The subject was the cost of the city’s climate plan, but a hearing Wednesday at the Budget and Appropriations Committee revealed a crucial piece of information that hardly anyone at City Hall or in the news media is talking about:

To meet climate, housing, and basic infrastructure safety needs, San Francisco needs to borrow more than 20 times as much money in the next ten years as the city’s own self-imposed limits will allow.

Brian Strong, chief resilience officer for the city, and Controller Ben Rosenfield briefed the supes on the future of capital planning, and the message was dire:

There is no way to fund all the projects that everyone agrees the city desperately needs—unless the voters are willing to accept an increase in property taxes.

Strong pointed to at least $35 billion worth of needs, not including the $21 billion in the climate plan: $25 billion for affordable housing, to meet the state’s mandates. Another $5 billion to improve the seawall to prevent massive flooding linked to climate change. And $5 billion for emergency firefighting water supplies.

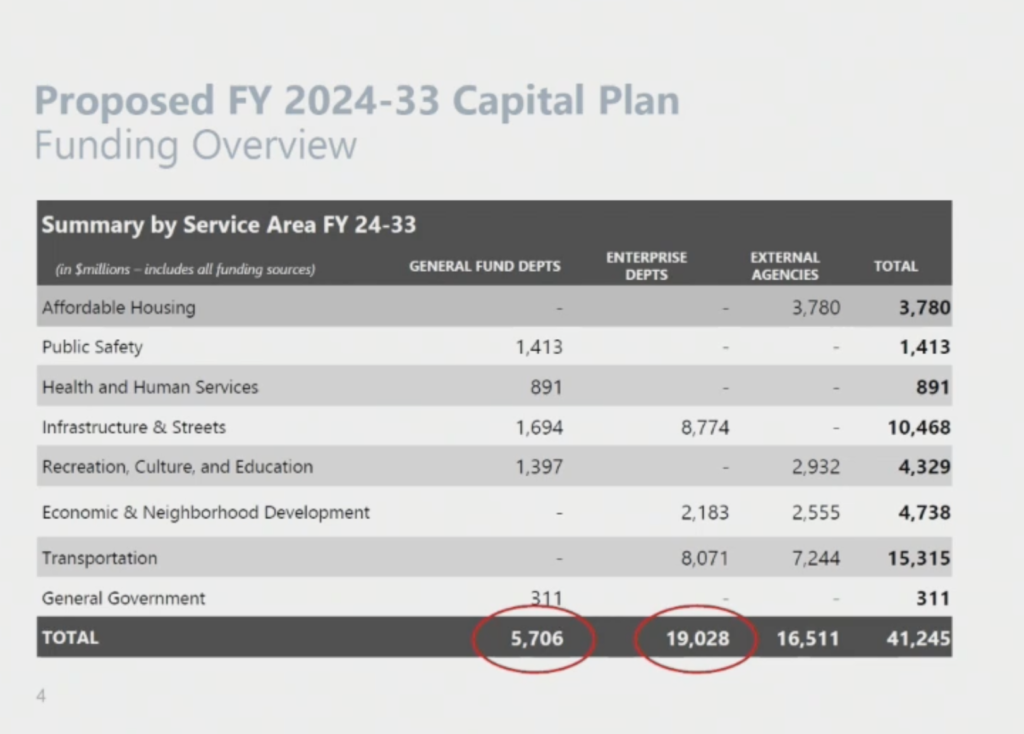

Then there’s all of this:

These are very big numbers.

But the city’s current capital plan addresses only a tiny fraction of the need:

That’s because policymakers decided in 2006 never to sell new bonds until old ones are paid off, so that the total property-tax bills on residential and commercial property will never exceed that year’s rate.

So right now, the total capacity limit for new bonds is about $2 billion. The $1.1 billion in bonds that the climate plan calls for would be more than half of that capacity.

“We are severely constrained over the next few years,” Strong said.

It gets worse: Since the bonding capacity is based on the total valuation of property in the city, when property values are rising we get more room to borrow money. But commercial property values are going down right now, so even that $2 billion in capacity might be optimistic, Rosenfield said.

The crisis, and it’s a real crisis, is both self-inflicted and the result of very bad state law and the power of credit agencies.

Thanks to Prop. 13-era rules, cities can sell general-obligation bonds, backed by property taxes, only with a two-thirds vote of the people. That’s a very high standard, when you consider that even in San Francisco, about 15 percent of the voters routinely oppose any new government spending. So bond campaigns need to get almost all of the remaining 75 percent.

And anything that smacks of a tax increase makes that even harder: Commercial property owners and residential landlords will oppose it, and since current city rules allow landlords to pass onto tenants half of the cost of bond-related taxes, a lot of tenants won’t vote for higher taxes, either.

That’s why the city decided in 2006 to set the cap on new bonds. It looks like this:

The gray lines are the bonds the city is currently paying for. The dark gray is bonds the voters have approved, but the city hasn’t yet sold. The colors are projections for new bonds over the next ten years.

The red line is the self-imposed limit.

The study looking at the cost of implementing the climate plan suggested, correctly, that the city could stop enforcing its property-tax cap and sell more bonds.

The only way I see that happening is if the city eliminates the tenant pass-through—and every local official, starting with the mayor, lines up in support of new bonds and raises enough money to fight the landlords.

Everyone who owns real property in San Francisco already gets a huge tax break from Prop. 13.

Meanwhile, the Wall Street credit agencies determine how much interest the city will have to pay on new debt, and if San Francisco borrows even a fraction of what it needs, those agencies will cry foul and investors will demand higher interest, making the cost of the bonds even higher.

I appreciate Strong’s honesty. What he is saying, in effect, is that the city is just going to fail: We will fail to protect downtown from flooding, fail to meet the state’s affordable-housing mandates, fail to protect residents from a catastrophic failure of firefighting water in an earthquake, and fail to implement the climate plan.

That’s what the “constraints” on new bonding mean.

With 60 billionaires in San Francisco, it would seem we could do better.