These days, young people may only know of Fracis Ford Coppola as “that creepy old man who goes on ‘anti-woke’ rants and made that movie (Megalopolis) everybody thinks is ridiculous.” That wasn’t always the case. He used to be one of most revered artists in modern history, with great insights about his craft, the passion of his work, the pitfalls of searching for funding. I remember him on Inside the Actors Studio, telling the students that if they ever wanted to know who rules the world at any given time to just look and see who’s hiring all the artists—it used to be the Vatican, he told them, and today it’s corporations.

Though I’d be hesitant to associate with Coppola now, I can imagine he might actually like Gary Graves’ The Contest (world premiere through November 17 at the Berkeley City Club). With its themes exploring the intersection of arts funding and artistic inspiration, coupled with its Italian setting, it explores territory similar to Coppola’s current self-financed film. Mercifully, Graves (who also directed) chose to fill his play with compelling character work rather than the bells and whistles afforded by a vineyard fortune.

Though you wouldn’t know it from the play’s modern accouterments—contemporary dress and the use of a slide projector—but it’s meant to take place in 1504 Florence. The revered and flamboyant Leonardo da Vinci (Christopher Herold) has been summoned to the Palazzo della Signoria by his friend Niccoló Machiavelli (Alan Coyne), who represents the ruling government. The two begin arguing, mainly about the overflow of the storm-ravaged canals, which da Vinci designed but claims his specifications weren’t followed, before the playwright and government lackey offers his friend a job: paint a giant fresco in the Salone dei Cinquecento depicting the “victory” at Anghiari.

It turns the artist’s stomach to accept state money for such a transparent propaganda piece, but he finds himself in the artist’s eternal plight: He needs money. He vows not to shy away from the horror of war, but he reluctantly agrees. After all, it can’t be any worse than that statue of the naked guy in the Signoria’s courtyard, could it?

Speaking of which: Machiavelli being Machiavelli, he sneaks into a bathhouse to meet with the sculptor Michelangelo (Nathaniel Andalis). The kid is brash, arrogant, unrefined, possibly queer, and yet another artist in need of money. So, when the government stooge comes with an offer to paint the opposite Cinquecento wall, Michelangelo accepts—despite not being a painter by any estimation. Thinking himself apolitical, the upstart intends for his depiction of the Battle of Cascina to be an eye-capturing masterpiece of form and skill.

With that, the two artists are unknowingly put in competition with one another to create frescoes that will literally be face-to-face when completed. As da Vinci makes both great strides and many outlandish demands (plants, a lavish clothing allowance, at least one wall knocked down—the usual), Michelangelo struggles to make his first stroke of the brush. All the while, Machiavelli is the one who has to answer for whatever work the artists do or don’t complete.

Even if I hadn’t personally spent this year wondering how much I’m willing to compromise just to stay fed and sheltered, a question I’m forced to ask myself at this very moment, The Contest would still resonate as a compelling drama about the intersection of art and commerce. The fact that artists continue to be forced to make that choice is a failure of society, which here is shown as nothing new. Graves’ play—contrasting da Vinci’s outlandish demands with his sobering reality of the world, and Michelangelo’s dogged individualism with the realization that he’s lost on his own—holds fast to the belief that the artist is just as crucial to the creation and function of society as any engineer or politician.

After all, the two are made their offers by Machiavelli, an artist in his own right. Competition is healthy to keep an artist on their toes, and two masters competing is always intriguing, but choosing whether to bend to someone’s will or go with necessities is a choice that continues to haunt us.

Though Graves does a great deal with the minimalism of his production, the two central performances never completely strike the right note. Herold’s da Vinci (adorned in Tammy Berlin’s brightest colors, including a gold paisley sport coat) is the better of the two, as he does well at tapping into da Vinci’s sense of insult at not getting his way. Yet, Herold never seems to fully touch upon the sadness da Vinci feels at all the missed potential he observes.

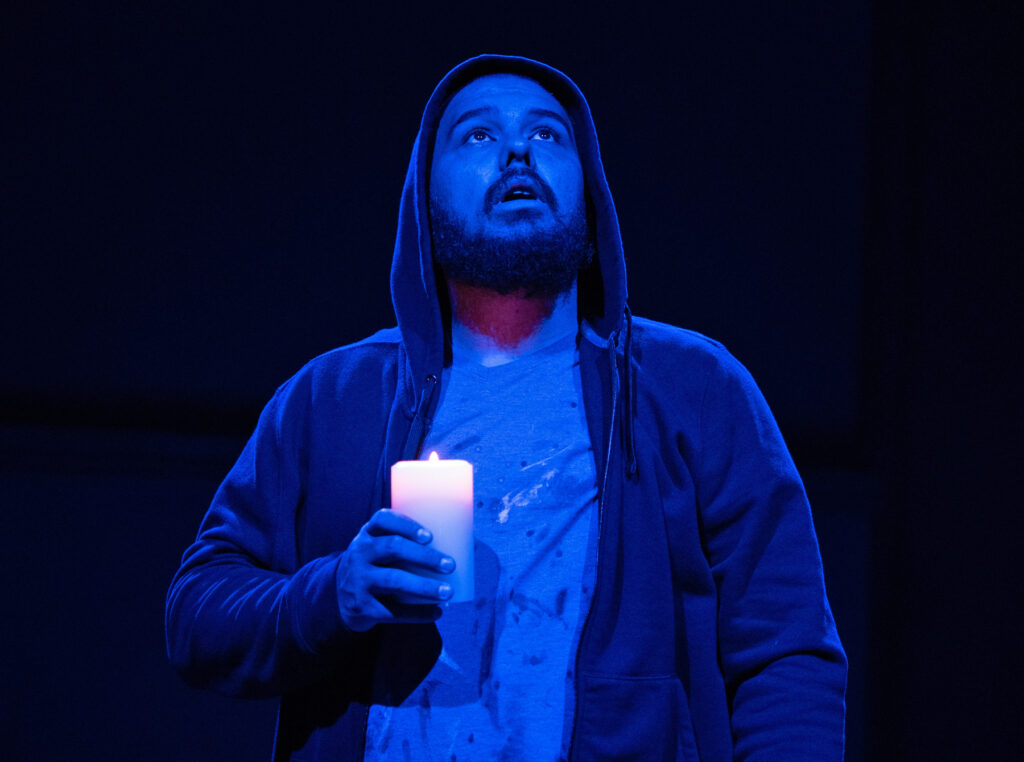

Andalis’ Michelangelo does better at touching that sadness, particularly in a scene where he begs God to help him create his work before his deadline is up. Where Andalis falters is with Michelangelo’s aggression, frequently growling his lines and coming off more like someone’s idea of toughness rather than an actual threat. Best served is Central Works regular Alan Coyne. He consistently finds the right notes for Machiavelli’s arrogance without losing his humanity. It’s a captivating performance during the entire show.

Central Works continues to be one of the few theatre companies still dedicated to a transparent COVID safety policy, for which we should all be grateful. The matinee in which I saw the show required masks, but a group of four seemed put upon by the requirement. Three of them deliberately wore their masks under their noses the entire show, and one woman in the group never put on her mask at all. Fortunately for the rest of us, there was enough ventilation in the performance area to enable safe airflow. As such, the CO² readings on my Aranet4 only peaked at 921ppm during the 75-min. show, dropping back down to 723ppm by the final bow.

After that bow, the post-show curtain speech implored for donations by noting the recent closure announcement from Cal Shakes as further proof of the dire state of art and non-profit funding. Indeed, more people and orgs are now competing for larger slices of a smaller pie with no clear signs of a solution. Like the artists of Graves’ play, we artists, journalist, and creators find ourselves literally devalued in a money-loving society. Though the answer as to how to change that remains murky (voting for candidates who support proper funding helps), The Contest delivers a compelling and all-too-relatable take on the real value art carries.

THE CONTEST’s world premiere runs through November 17 at the Berkeley City Club. Tickets and further info here.