When “The Golden Girls” premiered in the fall of 1985, it wasn’t framed as a cultural corrective or a bold act of television radicalism. It was sold as a sitcom with a clever hook: four older women sharing a house in Miami, consoling each other, helping each other, advising each other, and talking candidly about sex. Oh, and there was plenty of cheesecake.

At the time, television rarely knew what to do with women over 50 unless they were mothers, widows, or punchlines, and audiences weren’t expected to follow characters like Dorothy, Rose, Blanche, and Sophia into conversations about politics, grief, ambition, or rage, let alone the bedroom.

Forty years later, “The Golden Girls” has outlasted nearly every assumption made about it. The series hasn’t merely survived as nostalgia; it has evolved into a cultural touchstone—rediscovered by younger generations, embraced by queer audiences, staged live in productions including “The Golden Girls” Live: The Christmas Episodes (running at the Curran Theatre through December 21) and pop-up experiences, theme restaurants, documentaries, memes, and proof that network television once trusted its audience to handle complexity. For longtime fans of the series, “The Golden Girls: 40 Years of Laughter and Friendship: A Special Edition of 20/20,” currently streaming on Hulu, is not to be missed.

What began as a network gamble now reads like a blueprint.

That endurance is usually credited to the show’s four leads—Bea Arthur (Dorothy), Betty White (Rose), Rue McClanahan (Blanche), and Estelle Getty (Sophia)—and to heroic creator Susan Harris’ writing.

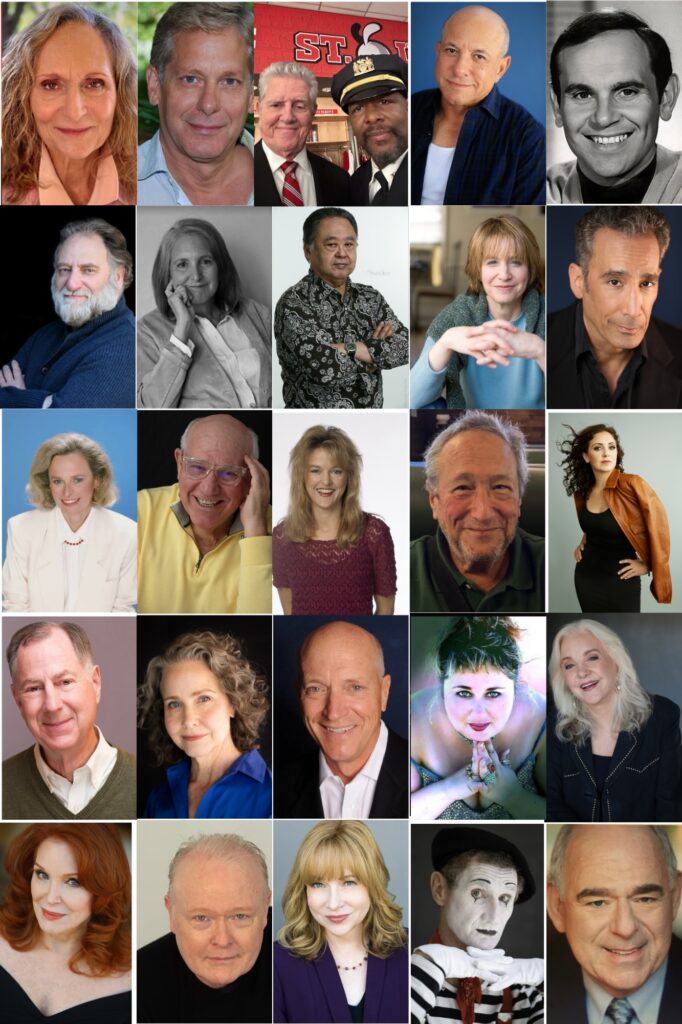

But “The Golden Girls” is also the story of the dozens of guest actors who passed through that Miami house—often for a single episode—and walked into a working environment unlike any other sitcom of its era. Together, their memories sketch not only a great show, but a way of making television that’s become rare.

Again and again, those actors describe the same sensation upon arrival: a shift in the energy.

Park Overall, best known as Laverne Todd on the “Golden Girls” spin-off “Empty Nest” and in films including Mississippi Burning, felt it immediately when her character debuted. “There was a different air,” she says. “A different vibration of professionalism.”

What struck Overall wasn’t warmth, but seriousness of intent. “The Golden Girls” wasn’t a loose, joke-driven set where charm covered mistakes. It was a workplace with expectations. Preparation, precision, and time mattered—and Overall traces that rigor straight to the page. “Number one, and first and foremost, is the genius of Susan Harris,” says the actress.

Scripts were constantly refined, sometimes rewritten right up until the final taping, and actors were expected to stay flexible without losing command of the material.

Veteran Groundlings member and “Pee-Wee’s Playhouse” writer Doug Cox (who appeared as Sven in “Yokel Hero” and as Mr. Lillestrand in “Not Another Monday”) remembers rewrites happening during dinner breaks because the laughs weren’t quite right yet. “That’s how seriously they took it,” he says. Comedy wasn’t something you hoped would land; it was something you engineered.

Stand-up comic Thom Sharp remembers last-minute changes when he played funeral home director Mr. Pfeiffer in “It’s a Miserable Life,” and immediately understood there would be no margin for error. “You had to deliver,” says Sharp. “You couldn’t panic.”

For “As the World Turns” and “Facts of Life” alumnus Scott Bryce, who appeared as Dr. Warren in “Once in St. Olaf,” the show’s rigor crystallized during a scene opposite Bea Arthur that simply wouldn’t land. Instead of letting the tension settle on the guest actor, Arthur intervened. “She said, ‘It’s not this actor’s fault. It’s the line,’” Bryce recalls. Responsibility on “The Golden Girls” was collective.

Legendary comedian Ronnie Schell (best known for his work on “Gomer Pyle: USMC”), who played prospective car buyer Thomas in “Triple Play,” remembers even physical details being treated with the same seriousness.

“They put lifts in my shoes so I could be Bea’s height, because the episode ends with a date with her,” he says. “I thought I was too young and too short to play the part, but I was so grateful to be on the show that I put on my lifts and took her out.”

Nothing was arbitrary. Blocking, bodies in space, rhythm—everything served clarity.

Sam McMurray, who’d already appeared in 1987’s Raising Arizona and on “The Tracey Ullman Show” before playing con-artist Mr. Kane in “Cheaters,” recognized immediately that this was not a show built on improvisation. “The humor wasn’t improvised,” says McMurray. “Scenes lived or died on structure.” Precision wasn’t a bonus; it was the baseline.

Emmy-winning “Boston Legal” actor Christian Clemenson, appearing as a shady alarm salesman in “Break In,” remembers being struck by how seamlessly everything already functioned. “That show was very smooth,” he says. “Especially for it to be early in its first season then.” The steadiness wasn’t ease—it was maintenance.

For many guest actors, that rigor found its clearest expression in Bea Arthur.

Arthur has often been mythologized as intimidating or complex, what Schell calls a “tough cookie,” but those who worked with her describe something more exacting. “She was not interested in being liked,” says Overall. “She was interested in getting it right.”

Arthur didn’t perform warmth or waste time on false intimacy. What she offered instead was authority grounded in fluency—an absolute command of the show’s rhythms, contradictions, and tonal balance.

Overall remembers Arthur as blunt, profane, intellectually serious, and intensely private. One moment still makes her laugh: Arthur stepping out of her car barefoot, thick book in hand, dismissing small talk with a profane aside.

“I asked her, ‘What are you reading, Bea?’” she says. “‘I’m reading John le Carré.’ And she looked at me like I was nuts and said, ‘I like a lot of sucking and fucking,’ and walked off.” It wasn’t rudeness, according to Overall; it was economy.

Having been cast to play Dr. Chang in “Sick and Tired: Part 2,” “Deadwood” actor Keone Young arrived on set after repeated warnings to be careful around Arthur. He prepared obsessively, determined not to waste her time. What he encountered surprised him.

“She was a true professional,” says Young. When the scene landed, Arthur’s response wasn’t effusive praise—it was a blown kiss. “That was everything.” It also won him the role of Mr. Tanaka two seasons later in “Rose: Portrait of a Woman.”

Future “Nip/Tuck” and “All’s Fair” writer Lynnie Greene experienced Arthur’s approval differently when she played Young Dorothy four times across three seasons.

“I studied everything about Bea Arthur’s physicality, everything about her voice,” Greene says, to fully inhabit the younger version of Dorothy in flashbacks. Arthur didn’t flatter. She watched. When she smiled, Greene knew she’d passed the test.

Jaclyn Bernstein, who appeared as a child playing Linda in “Letter to Gorbachev,” absorbed that seriousness instinctively. “These women were at the top of their craft,” she says. “And the nicest of people.” Comedy, she learned, wasn’t casual. “With comedy, timing is everything,” says Bernstein. “It felt like dance choreography.”

That choreography could be ruthless. Celebrated mime Derek Loughran remembers a terrific physical comedy idea he had for “The Auction.” When Sophia tells him his fly is down, he’s supposed to check it and fall. In rehearsal, Loughran ad-libbed a suggestive rope-pulling and tucking-in gesture that killed the room—then got cut for disrupting the rhythm.

“It was still a good moment for me because I got to crack everybody up,” Loughran says. “And these are experienced professionals who are hearing funny stuff every single day, all year long.” Even laughter itself was managed so dialogue wouldn’t be swallowed.

Authority on “The Golden Girls” wasn’t about fear. It was about precision.

That discipline extended beyond performance into character itself. Overall recalls resisting early impulses to flatten her role into a Southern caricature. “I wasn’t going to do that trashy Southern stuff,” she says. “This wasn’t dumb, ignorant hillbilly.” Rather than punishing that resistance, the show absorbed it. The writing adjusted. The character deepened.

That flexibility defined “The Golden Girls” as a writers’ show—but not a rigid one. It trusted actors to recognize when something rang false, and it trusted audiences to follow nuance rather than shorthand.

Shawn Schepps, who played Blanche’s daughter, Rebecca, in “Blanche’s Little Girl” before becoming a successful TV/film writer, remembers how the show handled complex subjects—verbal abuse, body image, family estrangement—without apology. Coming out of those four characters’ mouths, it felt less threatening.

“It was comforting,” says Schepps. “People were comforted when watching it. And that’s why it never went away, because it made people feel, in some way, safe. Besides all the great artistry, it just made people feel good, comfortable, and secure.”

Kyle T. Heffner (best known for roles in films like Flashdance and When Harry Met Sally) recalls the weight of playing Sophia’s late husband, Salvador Petrillo, as a young man in “Clinton Avenue Memoirs,” a character defined by absence.

“I basically went in and did the closest impression of Sid Melton [who played older Salvador eight times on the show] that I could muster,” he says. “And they decided to give me the job.”

During a table read, he also received a smack on his face from none other than Arthur after an off-the-cuff joke. “It was more of an affectionate smack,” says Heffner. “It was like, ‘Shut up, kid. You don’t have to say that. Just read your lines.’ It was adorable.”

The writing demanded restraint rather than sentiment. Silence mattered. Implication mattered.

Future “Star Trek: The Next Generation” actress Rhonda Aldrich remembers that even broad characters, like the sex worker Meg in “Ladies of the Evening,” were grounded in emotional truth.

“Honey, I played a lot of hookers in those days,” she says. “I played a hooker on ‘T.J. Hooker.’”

But there was something more fleshed out about Meg. “She was kind of like the hooker with the heart of gold,” adds Aldrich.

She credits the impact of the brief jail scene with Betty White to the writing, acting, and staging by longtime “Golden Girls” director Terry Hughes. “We’re down there in the center of the room on that bench with all the other hookers behind us,” says Aldrich. “So it really focuses on it.”

Scarlet-haired Sondra Currie (of The Hangover franchise and real-life sister of Runaways singer Cherie Currie) recalls being allowed to be a rival without becoming a joke as Margaret Spencer in “Big Daddy’s Little Lady.”

When McLanahan took issue with Currie’s “competing with her” for camera time, director David Steinberg took Currie to lunch to soften the blow of cutting much of her part and even her face time.

“People used to say you should get a hair commercial from that show because I was always shot from the back,” Currie jokes. Comedy emerged not from humiliation, but recognition.

Future “Brooklyn Bridge” and “Heroes” actor Alan Blumenfeld, cast as Lou the plumber and children’s entertainer Mr. Ha Ha in the first two seasons, remembers realizing quickly what kind of show this was.

Charm wouldn’t save you here. “The humor lived in structure,” he says. The writing assumed intelligence on the part of both the actor and the audience.

What many of the guest actors describe—sometimes without naming it directly—is the rare experience of being taken seriously inside a comedy. Not indulged. Not flattered. Taken seriously.

Richard Tanner (“Empty Nest,” The Glimmer Man) remembers realizing years after playing Young Stan on “Dateline: Miami” that it was the credit people most wanted to discuss.

“When I say, ‘I did ‘Golden Girls,’” says Tanner, “it’s always, ‘Oh my God, you did ‘Golden Girls’? Who did you play?’ And all I have to say is ‘Young Stan,’ and they say ‘You were Young Stan?’ I feel like they think that I was on more than once.”

To this day, when he runs into series writer Marc Cherry—who wrote the episode before going on to create “Desperate Housewives”—he’s greeted not by name, but by “Young Stan.”

Stuart Pankin, who played slimy hotelier Jacques De Courville in “Vacation,” recalls a similar delayed understanding: in the moment, it felt like a well-run set.

“When I was on the set, all the women were nice and friendly and open to the guest cast,” Pankin says, who’d go on to become friends with Betty White. “That doesn’t happen all the time.”

Only later did its rarity become clear, which he credits to the actors’ talents, the writing, and the growing empathy with and interest in these characters as we age.

Theater veteran Lenny Wolpe, who played predatory Arnie in “Dateline: Miami,” remembers the lightheartedness on set that week since Bea Arthur was off.

He also recalls knowing almost immediately what kind of comedy this was—and what kind it wasn’t.

“When you watch the show, it is genuinely funny,” says Wolpe. “First of all, you have those four ladies who were brilliant comic actresses. The writing was so phenomenally done. And then those four gals could tell jokes. The show also featured gay characters like Blanche’s brother, Clayton (Monte Markham), and Dorothy’s friend Jean (Lois Nettleton) in such an original and funny way.”

Emmy-winning “St. Elsewhere” star Bonnie Bartlett, who was up for the role of Jean but ended up playing novelist Barbara Thorndyke in “Dorothy’s New Friend,” recalls the difficulty of being unfunny while attacking Rose and Blanche.

“I mistreated her friends,” says Bartlett. “But subtly. It was like I had seen my mother do things like that, and I could do that easily because I saw some of that.”

Bartlett says Barbara Thorndike became memorable because of her humourlessness.

“She is not to be liked,” she says. “That’s why that show particularly stood out because it wasn’t funny in the way she treated the women who everybody loves, as if they were just uneducated… You love to laugh with them, but don’t make fun of them.”

For Deena Freeman, who’d recently exited “Too Close for Comfort” when she appeared as Dorothy’s daughter, Kate, in “Son-in-Law Dearest,” the professionalism was notable precisely because it wasn’t announced. It revealed itself through process.

“I did my work preparing for the role, but then what you do is you show up to the set, and when you’re working with the other actors, you just take it all in and allow yourself to live the role,” says Freeman. “And there were just such phenomenal actors and producers on that set.”

That process required trust. Actors were expected to make choices—but only if those choices served the whole.

What emerges from these recollections is a portrait of a set that understood comedy as labor. Timing, tone, and emotional calibration were work. And because it was treated that way, guest actors didn’t feel like ornamental extras. They felt necessary.

Veteran stage actor Ron Orbach, who played overworked civil servant Dan Cummings in “Sophia’s Choice,” about seniors falling through the cracks of the social system, articulates one reason the show could weigh in on pivotal topics.

“They could tackle homosexuality and other subjects because they were old ladies,” he says. “Nobody could say shit to them.” Age became armor, not limitation.

That freedom extended to the audience as well. Viewers weren’t talked down to. They were trusted to catch implication, to sit with discomfort, to laugh without cruelty. That trust is one reason the show remains so legible to younger generations now encountering it for the first time.

“Herman’s Head” and “Walker” star Molly Hagan, who played Miles’ daughter, Caroline, in “Triple Play,” puts it plainly. “It’s deeper than the humor,” she says. “You’re getting their wisdom, their experience.”

Blumenfeld wouldn’t fully grasp the impact until years later, when fans began approaching him to talk about what the show had meant to them.

“Dozens and dozens of people,” he recalls—often speaking about coming out, about feeling seen.

For the actors, it was simply work—serious, demanding, collaborative work. The meaning came later.

That delayed recognition mirrors the show’s own trajectory. What premiered as a “cute” sitcom revealed itself over time as something sturdier. Not radical by proclamation, but radical by consistency. It insisted, week after week, that women’s inner lives were worth the time it took to render them honestly.

For all its rigor, the set was not cold. It refused to substitute sentiment for craft.

Lee Garlington (who was shooting “Lenny” on the same lot) remembers Betty White’s generosity, after she played her daughter in “Home Again, Rose: Part 2,” as something active rather than performative.

“Betty invited me to go with her, as she had rallied hundreds of actors year after year, down to a children’s hospital for burn victims, some with Spina bifida, others with broken bones, and people who will never breathe or talk or walk on their own,” says Garlington. “We would walk into a room, and she would light it up, and we’d smile and talk. Between rooms, I’d find a supply closet, and I would weep. I don’t know how she did it. She did it with aplomb, grace, and panache. She was just a fantastic human being.”

Speed, Sordid Lives, and Little Miss Sunshine actress Beth Grant, who appeared twice on the series (as newsroom employee Terry and Daughters of the Confederacy member Louise), remembers McClanahan’s generosity as practical: memorize the lines, but don’t fossilize them.

White went further, stopping taping to acknowledge her publicly after she nailed every rehearsal and take. “As a young actress at the time, it was thrilling to be singled out like that by her, and oh, they all gave me a big round of applause,” she says.

That care extended to Getty as well. While Getty’s memory struggles are now part of the show’s lore, Overall—who often sought her advice, mirroring how Dorothy, Rose, and Blanche always asked Sophia for her advice on the series—remembers her as wise and approachable.

“I loved Estelle above all else,” she says. “She was so wise. Everything about her was so warm and real, and she was a great comfort to me on many levels.”

Forty years on, as the actors describe their memories so vividly, the Miami house still feels open. The arguments still resolve into laughter without erasing disagreement. “The Golden Girls” didn’t ask its audience to be polite. It asked them to be human.

And that, more than anything, is why it remains golden.

“THE GOLDEN GIRLS” LIVE: THE CHRISTMAS EPISODES Through 12/21. Curran Theater, SF. Tickets and more info here.

“THE GOLDEN GIRLS: 40 YEARS OF LAUGHTER AND FRIENDSHIP — A SPECIAL EDITION OF 20/20” is currently streaming on Hulu.