There’s only one more season left until “Stranger Things” is over, but fans shouldn’t get too down just yet. The series’ creators, the Duffer brothers, announced their new production company Upside Down Pictures will be bringing a spinoff to Netflix that expands upon the series’ world even further—with entirely new characters.

Such is the result of four seasons of a show that has become so popular that it’s inspired merchandising from Quicksilver, Timex, Monopoly, Jansport, and even Lite-Brite, the latter of whom dug into their ‘80s archives to revitalize some retro looks.

But what of the show’s most recent run?

Its soundtrack has always run high on the nostalgia factor, but never before season four has it so successfully employed a track like it has Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill,” a revival from which the singer made approximately $2.3 million. Since May, the song has broken three Guinness Book of World Records and topped several charts.

Bush got as excited about the series as hardcore fans.

“I’ve just watched the last two episodes of ‘Stranger Things’ and they’re just through the roof,” she wrote on her website. “No spoilers here, I promise … now having seen the whole of this last series, I feel deeply honored that the song was chosen to become a part of [the Duffer brothers’] roller-coaster journey. I can’t imagine the amount of hard work that’s gone into making something on this scale. I am in awe.”

Season four of “Stranger Things” continues the Netflix series’ tradition of drawing influence from classic literature. Plus: good versus evil. Moral ambiguity. The hero’s journey. Star-crossed lovers. Dramatic irony. Chekhov’s gun. Drug dealers. Jackass jocks. Rednecks. Cults. Serial killers. “Evil” Russians. Dating woes. High school cliques. Rebels. Outcasts. (Super)heroes. Monsters. And that pesky alternate dimension, the Upside Down, that just won’t leave the series’ small suburban town of Hawkins alone.

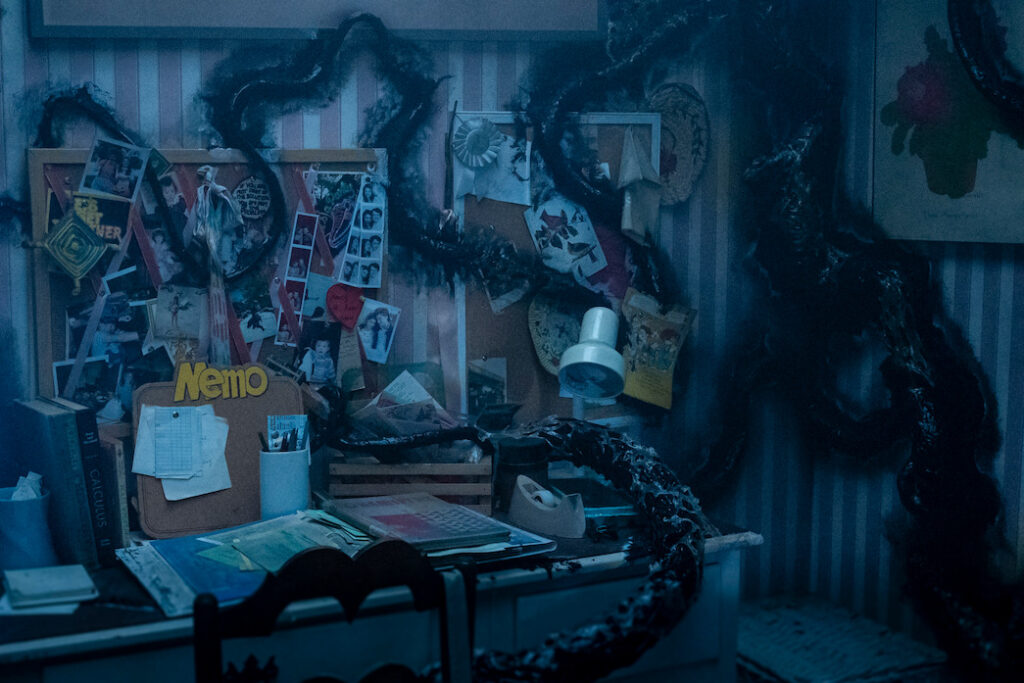

Speaking of influence, whereas previous seasons of “Stranger Things” embraced unabashed Spielberg-ian admiration, season four leans more heavily into Carpenter and Cronenberg influences via its body horror, existential dread, and suburban commentary. The town’s disgust for Hawkins High School’s Dungeons and Dragons-playing Hellfire Club, for example, is a clear skewering of 1980s politics. The burb’s mistrust of the club full of misfits summons that decade’s “Satanic panic,” a Reagan-era backlash to punk, drugs, new music, sex, and progressive. The Hellfire Club presents a perfect distraction from the real villain of “Stranger Things”: Vecna, the ultimate manifestation of the ominous Upside Down.

The series’ now-beloved characters attempt to shield Hawkins from this other dimension and its mastermind, The Mind Flayer. This amorphous wretch prays upon the vulnerable, the scarred, the repentant, the dejected, the compunctious. At its helm lies 001, an ideal host for such evil, the only one thought to be as powerful as the series’ once-psychokinetic, Eggo-loving protagonist Eleven. 001 is a wayward soul confident in his ideology. So much so, that he’s willing to senselessly slaughter to prove he’s—well, number 001.

“Stranger Things” eventually reveals that the Upside Down is the physical manifestation of the trauma America inflicts abroad on a daily basis, backfired. Genocide, non-combatant massacres—all for the sake of “freedom.” Here is everything we’ve brushed under the rug, bursting at the seams, exploding back in our faces. And what better backdrop against which to set the Upside Down than the Cold War, present in the series from its very start?

Only in the show’s telling, instead of a space or nuclear arms race, America and Russia use the Upside Down’s creatures to try and get a leg up against each other. Here, the Russians experiment on the realm’s murderous, bipedal Demogorgon—and the US, on children like Eleven.

The show was originally titled Montauk, a nod to the Montauk Experiment conspiracy theory. Believers hold that the US government experimented on homeless people and kids to sharpen their telekinetic and preternatural abilities. Montauk Experiment theorists hold that in so doing, the government opened an interdimensional portal and made contact with a monstrous being. Sound familiar?

“This evil, it’s like a virus,” one character proclaims in season four. Might the saying sum up the United States’ destruction abroad, and its treatment of oppressed groups at home?

To quote Zizek, “It is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism.”

And then: “It might not work out for us this time,” says a character in volume two (as is called the second half of the show’s season four—which proved to be so long, the Duffer brothers split it in two parts.)

What if, then, there is no clean end in the next season? What if the Upside Down wins? Will America get—what it deserves?

Forget America first—”Stranger Things” is about America last. The failed ideology of capitalism is evident amidst the decaying suburbs of Hawkins, where enlightened citizens are the world’s unlikely saviors in spite of government stooges’ intervention.

This is not a tale of a few bad apples but rather, a pest-infested apple tree, from which only a select group of strange fruit have the privilege of falling as far from the diseased trunk as possible.

The Duffer brothers build upon pairings that worked well last season amidst the show’s secondary cast.

Private investigator Murray and bereaved mom Joyce are anxiety-ridden, paranoid, and yearning for something: a platonic match made in heaven. Joyce has faced as much loss as any character in the series: her abusive husband, a kid to the Upside Down (if temporarily), her once-idyllic nuclear family. Murray longs for an adventure, to prove himself. As Joyce says in volume two, “He’s the Starsky to my Hutch.”

Robin and Steve’s relationship is, without a doubt, the sweetest friendship in the series. An in-the-closet lesbian motormouth and a slacker ladies’ man with a soft heart, both desperate for love. What could go wrong?

Oddball, rebellious Steve’s character arc is one of the most drastic and satisfying, as is the development of the outcasts, the dreamers, the conspiracy theorists, and the damaged who see through the American daydream on “Stranger Things.” They are the ones who prevail, who fight against the ungodly forces that America has created.

That’s why it’s no surprise when newcomer Eddie (played to perfection by Joseph Quinn), the perpetual senior and unusually-kind drug dealer, steals the show. Immensely-relatable and infectiously-lovable, his dramatic plot arc is nothing short of spectacular. Eddie represents the unwilling fallen soldier, drafted to fight a war that doesn’t belong to him and that he doesn’t understand. He is every soldier lost in Afghanistan, Iraq, Vietnam.

Volume one sets up the conflict with a series of mini-mysteries that propel the narrative for volume two, in which the final showdown between 001-Vecna and El takes center stage. Volume two gives us two full-length movies: shades of a pre-Upside Down tranquility shine through, until the massive storm breaks that is episode nine’s two hour, 22 minutes, and six seconds runtime. Yes, you get to hear “Running Up That Hill.”

In volume two, the Duffer brothers expand the scope of the alternate dimension to fascinating effect. The finale is so spectacular that it changes the fabric of the show, setting it on an entirely new trajectory. It’s some of the best nearly-four hours of TV ever produced.

In one of the best scenes in the series, an Upside Down guitar solo to Metallica’s “Master of Puppets” blows the roof off. Hawkins is now under Vecna’s spell, rapidly transforming into the Upside Down. Robin may just be right.