Robert Altman was an unlikely candidate to personify the New Hollywood of the 1970s. He was in his mid-forties when he finally had a breakthrough at that decade’s start, after nearly 20 years of laboring without much distinction in industrial films, independent features, and television episodes. Not much was expected from M*A*S*H, a relatively low-budget comedy about the Korean War, nor could Altman have been anyone’s first choice as director.

But the film’s loose, flippant air, its mixture of surgery gore and rude yoks, seemed subversively right-on to audiences made cynical towards military glory by the Vietnam War. At a fraction of their cost, it was even more popular than two much bigger, conventionally gung-ho war movies made concurrently at 20th Century Fox, Patton and Tora! Tora! Tora! It also heralded a new style that would become Altman’s trademark, with overlapping dialogue, a wandering camera, and ensemble-based storytelling focus that felt simultaneously amorphous and immersive—though when it misfired, that style could also make some subsequent efforts feel like rudderless failed experiments.

Still, it is remarkable that a sensibility so unique (though he would acquire imitators) managed to stay busy for another 35 years, to the year of his death in 2006 at age 81. A stubbornly nonconformist talent whose projects landed at nearly every studio and distributor imaginable, he scored many more misses than commercial hits—but every one of those flops has its fervent defenders.

And while Altman’s characteristic style was easily identified, he also sometimes stepped outside of it, particularly in a 1980s run of adaptations from stage works by David Rabe, Sam Shepard, Christopher Durang, and others that were surprising from a director notorious for treating his scripts very… uh, casually. (When a San Francisco journalist-turned-scenarist received the brunt of criticism for one of his most-dissed films, 1994’s starry fashion-industry expose Pret-a-Porter, she complained privately that there was almost nothing left of her screenplay in the finished product.) But then perhaps the most reliable thing about Altman was his unpredictability. His filmography reflects the restless curiosity of a mind forever drawn to exploring unfamiliar ideas and milieus.

That’s certainly illustrated by the 13 features in “Robert Altman at 100” (Fri/13 through August 30 at BAMPFA) the summer series observing his birth centenary at Berkeley’s BAMPFA. It is heavy on the Me Decade releases that established his auteur status, but also has much of the best of his later work: Atypically precise 1990 portrait-of-an-artist Vincent & Theo, which was originally made as a Dutch TV miniseries; acid Michael Tolkin-penned Hollywood satire The Player (1992); the next year’s kaleidoscopic mashup of Raymond Carver stories, Short Cuts; and 2001’s Gosford Park, in which the director turned out to be an inexplicably ideal choice to realize an Upstairs, Downstairs sort of classic British class dissection as written by Julien Fellowes.

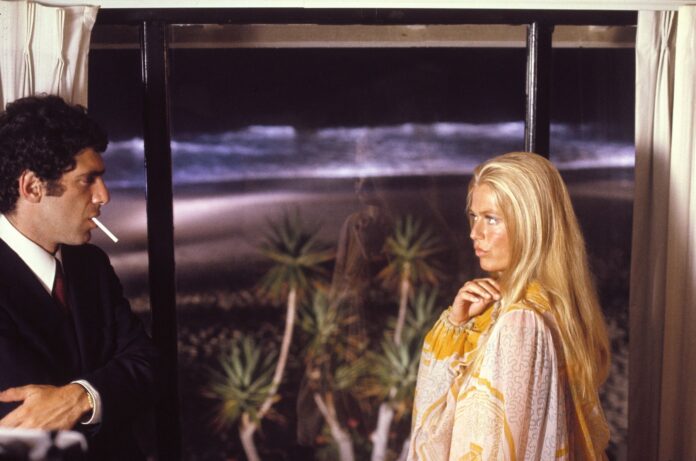

It is perhaps a tribute to Altman’s alchemical qualities as an artist that the 1970s “classics” here—starting this Fri/13 with perversely shambling 1973 take on hard-boiled The Long Goodbye, with Elliott Gould as a Philip Marlowe that Raymond Chandler would hardly recognize—strike me differently every time I see them. They’re unstable wonders, prone to hit you another way whenever they’re uncorked.

There’s M*A*S*H, which is far more anarchically messy than the subsequent TV show (which he had nothing to do with). 1975’s Nashville was the most celebrated of his cultural-cross section pieces, a music industry portrait loathed by its real-life models—and which accumulated such critical hype that few noticed how little headway it made with audiences outside urban centers. The 1971 McCabe & Mrs. Miller (those figures played by Warren Beatty and Julie Christie) is an opium-hazed frontier tragedy that now seems by far the best of all its era’s “revisionist westerns.”

All have their ample peculiarities. But the most eccentric films in this series (which encompasses just over one-third of Altman’s features) are a trio probing what may have been this director’s most perennially foreign-yet-magnetizing territory: the female mind as it approaches madness. 1969’s That Cold Day in the Park has Sandy Dennis as a premature Vancouver spinster who invites a seemingly homeless, mute youth (Michael Parks) into her home; simultaneously slack and affected, it’s an interesting idea that almost entirely fails to work in execution. In Ireland-shot Images (1971), Susannah York is a writer perhaps succumbing to schizophrenia. Again, the story is psychological horror, yet Altman seems disinterested in suspense, while his psychology is superficial. Still, the puzzle-like movie is very striking aesthetically. Flawed yet a sort of triumph is 1977’s 3 Women, a dreamlike construct with Shelley Duvall, Sissy Spacek, and Janice Rule that achieves the suggestive mystery and surface poetry of symbolist enigmas like Persona or Meshes of an Afternoon.

A contemporary of Altman’s who toiled in very different media—experimental as opposed to commercial cinema, plus the gamut of gallery arts—is also getting a posthumous retrospective at BAMPFA starting this weekend. “Bruce Conner: Films From the BAMPFA Collection” (Sun/15 and June 27) splits into two programs an overview of the longtime San Francisco resident’s short screen works. He pioneered the collage film with 1958’s A Movie, sewn together from miscellaneous preexisting footage (peepshow material, a Hopalong Cassidy western, travelogues, aerial disasters, bombings, car crashes) bought on the cheap. Its simultaneously antic and apocalyptic mic take on mid-century American life would be amplified further in 1967’s Report, which remixes visual and audio records related to JFK’s assassination—encapsulating the process of collective shock becoming collective myth.

More playfully still, Cosmic Ray (1961) and Breakaway (1966) bottle the “atomic age’s” sexy excess in rhythmic pileups of pin-up cheesecake, consumerism, and calamity. Their intoxicating dynamism would come to be considered a formative influence on music videos, with Conner himself dipping a toe into that nascent genre with clips for Devo (Mongoloid) and Brian Eno & David Bryne (America is Waiting). All these films and eight more will be encompassed by the separate BAMPFA bills. More info here.

The two very hip heterosexual filmmakers above are complemented by a couple choice revivals arriving in local theaters this week with new restorations. Applying modish techniques to a wispy romance between Parisian widow (Anouk Aimee) and widower (Jean-Louis Trintignant), Claude Lelouch’s 1966 A Man and a Woman (playing SF’s Roxie Theater on Sat/15) was an international sensation—perhaps because it distilled a certain notion of the ’60s that was all about jet-set Eurochic glamour, rather than war protests and hippies and such. It now seems like the movie equivalent of a glossy fashion magazine, a sleek empty package… but still goes down easy. Francis Lai’s score set the era’s standard for tasteful lounge music.

At some opposing scale-end, there is the B&W austerity of John Hanson and Rob Nilsson’s 1978 Northern Lights, a resourceful low-budget period piece that helped kindle the fire of the 1980s Amerindie movement. It dramatizes the WWI-era rise of the Nonpartisan League, a political party that sought to pry open the stranglehold predatory politicians and companies had on poor Norwegian-heritage farmers in North Dakota. This non-didactic, largely romance-driven portrait of proletarian activism, which won the Camera d’Or at Cannes, will be well worth a new look—the late Judy Irola’s monochrome cinematography earned comparisons at the time to the stunning visuals for another grain-fields flashback, Days of Heaven. Lights plays the Roxie beginning Tue/17, with further dates at Berkeley’s Rialto Elmwood (Wed/18), Marin’s Smith Rafael Film Center (Fri/20), and the Rialto Sebastopol (Tue/24), with Nilsson in person for some screenings.

This being Pride Month, however, there is plenty of LGBTQ+ content on local screens even before the Big Kahuna of Frameline arrives next week. Actually, the Smith Rafael is providing a prelude to that event with the third edition of its annual Pride series, with five Frameline selections being shown this weekend (Fri/20-Sun/22). Several filmmakers who’ll already be in town for the festival will attend. More info here.

CinemaSF is doing its bit in June with related titles at its three venues, notably including two cross-dressing Japanese cult items from 1969, Black Rose Mansion (4-Star) and Funeral Parade of Roses (Balboa). The 4-Star also has throuple-y Y Tu Mama Tambien, Wong Kar-Wai’s Happy Together and early Almodovar Pepi, Luci, Bom. At the Balboa there’s Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman, Sapphic youth comedies Bottoms and But I’m A Cheerleader, Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, and Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight. While the Vogue has Sean Penn as Milk, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and mainstream drag-a-paloozas To Wong Foo and The Birdcage. Theater schedules can be found here.

Of general planetary interest is Edivan Guajajara, Chelsea Greene, and Rob Grobman’s We Are Guardians, a beautifully shot documentary that takes a many-sided look at what’s happening to “the world’s lungs”—Brazil’s Amazonian rainforests, whose escalating clear-cutting is a major factor in climate change. Counting Leonardo DiCaprio and Fisher Stevens among its producers, the film hears from Indigenous protestors, impoverished, loggers, corporate farmers, investigative journalists, and agents of the Bolsonaro regime that prized economic growth over all else. The directors will be present at many screenings around the greater Bay Area, which include ones in San Rafael (Thu/12), SF (Fri/13, Sun/15), and more. For venues and showtimes, go here.