Were I the type to believe in the supernatural, I might think my trip to Jonathan Carver Moore’s gallery was fate. I showed up to the Market Street site one week after the US Supreme Court decided that university students should live forever in debt, that university admissions could be as whitewashed as country clubs, and that everyone can discriminate against queer people because of a queer couple that didn’t even exist.

So, for a Black bi journalist, the opportunity to catch an art exhibit by Black queer artists felt like both a personal obligation and a chance to explore a safe space in world decreasingly safe for someone like me. And, given that the exhibit’s title of Sanibonani (through August 5 at the Jonathan Carver Moore gallery in SF) is Zulu greeting akin to “Hello,” it seemed like the perfect place to find that safety.

Curated by South African artist Zanele Muholi, the exhibit is a continuation of their work exploring race and sexuality. Specifically, the artist (whose work will be featured at SF MOMA this coming February) compiled the works of a handful of young South African photographers—all Black and queer—under the theme of simultaneously being seen and not.

Granted, even without the intimacy of Moore’s gallery, it’s hard to miss the one non-photo piece: a large bronze torso self-image (Muholi III) of a cross-armed Muholi with long feminine braids (possibly dreads), a wide-brimmed hat over their expressionless face, and wearing what-appears-to-be a tuxedo and bowtie. Moore says bronze is a relatively new medium for the artist, but it doesn’t show.

It’s a striking piece relating to their overall work, but more on-theme are their self-portrait photos on the walls. The standout image features Muholi against a black backdrop with only their eyes (and a faint light reflection on their face) visible from the shadows. Indeed, simultaneously seen and unseen.

As he walked me through each piece, Moore told me how violence, unfortunately, informed a considerable amount of the 18 photos on display. This was particularly true of Nkosi Ngiphile’s monochrome Yithilaba, featuring the artist and an unnamed best friend sitting back-to-back in a bathtub, their heads resting on each other’s shoulders and their dark complexions contrasting against the bright tilework. The photo, as Moore explained, was taken in the aftermath of Ngiphile being the victim of a homophobic attack and wanting to create a true welcoming environment with someone who really cares.

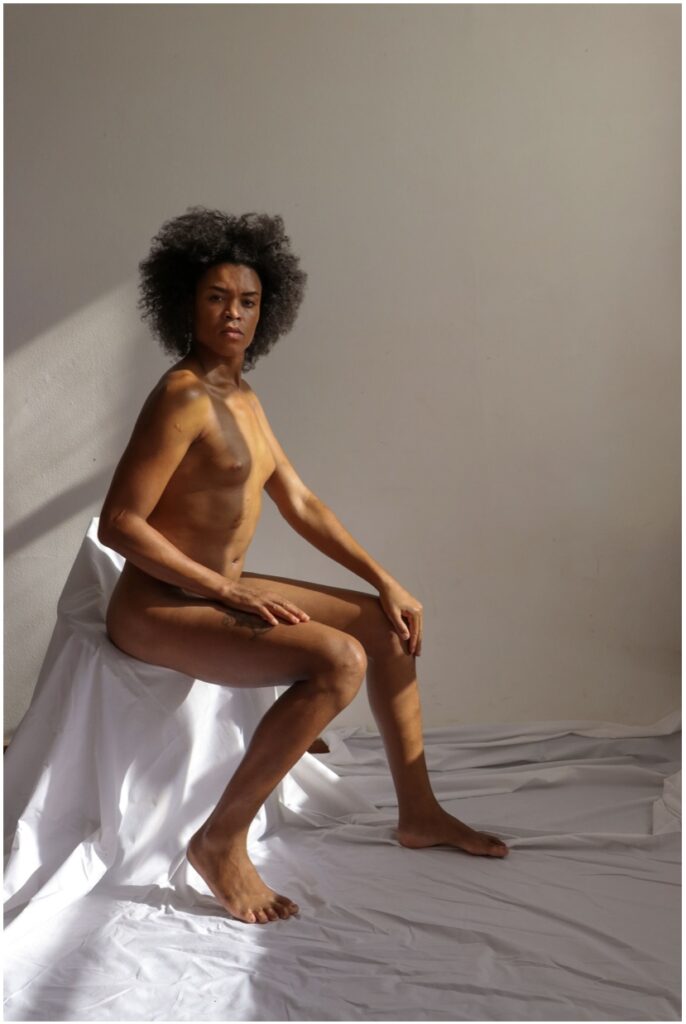

Similarly, trans beauty queen Mellisa Mbambo took the full-color nude self-portrait Identity 2 shortly after having been mugged. You’d never know that from the photo, featuring someone clearly at ease in their own in skin, which is touched by the sun coming through an unseen window.

As visceral as that pain (and comfort) can be knowing the backstory, Ngiphile’s photos actually feel complimentary to those of Lulu Mhlana, whose monochromes Nolu (ii) and Ntshware ka letsoho feature the artist in bed with her partner as a way normalize the comfort and security of Black intimacy. A third photo, Uthando Lwendoda, was particularly favored by Moore as its image of two smiling Black men in bed remains a far-too-rare sight in mainstream media.

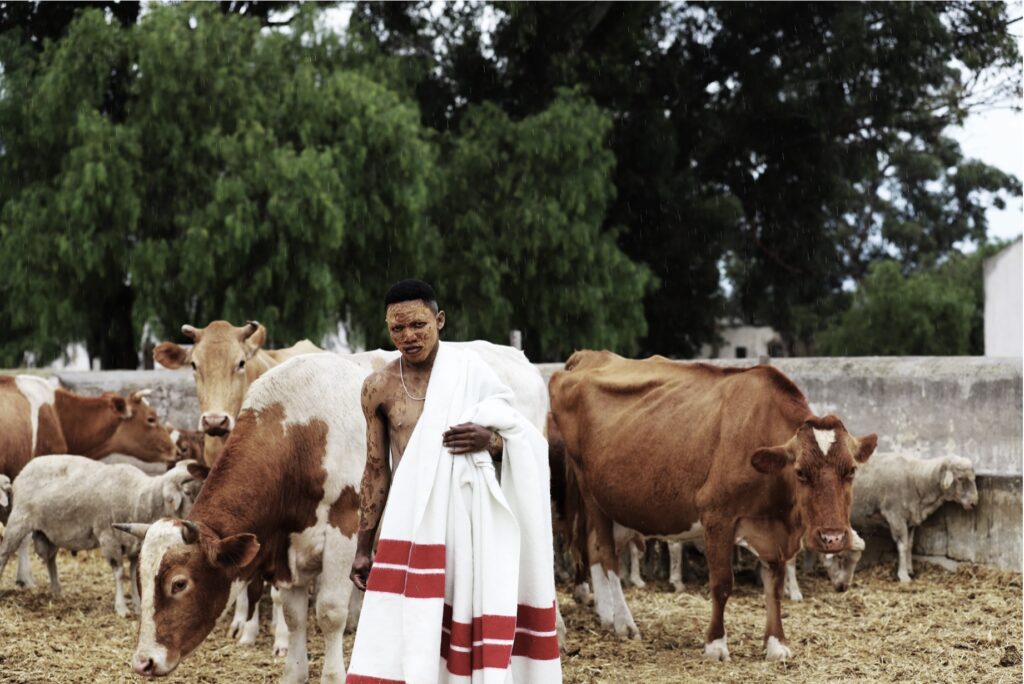

Rites of passage also come up in at least half of the photos on display. Sipho Nuse’s full-color shots (which really stand out amongst all the monochrome) feature the photographer belatedly taking part in the ritual in which young men are circumcised, sent out into the woods to fend for themselves, and expected to come back as fully matured. Nuse’s participation was put off because his queerness was seen first as hindrance to the rite, then the rite itself was later seen as a potential “cure” for said queerness. Post-rite, Nuse is seen with his face covered in dried mud, wearing a large fabric of pure white (representing, Moore tells me, both purity and the end of childhood) with red accentuation (representing the blood of the circumcision).

Finally, there are the four photos of Collen Mfazwe documenting the journey transitioning. The first, Abalele, is a close-up of the photographer’s pre-transition passport, which is paired with a self-portrait, Isazisi, of a bearded Mfazwe now. This leads to the one photo that may best encompass all the installation’s themes—being (un)seen, rites of passage, safe space, lasting scars—all at once. It features a post-op trans man lying naked on a bed in comfort, his arm behind his head, making his top-surgery chest scars impossible to miss.

Given all that’s happened in the US lately, I couldn’t help but ask Moore if Muholi or the other photographers had expressed any specific opinions about having their work on display in such a prominent American city. He told me that he did ask, but they’re so dedicated to documenting and making safe spaces for their fellow Black queer Africans that the goings-on here are a distant thought, at best.

That lingered with me after I left. Not in the sense that what’s happening here is trivial, but in the sense that the same struggle to be seen, heard, and understood is going on just as strongly here as it is in other parts of the world. (Hell, France has rioted for weeks because a teenage PoC was murdered by cops—a story we know all too well in the US.) Muholi’s small collection is easy to absorb quickly in Moore’s compact gallery, but that works to its benefit: For an exhibit about wanting to be seen, what better place than one where you can easily see everything at once?

SONIBONANI runs through August 5 at the Jonathan Carver Moore gallery in SF. Further info here.