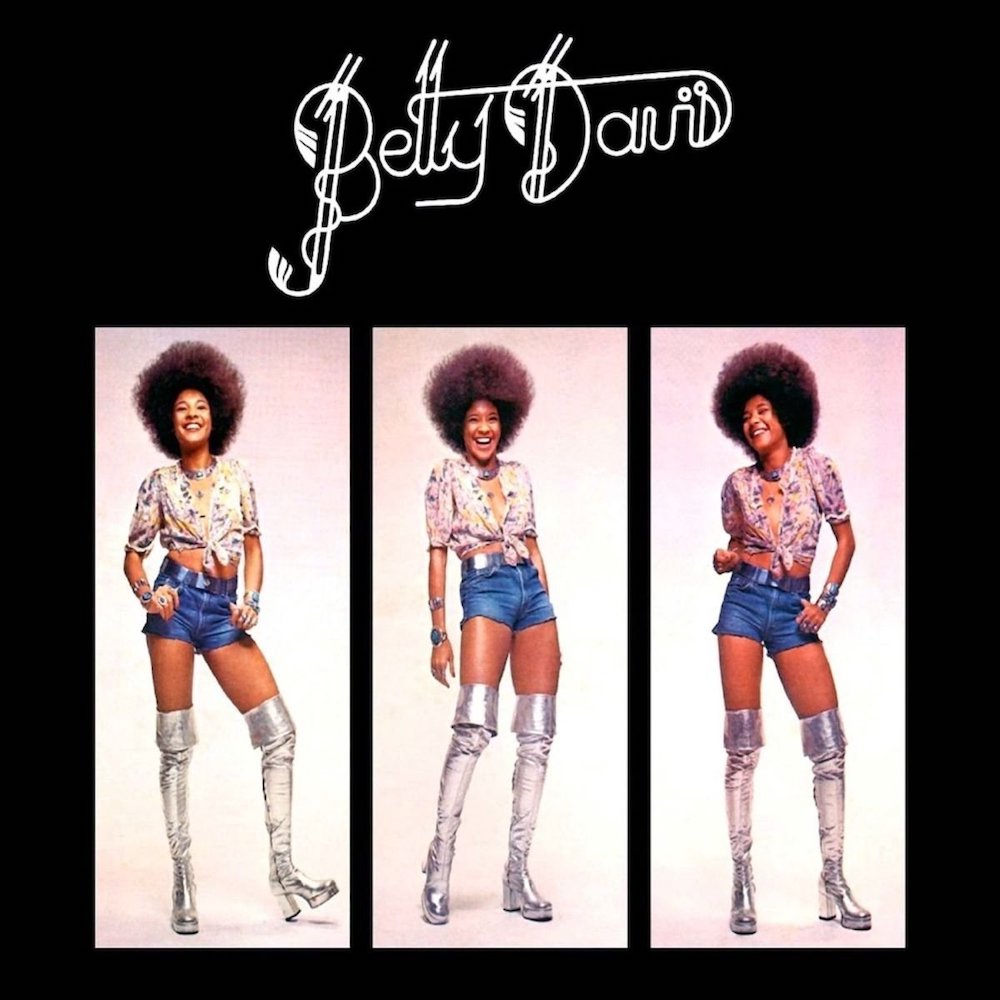

Betty Davis wrote, produced, sang, screamed, danced—and shook it in all the bad boy rock ’n’ roll ways of her times. She came up in the post-Civil Rights era, when Black performers were looking to introduce themselves in a presentable way (that’s code for making themselves safe for white financial consumption.) But Davis was an embodiment of women’s lib, Black power, ERA, and the counterculture. A friend of Jimi Hendrix and an avid fan of Marc Bolan of T. Rex, The Who, and Cream, she later would marry and divorce Miles Davis.

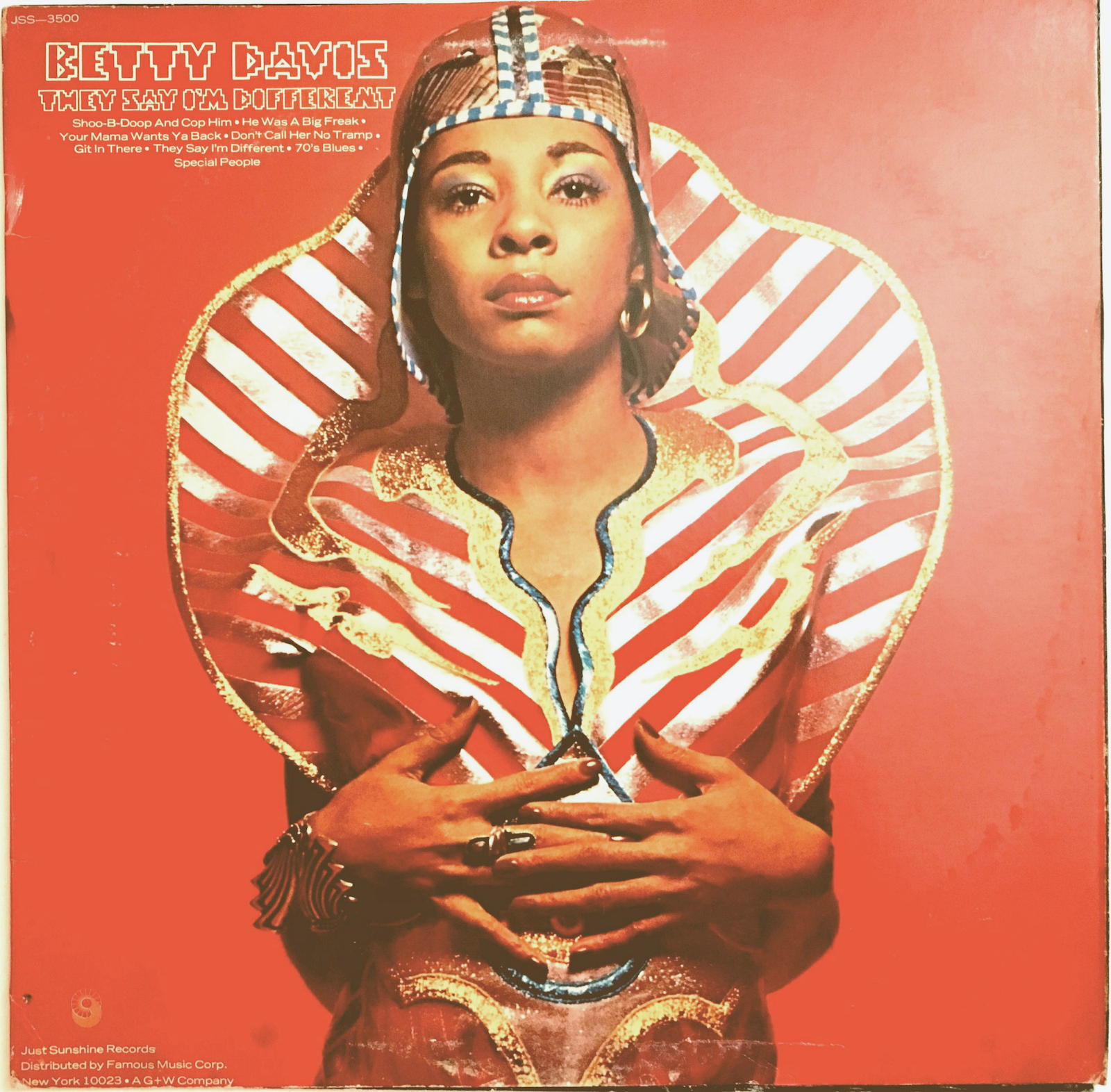

So imagine America catching wind of this tall, thick, sexually aggressive Black woman adorned with a full blow-out Afro, screaming at the top of her lungs: “He was a big freak, I used to beat him with a turquoise chain.” Her stage persona flew directly in the face of cultural norms attached to women and sexuality in general, a potent version of Mick Jagger and Rod Stewart sticking a cucumber in their pants (a precursor to the eggplant emoji, for sure.) Audiences—Black, white, anybody—were not ready to see that from a woman.

Especially from a Black Woman. The paradigm was being challenged, and it made folks in a position of power uncomfortable.

On their Betty Davis episode, hosts of Mike Judge’s Tales From the Tour Bus recall a live show that left attendees blown away by her daring. These weren’t the white record label executives who were constantly telling her how to be and perform in her own Black body. No, these were Black dudes, who paid full price to see her show, they were the ones getting vexed and falling out. Due to her overpowering appearance and execution, men were so stripped of their bearings they legs gave way to the pull of gravity. Now, that’s some shit right there. Supposedly Muhammad Ali once showed up at Davis’ dressing room door after a performance. We can only guess that “The Greatest” liked her show too. That’s power, Jack.

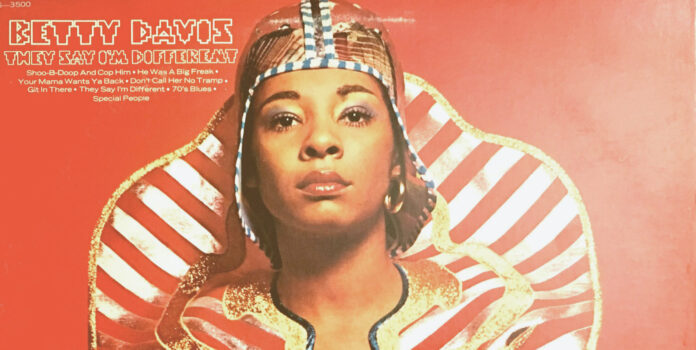

Betty Davis, born Betty Mabry, went to New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology and worked as a model before going on to become an awe-inspiring artist. After three years of unleashing potent creative output and three albums, she disappeared into private life for decades. Some say, it was her way of not succumbing to the limitations of her time. She passed last week at the age of 77.

Davis penned the song “Uptown” for The Chambers Brothers and wrote tunes that got the Commodores signed to Motown. Those are FACTS, as the kids say, not myths.

But for years, whenever talking about Betty in passing with other DJs in the Bay Area, it felt like a secret handshake society.

Before 2007, when the Seattle-based Light In The Attic Records put a great deal of her catalog back in circulation, Davis’ physical releases were difficult to come by. They had a certain mysticism about them. Tracking those LPs required scampering about every damn thrift store in Northern California, touching base with every Black-owned mom-and-pop record shop in the Western Addition and Lower Haight (remember those?), foraging through garage sales, haggling with apartment stoop hipsters and they dang pop-ups in The Mission, and of course, those always-successful lawn-clothing sales on Sundays in the Castro. Few of these trips panned out—even if they did, those joints did not come cheap.

I had a homeboy who worked for Jody and Michael McFadin, owners of San Francisco’s own Ubiquity Records, around 1995 or so. On the weekends I would roll with “the Homie” into the offices with a stack of blank cassette tapes, and spend six to eight hours just taping the rare, out-of-print records that the store clerks would have to “go in the back” to find. These were precious pieces, real expensive jawns, not trying to be advertised in case of theft.

On one such occasion, I came across Lightnin’ Rod’s Hustlers Convention, which featured uncredited music played for free by musicians like Kool & the Gang, Eric Gale, Bernard Purdie, and Billy Preston. I thought my dig for the day was over. Then I stumbled across that first self-titled Betty Davis album on the Just Sunshine label, recorded at San Francisco’s Wally Heider Studios, which would later become the fabled Hyde Street Studios between Turk and Eddy. Club 222 across the street (where I’ve DJ’ed) was once the Black Hawk Jazz Club, where a series of Miles Davis’s live sessions in the ’60s were recorded (In-Person Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk, volumes one and two).

I scanned the liner notes on the back and saw Davis’s players. Whew! Bay Area pedigree on showcase, straight flossin’. Produced by Greg Errico, drummer for Sly and the Family Stone, the record also featured contributions from guitarist Neal Schon (pre-Journey), Bay Area jazz musician Jules Broussard on baritone sax, future disco icon Sylvester, and members of Santana, Tower of Power, Graham Central Station, and Pointer Sisters. Not one bunk musician in the group. This was a top-flight outfit that Betty had no problem running.

In May 2007, Pitchfork said the record, “fused soul, sex, and hard rock like the best Sly or Funkadelic disc, albeit from a female perspective. But if George Clinton waved his freak flag proudly, Betty Davis wore it as underwear then rubbed your face in it.”

Quite accurate.

And yes, she was married to Miles Davis for a year. They started dating after she broke up with Hugh Masekela. She threw Miles’ dated Italian suits in the trash can and brought him a whole new culture bag, turning him on to rock, Sly Stone, and the fashion of the times. Eventually she was the tipping point in his musical vision for Bitches Brew. Originally it was named Witches Brew, but she suggested the name change, since Miles loved using the B-word. He even put her image on the cover of his Filles de Kilimanjaro album.

He also physically abused her. Hurt her. Which led to their divorce.

Even after, they stayed in touch, and he assisted Betty with putting together bands and arranging songs, even calling in the middle of the night for suggestions on chord changes.

But enough has been written about the Miles angle.

So many, including Betty, will say she was ahead of her time and such. That’s bullshit. Society, culture, and humanity would not allow her to call her own shots. Record labels and executives shut her down, which led to her disappearing for a significant amount of time and dealing with mental health issues. It wasn’t her confidence that failed her, it was the opposition that refused to let her perform in her way.

But when the next generation samples your work? Game over. That’s an indicator that the previous generation fucked up.

While researching this piece I came across a Betty joint I never heard before that is just ridiculously juicy: “Shut Off The Light,” from the Nasty Gal record. It should have been a standard, a foundational piece of funk of its era instead of a golden-nugget discovery 30-odd years after its release.

Betty deserved far better.