The Berkeley Art Museum has set up an immense task in its newest exhibit, “Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration” (through December 11): to “consider the foundational roots of confinement from philosophical, sociological, theological, and art historical perspectives to better understand the fact that today’s mass incarceration crisis has been centuries in the making.” Not a easy feat for an art show.

Could a museum patron learn what a prison is, or what the “prison experience” is by visiting a museum? No. Could an art exhibit make contributions to our understanding of the subject? Certainly. “Undoing Time” takes an oblique approach to the subject of mass incarceration, approaching it from all angles but head-on.

Nonetheless, in doing so, does come to several provisional conclusions that are not incorrect: One, that the modern prison system is another iteration of previous historical modes that include enslavement and the plantation system, among others. Two, that prisons are not more humane depending on the perceived modernity of their era, which is to say, now. And three, that the prison system creates ripples of collective social trauma that include, but extend far beyond, the imprisoned.

Now is not a particularly popular time for a critical examination of imprisonment. The open revolt against the US criminal justice system that commenced in the summer of 2020 has been met with tremendous reactionary push-back—an increasing vilification of those forced to exist outside the law (the homeless, drug users, immigrants, the incarcerated, etc.) and most recently, the sabotage of those trying to de-carcerate the criminal justice system from within, such as San Francisco’s democratically elected former District Attorney, Chesa Boudin.

But the fact that this isn’t the political and pop-cultural moment of two years ago makes this exhibit even more compelling and necessary. For “Undoing Time,” the museum commissioned 12 artists to present new works that deal with the topic of incarceration, and the result is a strong exhibit that brings new insights on the artists’ own terms.

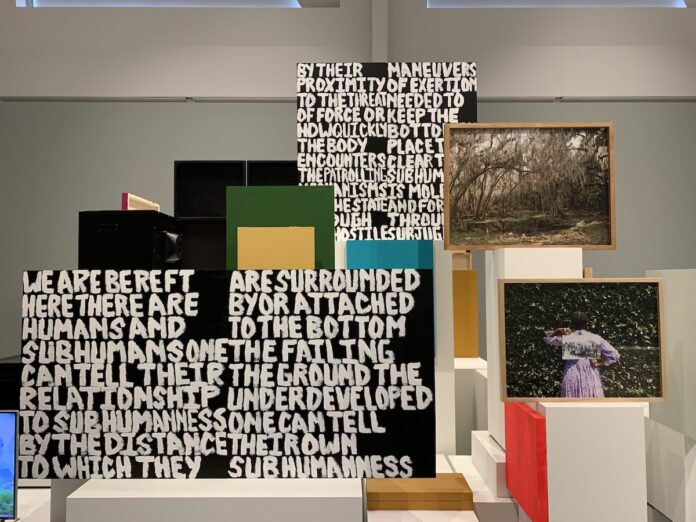

The show opens with a piece that grounds the entire exhibit by establishing the historical through-line that runs between slavery and the modern prison system: Skin Hunger (2021) by Black New York artist Xaviera Simmons. Within the sprawling, architectural, mixed-media assemblage (what the artist calls “a breath”) panels of text rise to form a communique on the subject of humanity and sub-humanity.

Panels read: “By their proximity to the threat of force, or how quickly the body encounters the patrolling mechanisms of the state through the hostile maneuvers of exertion needed to keep the bottom in place. To be clear, the subhuman is molded and formed through subjugation.”

“We are, have been and continue to be defeated in the ways that would render us fully human, so we turn our politics into representation while representation is the primary tool in our well-worn arsenal. Representation always guides us back toward and into sorrow, so we are imploding.”

Sub-humanity is a condition created through a state of subjugation. The prison system enforces this subjugation through the constant threat of violence. Representation, often the first in our line of attempts to make inhumane systems more humane, has its limits. Those limits are much more immediate than we would care to admit. The failure to permanently abolish this state of subjugation is our downfall.

Mario Ybarra Jr.’s “Personal, Small, Medium, Large, Family” takes a different approach. Ybarra’s installation recreates the artist’s hometown pizza parlor in Wilmington, CA. The piece is primarily concerned with the collective social and emotional fallout of incarceration; its centerpiece is a video interview that places the artist in conversation with a childhood friend recently released from prison. Together, the pair reflect on the friend’s 32 years of incarceration. Ybarra Jr. creates a space to talk about the effects of prison on both the incarcerated and their community: on the one hand, the great efforts required to maintain personal autonomy in prison, on the other, the vacuum created in their community by their absence.

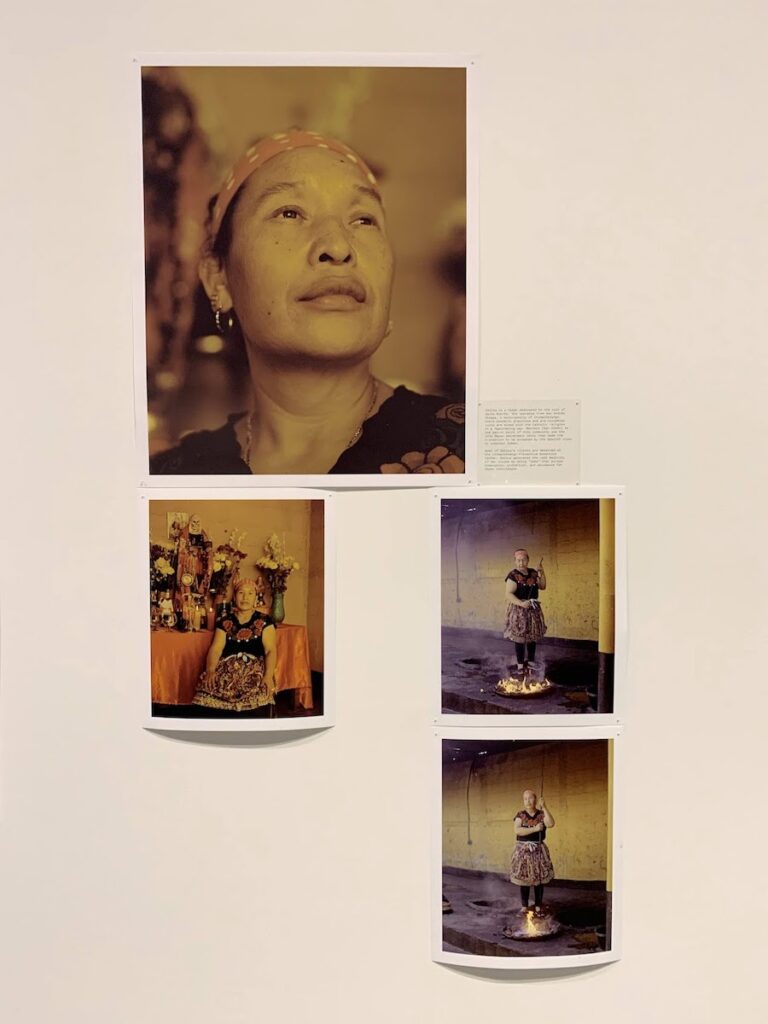

A common theme that runs through the show is the connection between prisons and the land. Prisons, after all, are not just sites of detention but also structures that exist in a complex geographic, economic, and physical space. Guatemalan artist Juan Brenner’s “B’Oko City of Walls” looks at some of the ancillary inhabitants of the carceral landscape. A local nurse denied the ability to effectively care for his imprisoned patients; a culandera who prays for the spiritual health of prisoners and their families; locals forced to watch their home, once considered a natural paradise, become a polluted wasteland. As the prisons sprawls outward, it drags everyone once living on that land into a mire of poverty, blackmail, and extortion.

Ashley Hunt’s work “Double Time” (2021), a series of photographs exploring the geography of prisons in the southwest, views the terrain as a kind of “palimpsest of multiple ruins of different regimes—settler colonial, missionary, military industrialist, racial capitalist—on top of one another.” Like, for example, the interrupted project of Reconstruction, when do we break the link? When do we finish the job? Prisons are not becoming more humane institutions by virtue of their continued existence into the modern era, but our modern era is made more inhumane by the continuing existence of prisons.

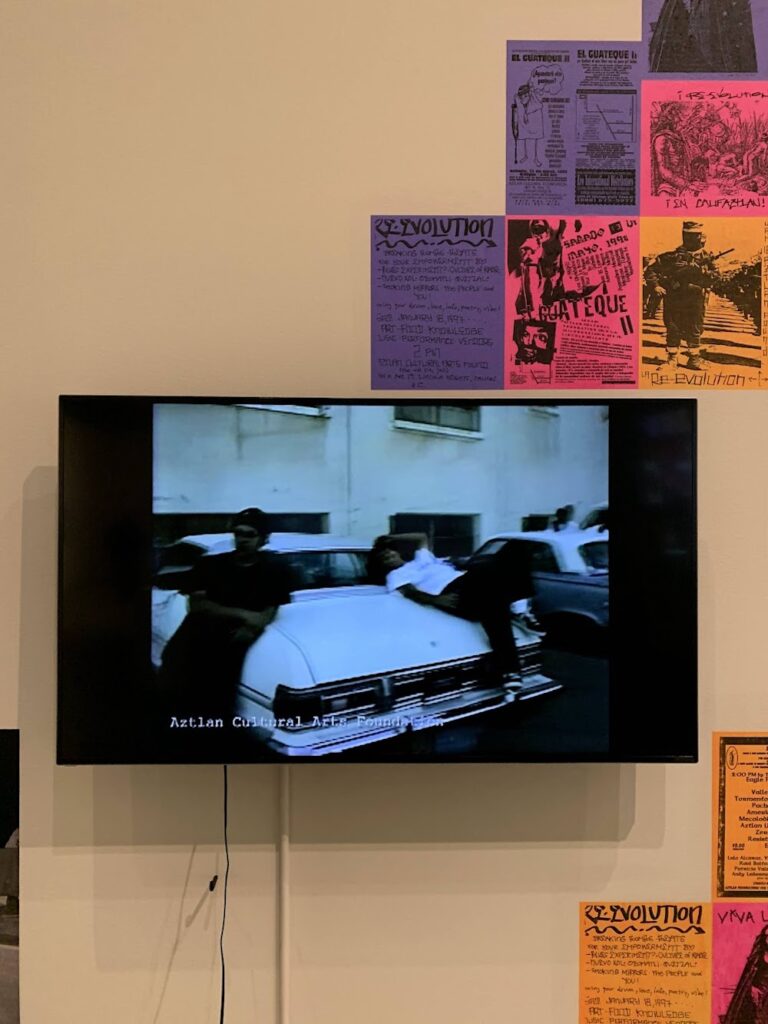

Sandra De La Loza’s “Unsettling the Settled: Archival Glimpses of Abolitionist Futures” (2021), documents the ad-hoc formation of a music venue and arts center reclaimed from the old Lincoln Heights jail in Los Angeles, which, before being decommissioned, held those arrested during the Watts Rebellion and the Zoot Suit Riots. Archival materials from the time, such as concert fliers and home videos show what is possible when a community seizes former sites of control.

The final piece of the show, Cloudroom, attempts to live up to the show’s original vision of exploring the image of the unfree subject across art history, collecting and presenting slides of historical images of prisoners, colonization, and enslavement. But at this point in the exhibition, that primary task feels gratuitous.

The museum should not need to justify itself by taking such an academic, multi-disciplinary, or highly structured approach in an otherwise enlightening show. Fortunately, it does this is in word only. The challenges of living up to the show’s own expectations do not affect the value of the individual pieces, which deal on a much more intimate and personal scale with the ongoing tragedy that is human caging.

“UNDOING TIME: ART & HISTORIES OF INCARCERATION” runs through December 11 at Berkeley Art Museum, more info here.