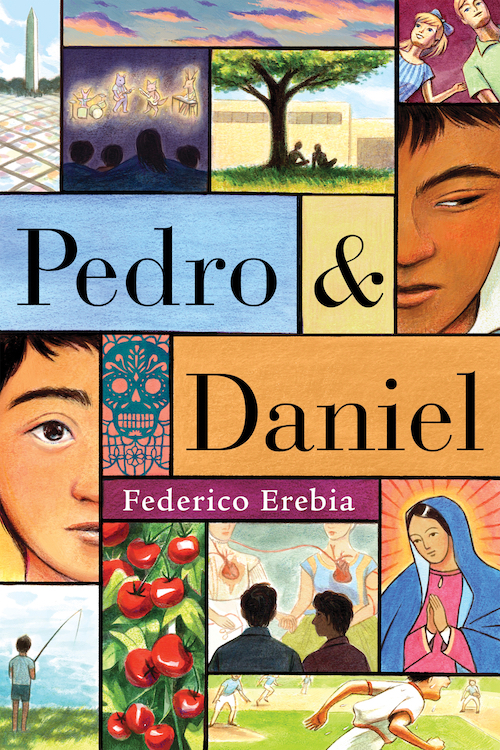

In Federico Erebia‘s semi-autobiographical debut novel, Pedro & Daniel, young Pedro tells his brother Daniel he would like to write their story one day.

And that’s what Erebia has done. On July 11, he will appear at San Francisco’s St Joseph’s Arts Foundation with Jaime Cortez, the author of Gordo, for a reading and discussion about the book closely based on the relationship he had with his brother, who died in 1992 at 30 years old.

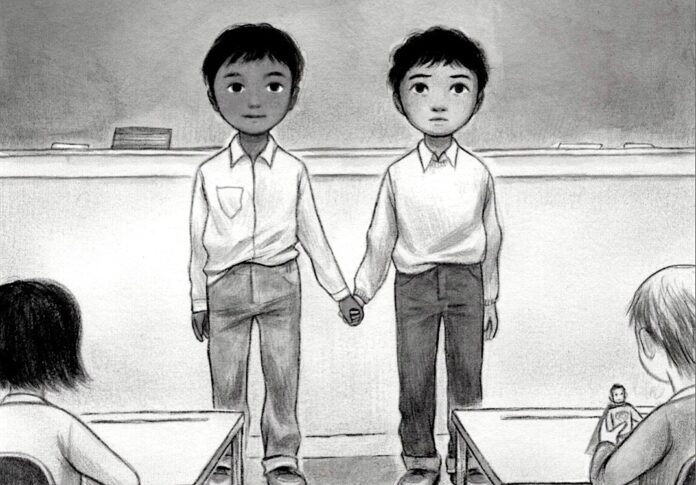

The book tells the story of the bond between them, both gay Mexican Americans who grew up in 1970s in Ohio. Their connection is illustrated in the first chapter. The children in Pedro’s kindergarten class have been told to bring a “true treasure” to school on the last day. Many bring dolls and dresses and baseball cards. Then Pedro, who is 15 months older than his brother, takes Daniel by the hand to the front of the room.

Pedro & Daniel is divided into five parts of the two as children, teenagers, and adults. The perspective shifts between first- and third-person narration, telling the story of the boys’ abusive mother, who wants them to play sports, and how they pursue their dreams of being a doctor (Pedro) and a priest (Daniel).

Erebia, who did become a doctor (and is now retired), said by video call from Massachusetts, that he’s been obsessed with writing the story for 30 years. During the pandemic, he got the chance. Clearly not afraid of a full schedule, Erebia took classes at the Rhode Island School of Design at the same time he was in medical school at Brown University, and he is also a woodworker.

When the pandemic came, he no longer felt comfortable going into people’s houses and he started writing. Erebia committed himself to it, going to conferences, taking classes, and joining writing groups. He met an editor who liked his writing and asked him to send everything he’d written and suggested combining the stories he’d written about himself and his brother into a book.

Writing that story was both painful and cathartic, Erebia says. He says the chapters from his brother’s viewpoint were his favorite to write.

“I had the liberty to make it completely fictional, based on what he had told me about some of those scenes that I recounted,” Erebia said. “I was able to make his roommate particularly funny. The evil priest who forced him to leave the seminary, I made him a caricature of that kind of a closeted self-loathing type of person. It was fun to imagine things from his perspective.”

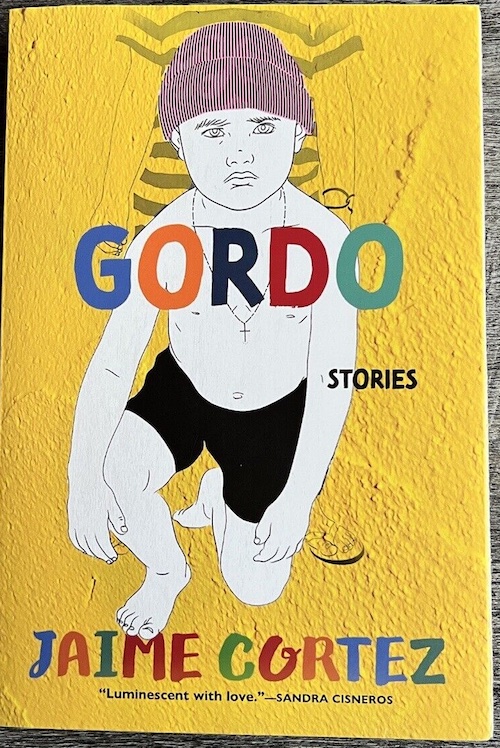

Gordo author Cortez, who lives in Watsonville, says San Francisco was where he became an artist and a writer, with his first reading at Café International on Haight Street in the early ’90s. Like Erebia, his book of short stories about a boy in a farm worker camp in the ’70s is based on his own life, and he looks forward to talking with Erebia.

“By pairing the two of us, they really are kind of creating a context,” he said. “Bringing one artist in represents just one person, but when you have two of them, and they’re coming from a rather similar perspective, and especially when it’s a perspective that we haven’t heard from as much, it feels significant.”

At a café on Van Ness, Cortez talked about wanting to keep his adult self out of room— and of the thoughts of the boy, Gordo, when he wrote the book.

“I wanted to get at the idea of a little kid who’s smart and observant, but not an adult in disguise,” he said. “I think one of the things that was fun for me with Gordo was how do I get this kid to explain these really rich concepts when he doesn’t have the language for it? What is the way that a kid finds the metaphors and the poetics to talk about the big questions?”

Cortez says he’s always been suspicious of the idea of a work of art being universal. But he’s been touched by the range of people that connect with his stories.

“I thought, well, it’s these Mexican American kids. It’s the ’70s. It’s a farm worker camp. That’s so specific,” he said. “I didn’t understand just how much the stories could bridge difference. I wasn’t ready for that, and I’m so delighted that it worked out that way.”

Cortez added that he sees a profound change from when he was growing up.

“In a rural community in the ’70s, in a farm town of immigrants, the amount of information that I had to work with to understand myself and my queerness was very limited and mostly hostile. Sometimes it felt like I was on the surface of the moon, it was that barren of others like me,” he said.

“I was kind of staggered a couple of years ago to learn that my niece, who at the time was 10, or 11, had joined the Gay Straight club at her school. And I asked my sister, ‘Is she kind of queer-identified? She goes, ‘No, she’s not. She says she just wants to be an ally.’ My heart cracked open.”

Cortez says he tried to use humor in his book, which deals with some heavy topics, like abuse and bullying.

Erebia also uses humor to tell sometimes painful stories. His brother was witty and sarcastic, he says, and they both loved Spanish proverbs or “dichos,” which he says appealed to their sense of humor. His favorite, Erebia says, is Para ser tonto, no se estudia, or “To be a fool, you don’t need to study.”

Like Cortez, Erebia is delighted with the response to his book. Recently he went to the American Library Association conference, and the book was so popular with the librarians that he ran out before his second reading.

“They really want books particularly for the queer and Latinx students who don’t have enough books that represent their stories, so they’re really excited about acquiring the book,” Erebia said. “I think about how there are kids and teens and adults who have never seen themselves in a book.”

AN INTIMATE READING WITH FEDERICO EREBIA & JAIME CORTEZ July 11, 6pm-8pm, free. St. Joseph’s Arts Society, SF. More information here