1985: San Francisco Ballet is known as the oldest Ballet company in the country. In 1944, they produced the first American “Nutcracker”; the courtiers’ costumes were a deep red, made from old theater curtains because World War II had rationed fabrics. By the 1980s the company had fallen on hard times, about to go broke. But the dancers took to the streets and saved the day.

Still, moans arose when, after a glorious career with New York City Ballet, the Iceland-born Helgi Tómasson arrived as artistic director, almost a blank slate here except for his dancing. “No,” the word went around among dancers and audiences. “We don’t want and don’t need another Balanchine Company,” was the complaint—Balanchine had created roles specifically for Tómasson, such was his admiration.

“What people didn’t realize,’ Tómasson once told me, “is that Jerome Robbins was as much an influence on me as Mr. Balanchine.” After all, in 1969 it was a solo from Robbins’ “Dances at a Gathering” that won Tómasson the Silver Medal at the First International Ballet Competition in Moscow, only one step behind Mikhail Baryshnikov.

2022: Dancers and audiences are moaning again. After 37 years, Tómasson is retiring. (SF Ballet’s next artistic director will be Tamara Roja. So what has he done besides leaving San Francisco Ballet esteemed internationally and considered the second-best company in the country, with an endowment the envy of many large universities? Maybe his last season, undoubtedly prepared with special care, can offer a glance. Yes, there is both Balanchine (“Symphony in C” in program 1) and Robbins (“In the Night” in program 2). There are also two very traditional 19th century classics, with “Don Quixote” and “Swan Lake.” They fill the seats and the company’s coffers.

But for the rest of the six rep programs, Tómasson leaves a company clearly focused on the 21st century. Working with a centuries old dance tradition, expanding and stretching the vocabulary to meet contemporary sensibilities, he has come to firmly believe that Ballet has a future.This season’s six rep programs include five world premieres, and West Coast premieres by international greats William Forsythe and Alexander Ratmansky. Forsythe’s “Blake Works” dates from 2016; Ratmansky’s “The Seasons” from 2020. It’s difficult not to think of ballet as a 21st century art.

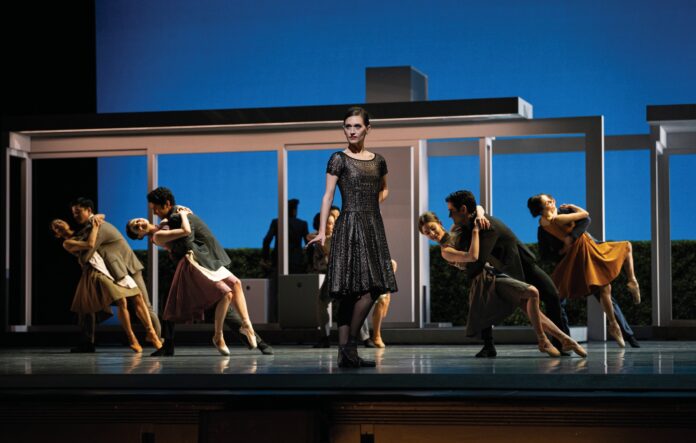

Maybe the season’s most anticipated world premiere was Cathy Marston’s “Mrs. Robinson”—performed in program 1 of the season (through February 12)—in part inspired by Charles Webb’s novel The Graduate and the famous movie with Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft. Those who expected steamy sex between Sarah Van Patten’s Mrs. Robinson and Joseph Walsh’s Benjamin might have been disappointed. There were plenty of intertwined bodies and limbs flying in all directions, but what kept the attention was the way the two of them were drawn to each other almost despite themselves.

Stumbling all over himself and not fitting in with his buddies, Walsh brilliantly set himself up to be drawn into the spider web of a suppressed Van Patten. When this frustrated wife and mother exploded into a volcanic fierceness, she became dangerous. Marston had set the ballet in the 1950s, when women’s lives were constricted by marriage and home-keeping. She had given these roles to a bevy of young women dancers who stalked around in lace aprons and pointe shoes. It certainly was an effective way of subversively ridiculing the much-maligned pointe shoe, itself often considered a relic.

But finally, when Walsh, being the good son to parents Tiit Helimets and Jennifer Stahl, ended up in the arms of Mrs. Robinson’s daughter–a beautifully dancing Madsion Keeler—I decided that I preferred the movie.

The season had opened with one of Tómasson’s own works, the 2011 “Trio” for three couples and a small corps, set to Tchaikovsky’s “Souvenir de Florence.” The work apparently got its name from the fact that the composer had written two of its movements in that Renaissance capital. “Trio” boasts of handsome but pale choreography. It’s three sections did not end up to a satisfying whole, despite Norika Matsuyama and soloist Cavan Conley quicksilvery first duet. It bubbled like champagne.

A darker note entered the second, most successful section when a languid Dores André gradually gets seduced away from her partner by an ominous Daniel Deivison-Olivera. For the finale Angelo Greco shone in his solos but his partnering with Misa Kuranaga’s folk-inspired variation lacked verisimilitude.

“Symphony in C” is the only Balanchine choreography in this season. Tómasson could not have chosen better even though the female corps deserved more rehearsal. Balanchine had set Bizet’s youthful score in 1947 at the Paris Opera Ballet. That was two years after the end of World War II. Paris was in ruin, people still starved. They were just barely beyond the time when the only way you could get a hot shower in the city was at the Opera Ballet. Such beauty, such elegance; such simplicity must have overwhelmed the audience.

The ballet is a wonder of clarity and geometry. Unison and canons, mirror images and solos, overlapping and sequential moves alternated and coincided. The steps are not that difficult but they demand utmost focus. The piece is visually a treat because of the complexity of design but also—what a simple idea—by the riveting effect of putting the women in white tutus and the men in black velvet. Sasha de Sola (with Aaron Robinson) was fast, precise and danced through the music.

There was such joyous power to her control. She looked the prima ballerina she could be if SFB had them. In the second movement’s adagio, Van Patten outdid herself, languidly finding her way, floating and rising and ending Ulrik Birkkjaer’s arms. Isabelle DeVivo and Walsh took on the third movement while Matsuyama and Hansuke Yamamoto gathered the “people” for a joyous finale.

SF BALLET’S PROGRAM 1 runs through February 12 at the War Memorial Opera House, SF. More info here.