In the middle of our press preview tour, we were led to an installation dedicated to the Moms 4 Housing protest. It includes a mock-up exterior of the house that was occupied by Dominique Walker and her comrades in 2019. Walker was one of the homeless Oaklanders offended by the house in question going unoccupied as she and her companions had no roofs over their heads. They occupied the house themselves, drawing national focus to both the Bay Area and the US’ housing crisis and wealth disparity. Five years after successfully claiming the West Oakland home, Walker’s most prominent contribution to the exhibit isn’t the mock-up of the house, but rather the video of her infant son taking his first steps within it.

This is the keystone installation of Black Spaces: Reclaim & Remain (through March 1, 2026 at the Oakland Museum of California). It doesn’t explicitly tell the story of the event that inspired the exhibit, nor does it explicitly state the lofty intentions of the architects and social planners who take part in the exhibit’s latter half. Yet, one could argue that no other installation so perfectly encapsulates “remain and reclaim” as the Moms 4 Housing display. In this solitary sequence (the mock-up of the house stands in the middle of the room, as if detached from the museum itself), not only do we see the result of the infamous redlining practices that gentrified the Bay Area, but also a visual reassurance that lost spaces can be recovered and rejuvenated.

One could also argue that it’s fate to open this exhibit days before its catalyst got its own public recognition and rejuvenation. As we’re told before the tour, it was 2022 when OMCA Executive Director Lori Fogarty was accepting an award in Washington DC. That’s where she happened to learn of Russell City, a prominent, primarily Black and Latine neighborhood of Hayward. In the 1960s, the aforementioned redlining saw the area razed and its residents displaced (not unlike the “Black Wall Street” of North Carolina). After learning of the incident, Fogarty spent the last three years trying to make a space for it at OMCA. By pure serendipity, the opening of the exhibit coincided with official calls for reparations for Russell City descendants.

Now, under the curation of OMCA’s Dania Talley, the museum hopes to enlighten visitors on what Oakland and surrounding areas were, remind them of what the areas currently are, and offer hope as to what they could be.

The exhibit is divided into four sections, the first of which is “Homeplace.” As its name suggests, the area is sparsely-decorated with gifted pieces of home staples, including a fireplace dating back to the late 1800s and a leather suitcase from the 1940s. The suitcase belonged to Otis Williams, born in Louisiana before heading to Marin during The Great Migration. We’re told he worked the shipyards of Sausalito and actively helped push Marin to becoming a more diverse residential area (something that seems hard to believe even today). Most prominent in the area is a lime-green sofa with a tweed rug at its feet, giving one a prime seating place to view the home movies of Earnest Bean (1940s). None of these items are particularly special, but all are comfortable.

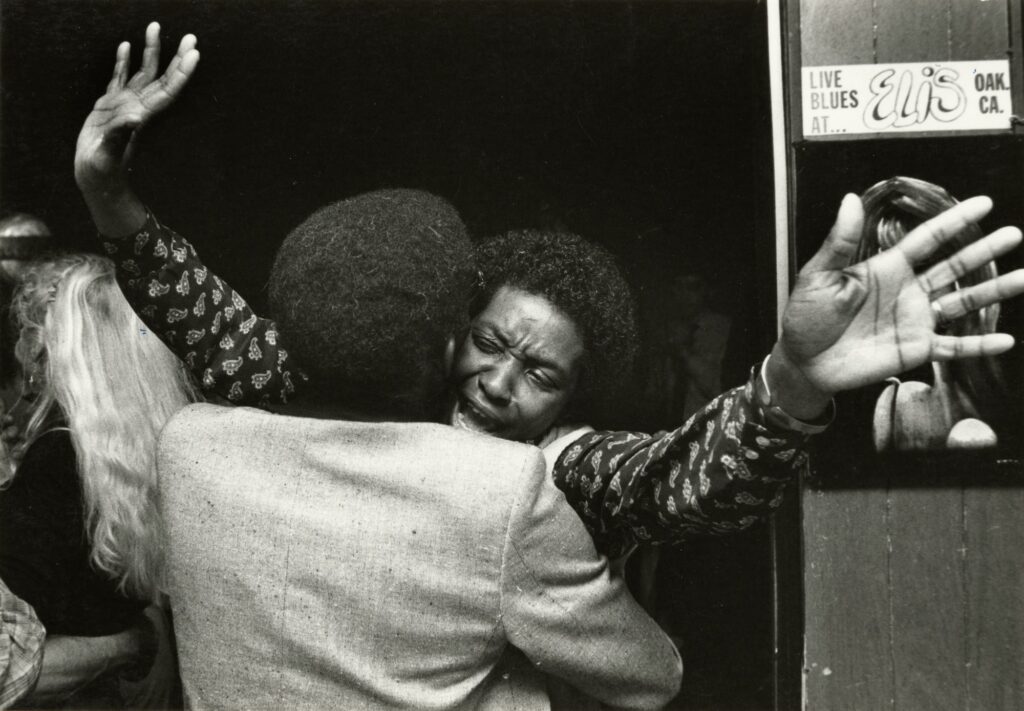

The second section is “Social Fabric,” emphasizing the areas Black residents built for themselves after gaining a residential foothold: churches; local businesses; entertainment venues. Outside of the workplace, these areas where Black folks were guaranteed to congregate together with little need for stress. At least, at first. As pleasant as this section is with its church programs and photos (by Joanne Leonard, Ruth Marion Baruch, and others), it also signals a tide-change with the mailbox of the Leonard Ancona family from the 1940s. You can’t miss it: It’s the tin box riddled with bullet holes. It sits in front of an aerial photo of Russell City and next to a map of the area. It evokes the feeling of a military plane identifying its target.

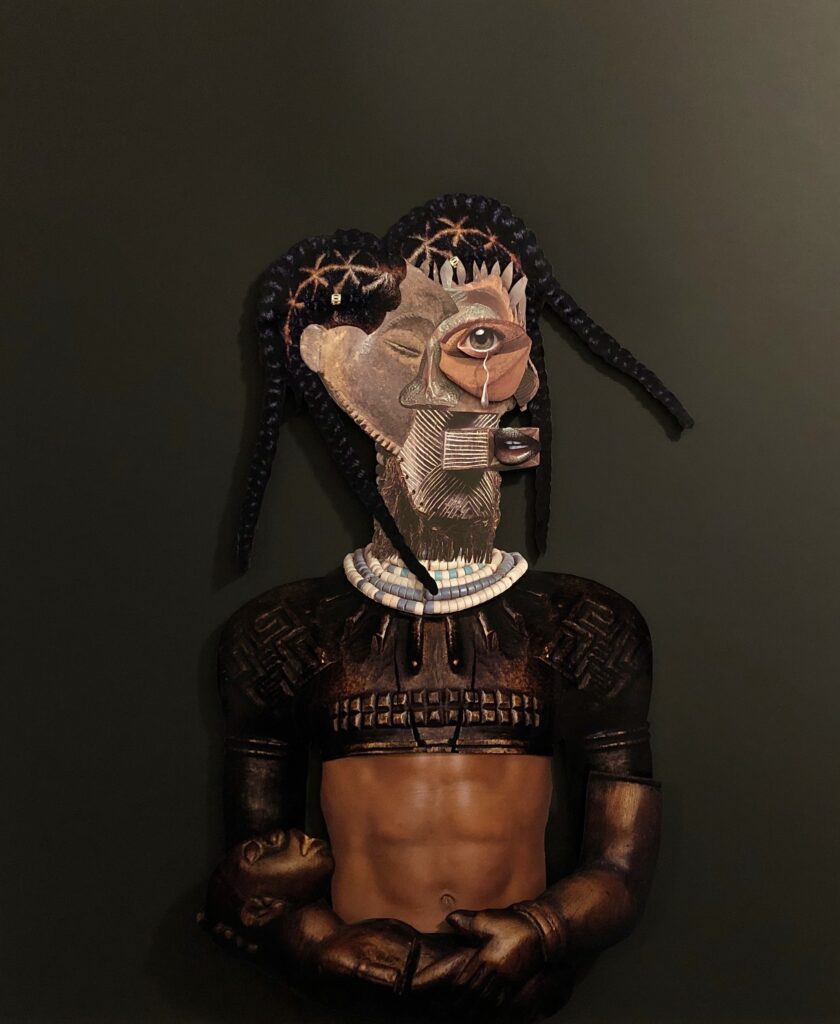

Hence, the next area is “Dispossession and Repair,” in which the 1949 Housing Act goes into effect and the Black Bay Area residents—particularly, those of Russell City—feel the impact head-on. This is an area full of protest signs and broken dreams. It where we find Oakland-born Adrian Burrell’s Electric Slide (2025), a metal tree made of bottles, lights, and television sets. They play video of the artist and his family in an almost Yoruba-esque ritual singing 20th century Black music. As Burrell himself states, the ritual was taking the pain and lessons from previous imperial attacks (like in ’49) and being prepared for them spiritually when they occur again (as they often do today). This entire section could have been called “rolling with the punches” in the way it suggests that the pain gentrification has caused merely strengthened successive generations with the fortitude to face it directly.

No wonder this is the section where one finds the Moms 4 Housing installation.

The fourth and final area is dedicated to architect June Grant of blinkLAB. It’s chockful of conceptual wooden models, Afrofuturist designs (a bit cringe-inducing with their blatant use of AI), and an overall concept known as “Russell City Re-Imagined.” It’s the sort of design one would see in a news report about a proposal for a new local park: clean streets, smiling faces, greenery in every direction. The difference is that this concept, as explained by Grant herself, is imagined as “what Russell City could have been,” had it not been razed by greedy, racist developers. It’s a rebuke to the colonial concept that justifies historical atrocities with “But look what good things came out of it!” Grant and her colleagues make clear that the late Russell City did fine on its own, could have done even better, and–with the proposed reparations and community control–could do fine again.

It’s a bold declaration that the oppressed don’t need a savior, they need control of their own destiny.

There was a pretty large crowd for the preview. Not many were masked, but the wide spaces and strong HVAC of the OMCA meant that CO² readings on my Arane4 never went any higher than about 489ppm.

I wasn’t able to stay for the post-tour grand reception, but something special happened on my way out. By happenstance, I passed by Dominique Walker and her children, including the same little one whose first steps make up the video in the faux house in the Moms 4 Housing installation. It was almost like a scripted bookending to the tour, with the exhibit reminding us of the great loss of Russell City, yet Walker and her family serving as living examples of what could lie ahead.

Both left their mark in just the right way.

BLACK SPACES: RECLAIM & REMAIN will be on display through March 1, 2026 in the Great Hall area of the Oakland Museum of California. Tickets and further info here.

![Brooke Anderson, Untitled [Moms 4 Housing Protest], Sept 1, 2020. Reproduction courtesy of Brooke Anderson and Moms 4 Housing](https://48hills.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Brooke-Anderson-Untitled-Moms-4-Housing-Protest-Sept-1-2020.-Reproduction-courtesy-of-Brooke-Anderson-and-Moms-4-Housing-696x469.jpg)