F.W. Murnau is best known now for one of the most famous among silent movies, although it narrowly missed instead being one of the most famous lost silent movies. The 1922 Nosferatu was a horror film made at a time when that genre was not yet a screen staple, its imagery so disturbing that a legend arose that lead star Max Schreck was a “real” vampire, or at least believed himself to be—a tall tale eventually spun into the 2000 film Shadow of the Vampire, with Willem Dafoe memorably playing the actor-bloodsucker. (In real life, Schreck was simply a versatile stage and screen actor who continued playing many diverse roles for the remainder of his life.) The film’s own mystique was such that in 1979 it was remade by another iconoclastic German director, Werner Herzog, with the inimitable Klaus Kinski offering an equally unearthly performance.

But the original Nosferatu almost vanished into celluloid history, because its screenplay was an unauthorized blatant rip of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. That author’s estate successfully sued for copyright infringement, with the result that the producers declared bankruptcy. All copies of the film were destroyed by court order—all save one that somehow escaped the pyre. That sole print became the source for all others as the film gradually developed a cult following, as well as critical acceptance as one of the masterpieces of silent German Expressionist cinema.

Something equally furtive and rescued-from-the-ashes remains about Murnau’s too-short career in general: He died far young (in a 1931 car accident, aged just 42), leaving behind a small but imposing body of features from which over one-third are presumed permanently lost. He was of the generation of directors that survived World War I (in which he’d been a fighter pilot) to make Germany’s film industry, at least briefly, the most advanced in the world. Like many peers, his talent attracted the attention of Hollywood, where he migrated when that industry had wrested global supremacy by the mid/late 1920s.

The BAMPFA series F.W. Murnau: Voyages Into the Imaginary, which opens this Sat/8 and runs through February, offers a mix of his famous classics (from both sides of the Atlantic) and those lesser-known titles that survive, all shown in recent digital restorations with live musical accompaniment.

Friedrich Wilhelm Plumpe was the bookish, artistically inclined scion of a Prussian clan prosperously involved in textiles. He changed his last name when his family initially disappointed of his entertainment-world career, clandestinely begun while he was still ostensibly studying to enter academia. Swept into the circle around legendary theatrical innovator Max Reinhardt, he didn’t seem destined for great things as an actor, but became more intrigued anyway by becoming a director himself. After the war, he turned those ambitions toward film, drawing on already-extensive contacts in the Berlin art world (including the actor Conrad Veidt) with extraordinary industriousness. He released six features in less than two years, all of them now lost.

Five of the next six films (including Nosferatu) survive, however, and all are in the BAMPFA series. None are “great,” but they’re remarkably accomplished for their era, reflecting the high polish of German film studios at the time as well as Murnau’s own sophisticated use of imagery, atmosphere, and nuance—even when his actors occasionally insisted on a more hammily “theatrical” style. 1921’s Journey Into the Night is a “tragedy in five acts,” a somewhat leaden morality play whose quadrangle of marriage-busting desires (including Veidt as a blind man reminiscent of his somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) is nonetheless always interesting in interior design and exterior location choice. Ditto that same year’s The Haunted Castle, a murder-mystery potboiler juiced by a couple brief dream sequences, one frightening and one comedic.

His preference for somber melodrama, which much later some would liken to Ingmar Bergman, bears richer fruit in films made just before and after Nosferatu in 1922. The Burning Soil is a bleak, wintry tale of greed indulged and repented, as the promise of oll-well riches pits brother against brother, daughter against stepmother. In Phantom, very different kinds of obsession bring ruination to a family: One son throws away his life pursuing a specter of female beauty always just beyond reach, while his sister flees the misery of their widowed mother’s household, ending up in exactly the position of sexual exploitation that dour matron predicted for her. Both films have their share of hand-wringing histrionics, but are also striking in mood and look.

In 1924 Murnau bucked his reputation as a heavy dramatist via The Finances of the Grand Duke, a breezy mix of Ruritanian farce, romance, intrigue and adventure that isn’t terribly funny, but remains charmingly light as a feather. That same year, however, came the project that made Murnau a hugely sought-after talent: The Last Laugh, an audaciously “simple” (yet cinematically overwhelming) story of a hotel doorman—played by leading German star Emil Jannings, later an overenthusiastic supporter of the Nazi regime—whose pride takes a fatal blow when he is demoted to washroom attendant. Told without intertitles, but with extraordinarily advanced visual fluidity thanks to the technical innovations of the director’s frequent cinematographer Karl Freund (whose subsequent Hollywood career took him all the way to I Love Lucy), it was a worldwide sensation.

After the contractual obligation of a Tartuffe he didn’t particularly want to do (and it shows), Murnau made a third Jannings vehicle in the superior form of Faust, a phantasmagorical superproduction worthy of being considered alongside contemporary Fritz Lang’s Nieberlungen and Metropolis. It was a huge investment that failed to pay off financially for studio UFA (as did even-more-expensive Metropolis the next year). Still, it confirmed within the industry that the director was some kind of genius.

Ergo Hollywood made offers that could no longer be refused. Murnau made his first feature there in 1927, at Fox Film Corp. Sunrise, subtitled A Song of Two Humans, was considered such a creative apex for the medium that it won the very first Best Picture Oscar, albeit as “Unique and Artistic Production”—popular hit Wings got a separate-but-equal prize, a split designation the Academy would never repeat. Sunrise was indeed too, well, “artistic” to be a big box-office success. But the visual poetry it expended on an admittedly simple, cornball story (country bumpkin seduced by city vamp, pursued and redeemed by his pure-hearted wife) remains fairly dazzling.

The admiration accorded his vision should have put Murnau in a very strong position, professionally. But his next two features for Fox were frustrating experiences, as the studio was panicked by the new “talkie” craze, adding awkward, gratuitous sound sequences to each without the director’s consent. 1928’s Four Devils, a circus story with Sunrise star Janet Gaynor, ranks high on any list of most-sought-after “lost” films.

Shot the same year, City Girl was also thought lost for many years, until miraculously Murnau’s intended silent version was discovered intact. It’s sort of an “answer film” to Sunrise, this time with a purehearted urbanite (Mary Duncan) running off to the country for love of a farm boy (Charles Farrell), only to find the disapproval of his authoritarian father (David Torrence) destroying their happiness. That psychological dynamic is akin to the current Power of the Dog; the film was also reportedly a big influence on Malick’s Days of Heaven. Again, the script’s melodrama is banal, but Murnau’s sense of evocative image and editorial rhythm greatly elevates it. By the time Fox finally decided to release the thing in 1930, however, it seemed a relic of another era, and was ignored accordingly.

Hardly willing to be a complacent factory worker bowing to the bosses’ will, Murnau took these setbacks hard, preferring to break his Fox contract and set up productions independently. Thus he wound up partnered with like-minded Robert Flaherty, the famous documentarian (Nanook of the North, etc.), with the two deciding to film a tale of island tribal life on location in Bora-Bora.

But problems almost immediately arose: Funding fell through, forcing Murnau to finance the film itself; he also wound up directing on his own after disagreements of content and personality with Flaherty only escalated. The resulting Tabu: A Story of the South Seas was closer to the romantic, “exotic” escapism of movies like Bird of Paradise than the intended co-director had wanted. But it was also lovely to look at (Floyd Crosby’s cinematography would win an Oscar), with a sensuousness and degree of authenticity brought by the use of attractive local non-professional actors. As a de facto silent movie (there was a pre-recorded original score) released in 1931, it proved another commercial failure, but one whose reputation would steadily grow over ensuing decades.

Not that Murnau ever knew: A week before its premiere, he was killed in an accident when a teenage servant crashed his Rolls into a pole on the Pacific Coast Highway. Kenneth Anger’s notorious book Hollywood Babylon alleged that this was caused by the director being busy fellating his underage “chauffeur” (the official, adult chauffeur was also in the car) as he drove. But like so much else in that scandal-mongering tome, the story appears to have no basis beyond gossip, or perhaps simply that author’s well-known penchant for confabulation. It’s not even known for sure whether Murnau was gay, though that’s been taken for granted by many since, including an entire bio-novel (Jim Shepard’s Nosferatu, published in 1998).

Murnau remains an elusive figure. Considered cold and imperious by some, a generous collaborator by others, he did not care to open up the inner workings of his mind (or personal life) to the public. What might he have done had he lived? Returned to a Germany soon to lose itself in National Socialism? Abandoned the movies altogether, having resisted sound technology to the end? Given the prolific adventurousness of the span between his military service and demise, it seems unlikely he wouldn’t have continued to be a major cultural figure in some respect. But for someone who worked in an art form barely over a decade, F.W. Murnau left an indelible mark on that medium.

As it happens, this month Kino Lorber is releasing Blu-ray restorations of two early films by other German directors of Murnau’s generation (more or less), who also each went on to do significant work in Hollywood. After becoming famous primarily for lavish costume dramas starring the vampy Pola Negri, Ernst Lubitsch moved to the US and became a specialist in the sophisticated comedies that would culminate in a series of 1930s Maurice Chevalier musicals and brilliant romantic farces.

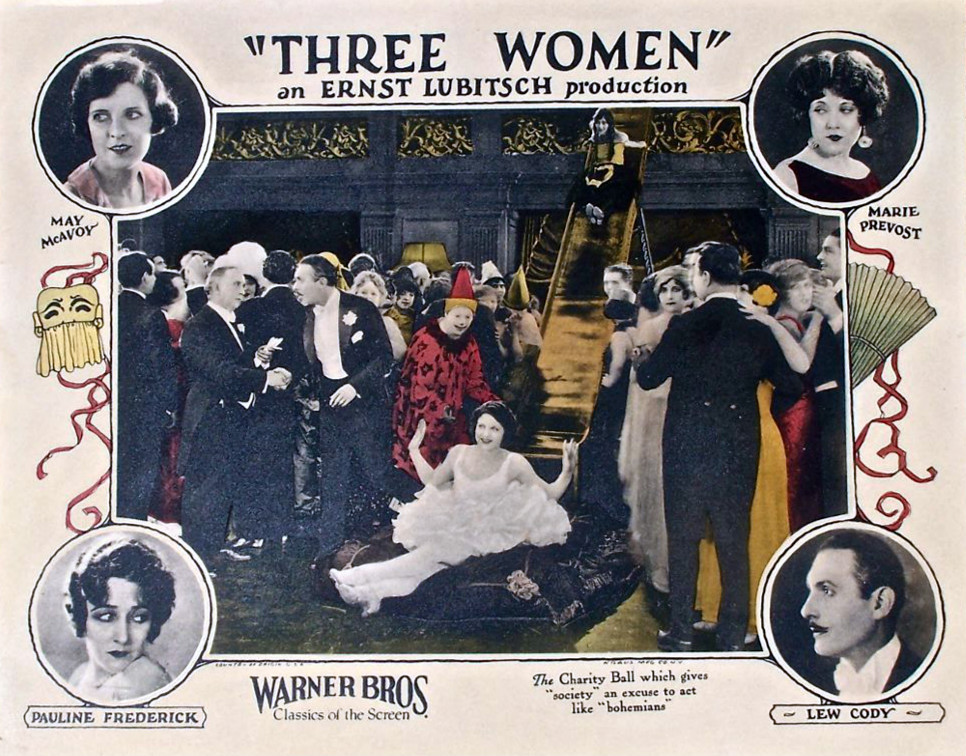

His third American feature, 1924’s silent Three Women (no connection to the Robert Altman movie of that same name 50-plus years later), would prove an anomaly in that it was almost the last time he attempted a serious drama. Yet much of it plays in the witty, innuendo-laden mode of his comedies, with the same plush settings and a lavish Jazz Age party scene (featuring a slide from balcony to dancefloor). Hounded by creditors, a scoundrel playboy (Lew Cody) seduces a wealthy widow (Pauline Frederick), then behind her back courts the woman’s wide-eyed collegiate daughter (May McAvoy), while still stringing along his own mistress (Marie Prevost). A hit then, it’s minor Lubitsch now, but still worth a look, with a very good original orchestral score by Andrew Earle Simpson.

Max Ophuls’ initial film career in his native Germany was brief—being Jewish, he fled the Nazis in 1933, then had to flee a successful run in the French industry when the Nazis invaded that country. His talent languished in America until the great Preston Sturges, a fan, got him launched in Hollywood. He made some fine films there (including Letter from an Unknown Woman and a couple notable noirs) before returning to Europe, where his last years were spent making several famous classics like Lola Montes.

The Kino release Laughing Heirs (1933) was released the same year as Liebelei, which made his reputation and was much more in his wheelhouse as a lush romantic melodrama. By contrast, this cheerful feature (his fourth) is pure fluff, involving mechanizations around the inheritance of a vintner’s estate. Frivolous, garrulous Peter (Heinz Ruhmann) is the chosen heir, his late uncle having spurned envious but joyless, teetotaling other relatives. But Peter will only gain the boozy empire if he can himself abstain for a month, something that those same relatives plot to undermine, as do parties from a rival company.

A project that was assigned to Ophuls by the UFA studio, rather than one he chose, Laughing Heirssometimes feels like an extended commercial for Rhineland tourism and sparkling wine. It’s also the kind of cheerful silliness one keeps expecting song-and-dance production numbers to intrude into, though they never do. Nonetheless, this uninspired material is given the proper degree of fizziness and gloss by Ophuls, who was no Lubitsch yet could certainly bring a similar Continental elegance to comic intrigue.

F.W. Murnau: Voyages Into the Imaginary runs Sat/8 through February 27 at BAMPFA in Berkeley, film schedule and more info here. Three Women (releasing January 18) and Laughing Heirs (January 11) are being issued on Blu-Ray by Kino Classics, info here.