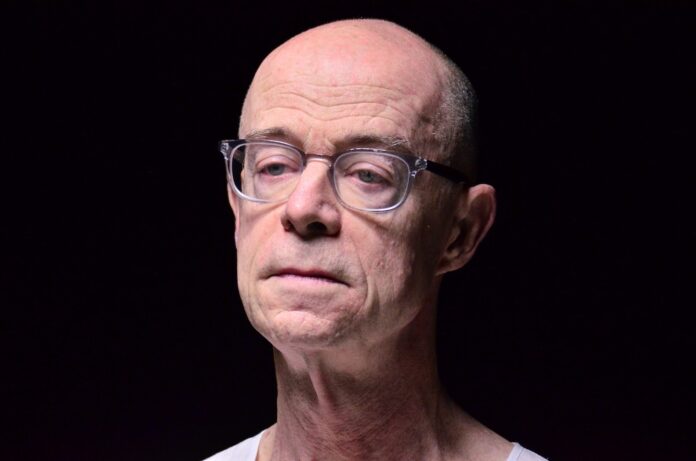

John R. Killacky defies category: Dancer, artist, writer, filmmaker, arts administrator and consultant, lecturer, grant panelist, former managing director of two heralded post-modern dance companies, victorious mover after a life-threatening surgical accident, an equestrian aficionado—and now a politician serving the people of his state in the Vermont House of Representatives. So why wouldn’t his latest book, Because Art (Onion River Press), also bound beyond expectations?

The slim edition sports a jet black and hot pink cover. Inside are essays that include a requiem for thousands of lives lost to the AIDS epidemic and a valentine to artists whose devotion to craft transcends spiritual practice and results in endeavors that are far more than simple pursuit of a profession. The book serves an astute guidebook for anyone presenting, producing, practicing, or studying art. It is also a memoir, in which Killacky’s life stories tumble like an avalanche in reverse to form a mountain not of boulders, but of boldness.

Bay Area and 48hills readers will make special note of the many references to the region found in essays relating to Killacky’s stint as executive director of Yerba Buena Center of the Arts and subsequently, program officer for arts and culture at the San Francisco Foundation.

Killacky divides Because Art into three segments—commentary, critique, and conversation—that as I read them, seemed more like three movements in a classical music cantata than a text-only body of work. His voice rings out with much different tone and language when dissecting types of artists-researchers—“discoverers and innovators” the field must “maximize” by mirroring corporate investment models—than it does when recounting the death at age 32 of Iranian-born director and playwright Reza Abdoh (who penned The Law of Remains and others.)

“Certainly, with all the practice, you would think loss and grief would not be so painful,” he writes, keening on the page after having lost another friend and artist who he admired as “our generation’s Artraud.” Our mourning of—or indifference to—a young life and artistic voice cut short, he points out, reveals more about ourselves than about the deceased.

Each titled essay comes labelled with a date: the year in which it was originally written. These are not a small details to ignore. Instead, the chronological documentation provides fascinating sub-context to the conversations, critiques, and commentary. In more than one instance, the date proves Killacky to be (to skew the overused, meaningless phrase, “a person with ideas whose time have come”), a person whose timely ideas have been presented repeatedly. But are the people who can enact change really listening?

“Survival Strategies for the Arts,” written in May 2009 for Blue Avocado, is one of the more obvious examples. In it, Killacky lays out his ideas for practices that arts organizations and audiences can apply to survive during periods of significant challenge. (When, I dare to ask, is challenge not the condition under which artists survive?) Notably, most of the artists about whom he writes fantastically not only survive, but pay taxes, boost the local economy, feed themselves and their families, enrich their communities, call for social justice and civil rights, meld and heal and make whole divided people across geographic boundaries, and move hearts or transform lives as they offer anyone willing to pay attention hope and evidence that life is more than only commerce.

To emphasize the finer point of timeliness, most of Killacky’s strategies in this “Survival” essay that likely were prescient in 2009 appear no less applicable in 2022. On the importance of an arts organization’s home space or hub: “Place Matters. Make Sure the neighborhood feels your building is their community hall or assembly hall.” He digs in to that, suggesting presenters ask themselves about each event; why offer this piece of theater/music/dance/visual art in this community at this time? Other insights revolve around ideas such as, “Diversity and freshness are essential” and “Let audiences co-author meaning: experiment with social media.” The text branches out from there to having conversations with the business community, becoming cultural citizens through political activism. It addresses taking risks and supporting “Little League” players in the field, combined with audiences actively participating in the arts—moves like taking a salsa lesson, having a bake sale to benefit artists, are among other ideas that he champions. In 2022, these strategies remain relevant, necessary.

Killacky’s obvious enthusiasm for the arts does not mean the essays are cheerleader-ish or full of Hallmark card expressions—nor are they impersonal. Many of them include the terrifying lapses and betrayals of his physical body and the equally-tragic details of decimated careers and opportunities. Marvelously, important balance is maintained—avoiding maudlin self-indulgence—in essays that are personal, but also analytical contextualizations of the history and facts that governed his years of working in arts administration.

A piece written for VTDigger in July 2020 titled “Imagining a Post-Pandemic Art World” refers to the present as “this liminal moment.” He writes, “Art can no longer be treated solely as a transactional product with audiences as consumers. What is important now is how culture can be essential in our communities.” Further on: “Embracing this new normal will have profound impact as we slowly rebuild our social, economic, and civic lives.”

Amid the blunt assessments and the glaring light of Because Art‘s expert “autopsy” on the arts industry, a deep humanity and what might best be called an inner glow for art are still the most prevalent melodic lines. Reflecting on Bay Area writer Jaime Cortez’s wonderful Gordo, a collection of short stories set in California’s Central Valley in the 1970s, Killacky calls Cortez “part of the next generation of writers framing the intersectionality of what it means to be American today.” The same quality could be said to apply to the art and life of John Killacky.