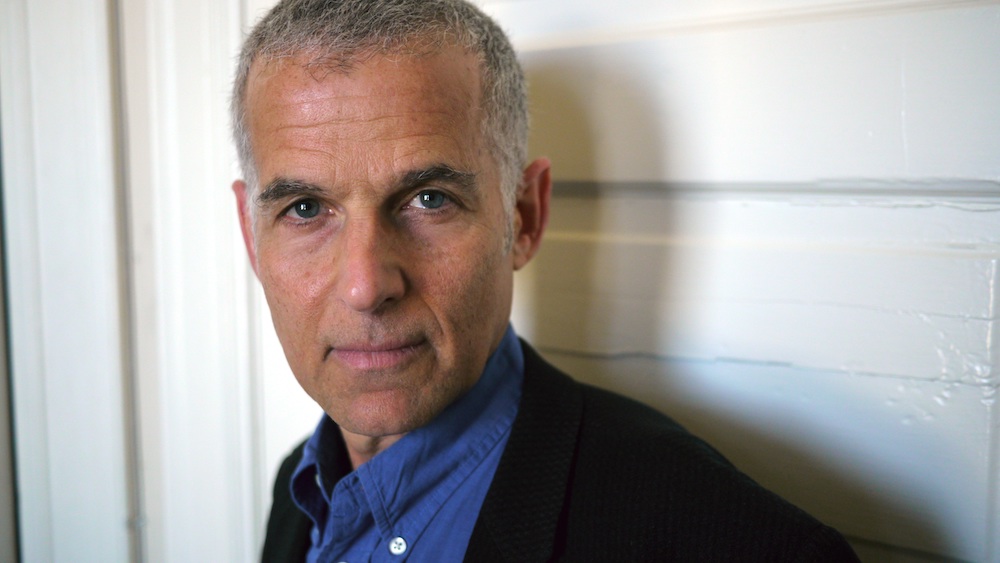

Jay Rosenblatt wonders if he would have any memory of the incident that forms the basis of his Oscar-nominated short documentary, When We Were Bullies, when he and his fifth-grade classmates, acting as kind of a pack, set upon one of their own if they hadn’t been caught.

“I blocked out a lot of stuff from that time in my life, because of this traumatic thing that happened in fourth grade, so I didn’t have as clear a memory as my classmates,” says the filmmaker and Jewish Film Institute Program Director. “We were kids. These things did happen all the time… We were caught and shamed by our teacher. That was seared in my memory. I felt so bad. I think, for the most part, we were all pretty good kids, so to be caught doing something we were ashamed about, that’s why I remembered it.”

When We Were Bullies is not the first time Rosenblatt has revisited the incident. That memory was the trigger for his 1994 documentary, The Smell of Burning Ants, in which he explored cruelty in boys and how boys are socialized. But in that film, that long ago afternoon was only a small part of a larger canvas.

Still, The Smell of Burning Ants planted the seeds for When We Were Bullies in unexpected ways. For one thing, it is the film that brought him back in touch with Richard Silberg, whom he hired to narrate the earlier film, the two of them only realizing later they were long ago fifth-grade classmates. It was a bit of serendipity that stayed with Rosenblatt and became a story he told often. Then more than two decades later he received an invitation that beckoned the San Francisco filmmaker back to his native New York to attend the 50th reunion of his fifth-grade class.

“I didn’t even know that was a thing,” Rosenblatt says. “I didn’t have contact with anybody from that far back. There was something beyond me saying I should go back and explore [what happened]. It was an incredible opportunity. Who knew where it would take us?”

With Silberg—who once more handles narrating duties, along with appearing in the film—joining him and camera in hand, Rosenblatt went to the event, quickly realizing filming there was impossible. It was too loud, and his classmates were excited to see each other again, trying to pull people out to interview them was not doable. But he also surprised himself.

“I actually enjoyed it,” he says. “I remember more from grade school than I do from middle school and high school. I remember my teachers better from grade school. A lot of the people that were there were familiar. Some of them looked completely different, some of them look unbelievably the same—same haircut, with wrinkles and things. There was something very pleasant about it. People were very friendly. I was really glad I went on that level, on a personal level.”

Later, mostly through phone calls, Rosenblatt rehashed the bully incident with his classmates, employing documentary, animation, and archival materials to build a kind of childhood Rashomon, each person remembering the incident differently.

“No one remembered it like Richard, my narrator, who I had already interviewed for the film,” Rosenblatt says. “He seemed to have the most detailed memory. I don’t know how perfectly accurate his was but there was something that got underlined. Let’s put it this way: When someone said something that I felt in my body, it kind of confirmed details I wasn’t quite sure of. When I heard them say it, I could usually feel it my body, it felt right. One person talked about us chanting. She even remembered what we were chanting. I don’t use that in the film because I didn’t want to identify who we bullied. But when she said that, it kind of brought me back.

“I was on both sides,” he adds. “In this incident, I was complicit. At best, I didn’t do anything. At worst, I participated in some form or another. But I was also bullied growing up, not incessantly, but I especially remember this one guy, he was a huge bully. We grew up in this apartment building complex. I’d be sitting on a bench, and he would just come over and start punching my arm really hard, and he’d just keep doing it.”

One thing that surprised Rosenblatt was how well his classmates remembered him and the sympathy they expressed for the loss he suffered in fourth grade when his brother died. He never talked about it and had no idea that they even knew, but their empathy 50 years later moved him and also contributed to When We Were Bullies.

“It became a key to this film, because it brought me back to that state of being and it really helped me make a connection to the person we bullied, through the vulnerability that I imagine he felt and the vulnerability that I was kind of hiding,” Rosenblatt says.

The Oscars are Sunday, March 27. “When We Were Bullies” starts airing on HBO and HBO Max on Wednesday, March 30, just the latest accolades for the film that started when it was accepted into the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. The Academy Award nomination is a first after decades of filmmaking—and lands the very year the powers that be decided to sideline the short documentary category (along with several others) from the live show, giving the award before the big ceremony and showing a taped segment.

“It’s a strange situation, Rosenblatt says. “I feel honored and privileged to be in this position but, that said, it’s unfortunate… Short filmmakers are already almost like second-class citizens in the film world, so it underscores that even more.

He adds, “It’s an amazing experience. It’s a recognition that feels very satisfying. I’ve been making films for a really long time. I’ve never had this level of recognition. I’ve never been this busy in my life.”