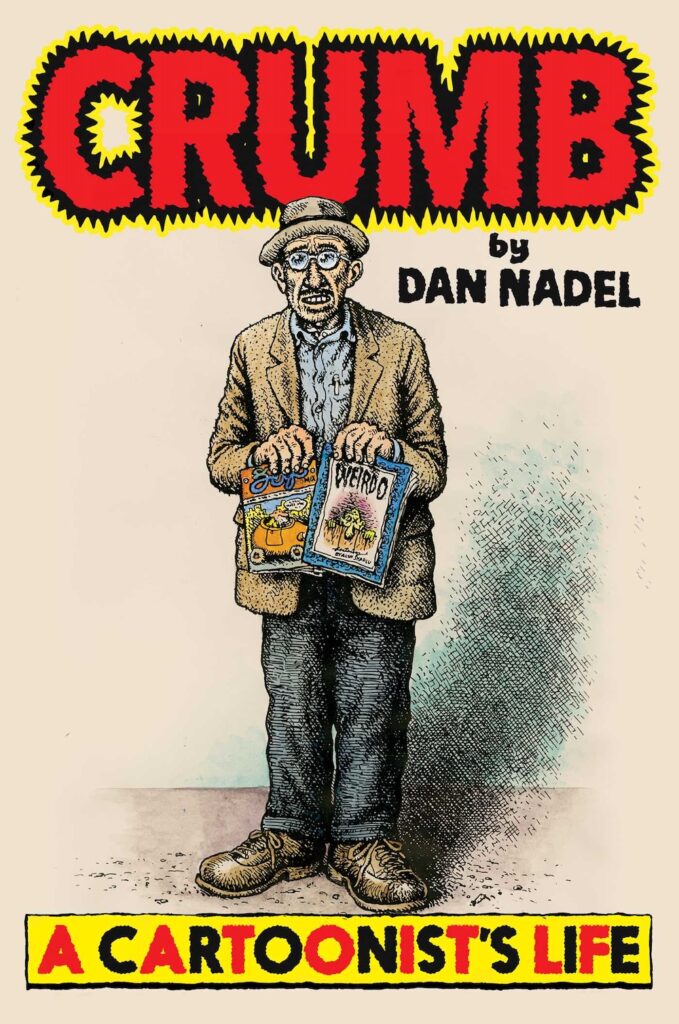

In a self-portrait on the cover of Dan Nadel’s new biography, Robert Crumb, the cartoonist renowned for his “underground comix,” holds two of his creations: Zap and Weirdo. He looks like he wants to sell the books, or at least show them off. Both were edited and drawn mostly by Crumb, began their lives in San Francisco, and were published by a company called Last Gasp.

Neither Crumb nor Last Gasp have yet taken their own final breath. They’ve survived, and continued publishing comics for decades—but also have become part of the last half-century’s cultural history, which Nadel documents with finesse in his new book Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life ($35, Scribner).

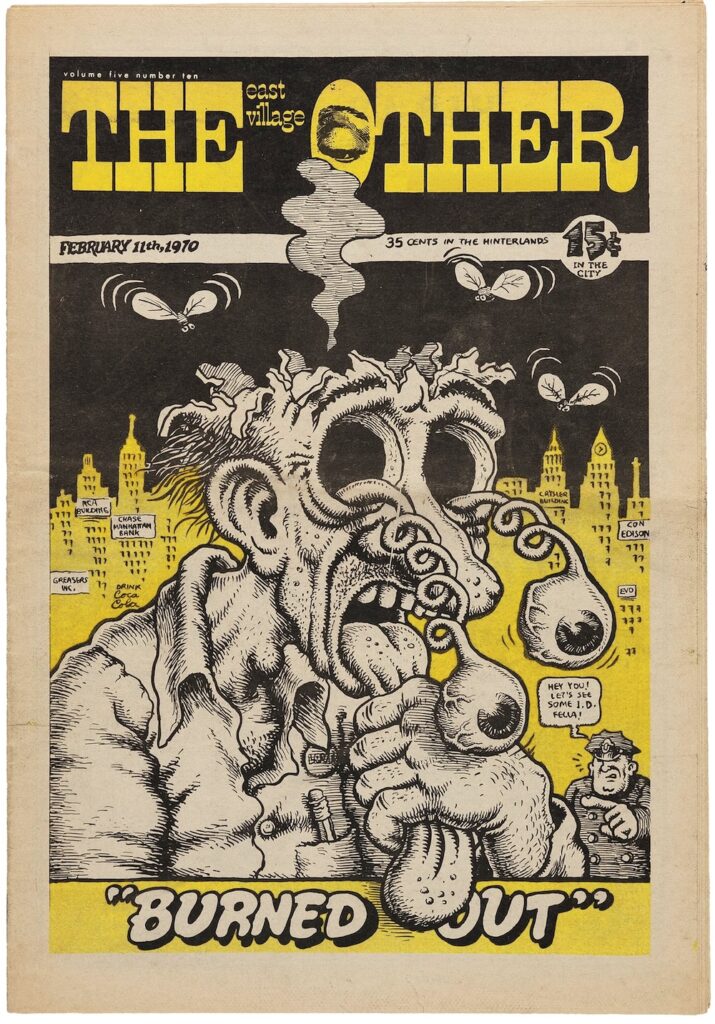

Today, first editions of old Crumb comix are costly collector’s items, rare books. Around 1968, you might have found him on Haight Street selling copies of Zap Comix for 50 cents. He was part of the local scene, along with head shops, Grateful Dead concerts, Golden Gate Park’s Human Be-In, the Diggers, the Free Store and free love.

In 1991, after years of artistic struggle and triumph in various rural and urban American locations, Crumb moved to a village in France, where he spent more than three years illustrating the Book of Genesis (yes, the Old Testament). While many of his earlier comics mocked modern foibles, Crumb found the Bible’s narrative “so bizarre in itself, there’s no need to satirize it.” His original inked pages (200 of them) sold for $2.9 million dollars to the new Lucas Museum for Narrative Art, after which the artist and his wife, fellow cartoonist Aline Kaminsky, created a few comics about their latest quandary: what to do with all that money?

In the first Crumb biography, Nadel (curator for the very Lucas Museum that paid out those millions) clearly appreciates the artist’s worth—and not just the man’s transition from low income to wealth, but also the aesthetic, social, and personal values held by the cartoonist that led to Crumb’s extraordinary drawings.

Crumb jokes about his San Francisco days in one 1982 comic strip titled “I Remember the Sixties.” It begins with an older, allegedly mature version of himself seated in a comfortable armchair, wearing a smoking jacket, holding a pipe in one hand, a small talking pig in his lap, nostalgically recalling his past: “Ah, the Sixties, I’ll never forget that wonderful wacky decade… the wild foot-loose days of my youth. I remember—I—jeeez, I wish I could remember. I’m so fuckin’ brain-damaged from all the drugs… all the trips.”

Despite his consumption of mind-altering drugs, or possibly because of it, Crumb remembered a lot over the years. He kept drawing wherever he went, and never fully ceased to be wacky and footloose (in a good way) as a cartoonist. Since the ’60s, he has continued to tell stories about weird, funny and cynical characters including himself and Aline in comic book formats. He also published several sets of illustrated trading cards (mostly showing old-time musicians), volumes of sketchbooks, and illustrations for writing about and by other writers such as Edward Abbey, James Boswell, Charles Bukowski, Kafka, Sartre, and whoever penned the Bible.

His prodigious creative work, plus books and films by others about him, have helped Crumb become a highly-praised, widely exhibited American artist… who now lives in France. He might even qualify as an old master, a satirist in the tradition of the Hogarth, Daumier, and Harvey Kurtzman (best known for his Mad magazine comics).

Nadel’s biography suggests that Crumb’s own life has been just as lively and full of unusual characters as his comics, possibly because some of the same people appear in both. Mr. Natural, Flakey Foont, Lenore Goldberg and the Girl Commandos, Angelfood McSpade, Joe Blow, Fritz the Cat, Priscilla Pig, plus other horny and talking animals are by no means simply portraits of the artist’s friends. The activities of his fictitious characters reflect some of the social and antisocial behavior Crumb saw around him in California and other states.

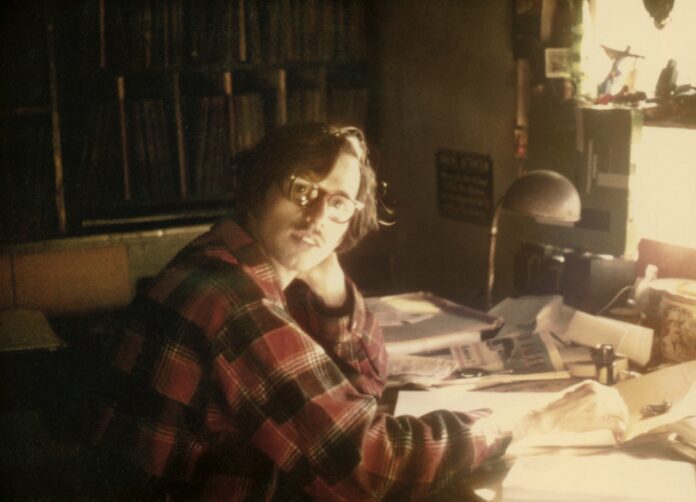

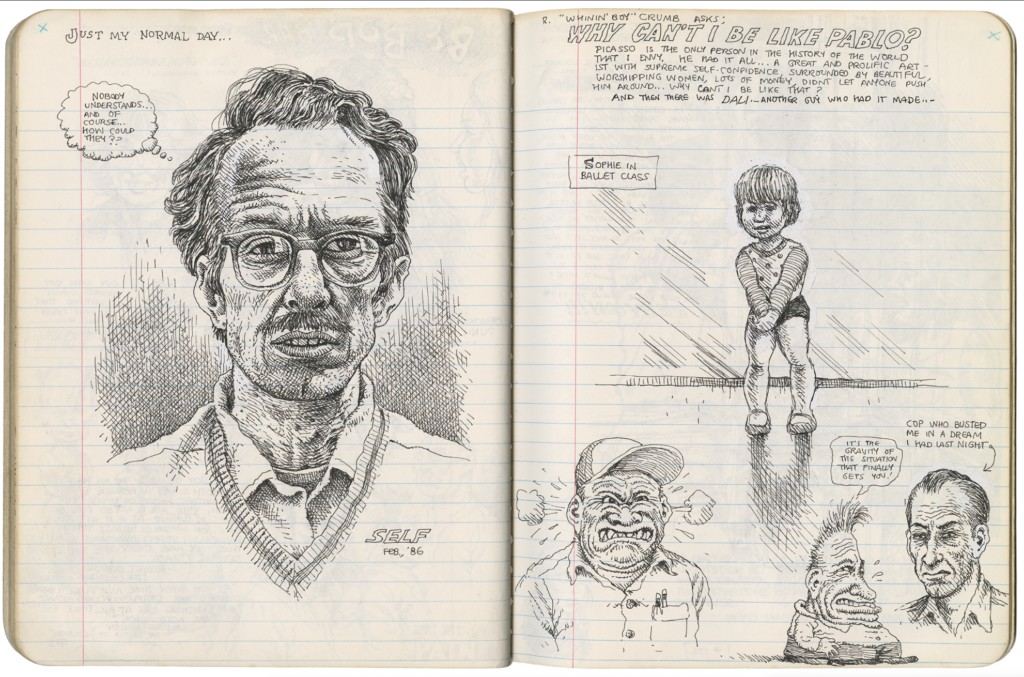

Benefitting from the author’s cooperation, having conducted conversations with Crumb and his peers and loved ones, Nadel reconstructs the artist’s life story. Readers follow the man from his childhood and school days, through his apprenticeship with a greeting card company in Cleveland where he met future collaborator Harvey Pekar, to his association with creators of Mad and Zap, and his periodic residencies in San Francisco. Reproductions of pages from Crumb’s comix and sketchbooks help readers see the genesis of his wildly original and occasionally LSD-influenced comic art.

Sex, drugs, funny animals and countercultural rejection of nine-to-five lifestyles receive considerable attention from Crumb. The drop-out and tune-in-culture of the ’60s is represented and mocked by white-bearded Mr. Natural, a sort of a rogue zen master whose disciples include Flakey Foont. Humorous self-reflection and self-criticism in some comics portray Crumb as a grumpy young man, later a grumpy old man, often horny, explicit about his lust, guilty about his white male chauvinist activities and his success as an artist—but also enjoying it.

The explicit, uproarious depictions of what’s on his mind, conscious and subconscious fantasies complete with naked and intertwined bodies, led some critics to condemn episodes in Crumb’s comics as obscene, racist, and sexist. A few comic book sellers had to pay a fine for allegedly selling the alleged pornography. Some issues of Zap and another Crumb creation, Snatch, were confiscated by the police.

The line between Crumb’s satires of prejudice and lust and less comic, more offensive behavior are sometimes hard to discern. That’s part of what makes his drawings outrageous, as well as riotously entertaining. I have to confess that I’ve had doubts about the humor in a strip titled “When the Goddamn Jews Take Over America!” and have been tempted to call it anti-Semitic. But this 1993 strip, and one linked to it showing Blacks taking over America, turn out to have been prophetic in their way, with the indignant narrator’s bluster anticipating our current era’s Christian nationalism, white supremacy, and continuing nuclear war preparation.

Crumb’s mocking, unflattering depictions of African-American and Jewish stereotypes led biographer Nadel to observe: “Robert took a lot of heat for this… His friends Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith said it didn’t work as satire, which it doesn’t. It works as a well-observed warning about the racism and antisemitism embedded in America, masked as cathartic art.” I suspect Crumb would say he was only joking when he drew these fantasies; not everyone will see the humor in them.

Throughout the biography, Nadel’s quotations from Crumb’s own letters to friends and from interviews suggest that the artist frequently has been offended by the behavior of other people: their acceptance of social conventions, conformity to social restraints, and his own temptation to conform lead him to deliver illustrated rants, verbal protests, and mocking portrayals of the offending parties.

One offensive act not relocated in a comic strip is cited by Nadel from a letter Crumb sent his publisher. The cartoonist objected to the timidity and cowardice of Viking Press when it was afraid to print a book cover in which Fritz the Cat fondles a breast.

“YOU GUYS ARE A BUNCH OF CHECKEN-HEARTED, NAMBY-PAMBY, NERVOUS NELLY MUTHAFUCKAS!!!” writes Crumb, and that’s only his opening endearment. While manic in its insults, the letter is only slightly different in tone from the very funny, self-absorbed self-criticism Crumb hand-letters in some comic strips berating his own demented behavior.

In his strip remembering the ’60s, for example, Crumb recalls “I too was obnoxious… I too ‘came on’ to the girls… I too had contempt… I too was brought back to reality by the new feminist line;” but the seemingly serious self-critical confession is undermined by a picture of an angry woman endlessly berating Crumb as he bows his head and whispers to her, “I’ll be good, I promise.” An arrow points at him, its words warning: “Not to be trusted.”

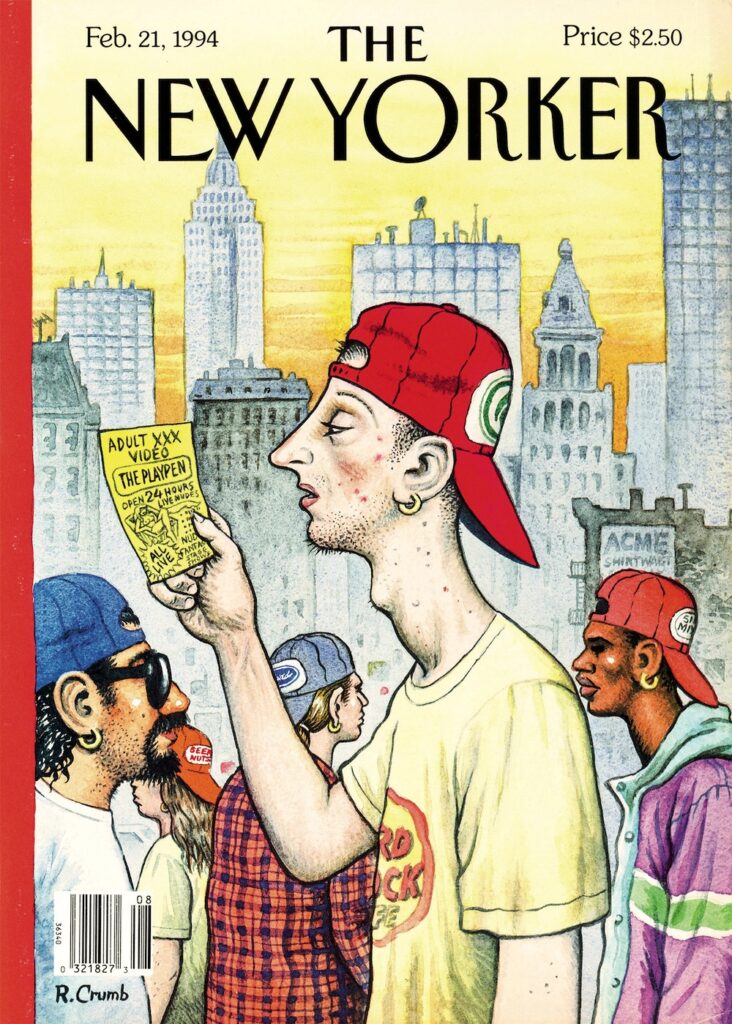

While Crumb may be best at mocking his own variable disposition, his lusts, prejudices, purported failures, sellouts, and bouts of despair, he also proves to be a fine social and political satirist when he attacks other people’s faults. One of my favorite Crumb drawings in this category is his 2020 satire of Donald Trump co-drawn with Aline Kominsky, and titled “Bad Diet Bad Hair Destroy Human Civilization.” (See it here.) First printed in the New York Review of Books, this masterfully executed gibe, along with some of the couple’s full-color New Yorker contributions, takes Crumb and Kominsky far from acid trips of Zap Comix into the world of New York intellectuals, although these newer works may attract some of the same old readers, like me, who followed Crumb to other publications besides comic books.

Nadel’s biography ensures we know that there’s much more to Crumb’s life than comic books. Friends, relatives, lovers, editors and fellow cartoonists make frequent appearances. Then there are episodes about the book and animated film, Fritz the Cat; about Terry Zwigoff’s film that documented Crumb’s life and art in 1994, and won the artist new followers around the world; about the pirating and far-reach of Crumb’s illustrated slogan advising audiences to “Keep on Truckin’,” which inspired the Grateful Dead song “Truckin’.” Other stories are told about Crumb collecting rare 78-speed records, and playing old-time music with a band called the Cheap Suit Serenaders.

Crumb’s influence on the evolution of comic art also receives consideration in Nadel’s book. While the cartoonist has achieved international recognition, his determination to depart from the restrictive “Comics Code” and turn comic books into adult reading matter (one cover of Zap advertised that it was for “Adult Intellectuals”) also helped clear the way for other artists to introduce neglected and controversial topics in their comics. Crumb and his colleagues at Zap inspired some of the current creators of graphic novels and graphic history books, as well as the creator of “The Simpsons”. For years all of Zap’s contributors were men, which led Bay area women including Trina Robbins and Aline Kominsky to start Wimmen’s Comix, which in turn inspired other, more recent comics and graphic novels by Alison Bechdel and her peers.

While Crumb sometimes mocked ’60s radicals, in The People’s Comics, his free speech and freer drawing-hand were followed by artists and publishers more open to overtly political comics such as World War 3, featuring art by Sue Coe, Peter Kuper, Eric Drooker, Sabrina Jones—illustrators who promote social change by ordinary people, not superheroes. Crumb’s good friend and Zap contributor Spain created a graphic history of Che Guevara, and Spain’s book editor, Paul Buhle, commissioned other artists to create a series of radical graphic histories about Emma Goldman, the Wobblies, Partisans, Paul Robeson, Herbert Marcuse, and the socialist and Jewish Labor Bund. Crumb may not want this wide-ranging comics legacy attributed to him; and it shouldn’t be, entirely. But he knew some of these innovators and influenced many more of them with his pens and ink.

At the end of Nadel’s biography, Crumb is alive and still drawing past the age of 80, which could be considered a happy ending. After having read this new book, and then re-reading some of his comics, I can now imagine Robert voicing his own assessment of Dan Nadel’s biography. Seated in an old rocking chair, sporting a French smoking jacket and a beret, the aged but smiling R. Crumb closes the Nadel tome, turns to face his readers, and says: “Friends, there will be difficult days in your life as a comic book artist, lonely and gloomy days when your gallery refuses to hang that new series of sketches, and your book publisher files for bankruptcy. But if you read Dan Nadel’s biography of me, an enjoyable, gossip-filled read—well-illustrated, by the way—you’ll have to agree, the world may laugh at you and call you an ink-stained clown, but that’s OK in this profession. A world of fame and fortune awaits you in the funnies.”