So much of “traditional” art is based on the white male gaze that it’s almost impossible to find a single work that doesn’t represent that excruciatingly particular world view. Opera’s recognized masterpieces are often defined by powerful women in the lead roles (Thaïs, Aida, Tosca, Carmen, etc.), but frequently reduce those women to damsels in distress and/or have them killed at the end. Even Mozart’s beloved The Magic Flute, often sold as an opera for children (and is part of SF Opera’s upcoming season), features a damsel in the lead, an anti-patriarchal queen being made into the villain, and a Black African slave who twice tries to rape the aforementioned damsel. The operas of yesteryear did indeed produce lasting masterpieces, but they were also made by guys who couldn’t—or, at least, refused to—see the world outside of their own myopic views.

So, how does one remount such a touchy work in a world more sensitive to other points of view? Well, one good way is that if the work revolves around a traditionally marginalized group, to let members of that group reinterpret the work.

That was SF Opera’s thinking behind their new production of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly (through July 1). The 1904 opera is an Italian’s exoticized view of Japan, based on an American short story. There’s little that can be done to change that, but the Opera was wise enough to hire Japanese director Amon Miyamoto to give the production more cultural accuracy. Puccini’s score is brought to life by famed Korean conductor Eun Sun Kim. Most noticeably, the principal Japanese characters—traditionally played by white actors in “Asiatic” make-up, if not full yellowface—are her performed by actual Asian actors, with various ethnicities for the chorus and supernumeraries.

That’s all fine and well, but what does it actually do for the opera itself?

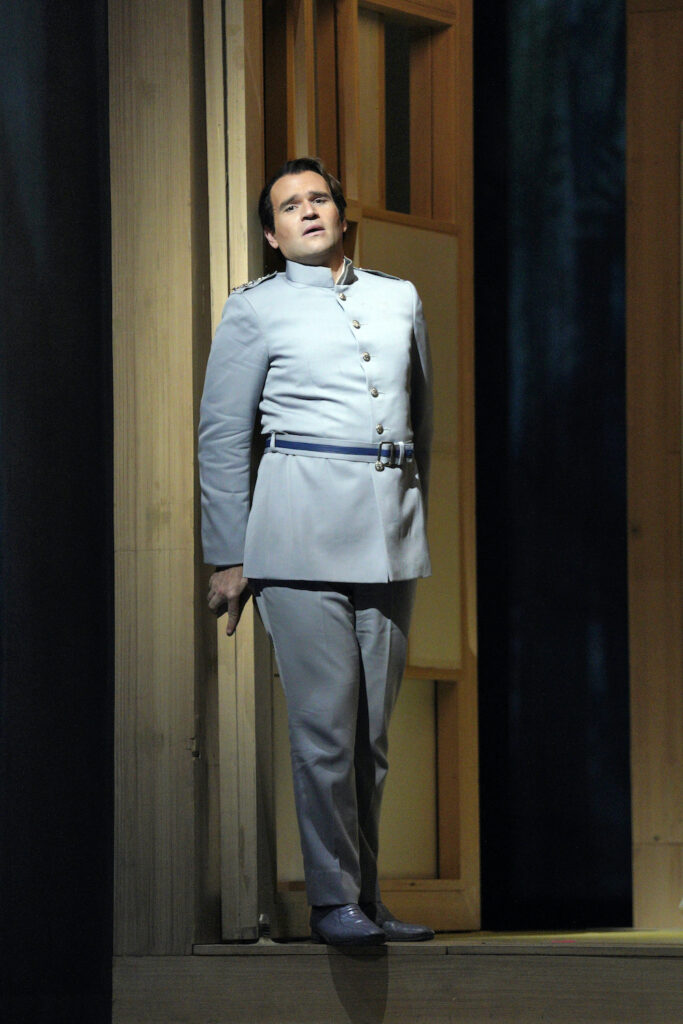

If you’re unaware, Madama Butterfly is the story of the eponymous Japanese teenager (played by Korean soprano Karah Son) whose real name was Cio-Cio-San. She is more or less bought by American Navy man Pinkerton (American tenor Michael Fabiano) as his child bride; an arrangement he plans to abandon whenever he wants. Cio-Cio-San is unshakably devoted to her new husband, so much so that she openly condemns Japanese customs and celebrates Pinkerton’s Christianity. None of this sits well with Cio-Cio-San’s family and neighbors. What’s more, Butterfly may soon discover that her marital love is one-sided, even when it produces a lasting consequence.

No one can fault you if the above description made you raise an eyebrow. This is one of those old Merchant of Venice situations where a beloved classic features a marginalized doing “the right thing” by rejecting their supposedly-heathen culture in favor of a place within The Church. It’s a story where an adult man taking a child bride is considered nothing out of the ordinary. It’s a story that puts forth the idea that, “yeah, some white folks are less than honorable, but the whole of Japanese culture is backwards!” Why would anyone want to remount it in this day and age?

Simple: “Un bel dì, vedremo.” If the title doesn’t sound familiar, I assure you that it’s an aria you’ve heard a thousand times, even if you didn’t know the title. It’s the aria Cio-Cio-San sings to voice her undying love for Pinkerton. If nothing else, Son is resplendent in the aria, truly making it seem as if she’s been preparing for role her entire life. Her performance may see her turning out towards the audience (or the prompter?) a bit too often, but she never falters on her notes.

In fact, the entire production is an enviable display of SF Opera’s technical prowess, from Boris Kudlička’s small rotating set (which recalls the similar set for The Paper Dreams of Harry Chin at SF Playhouse) being accentuated by Bartek Macias’ projections, to Kenzō Takada and Sonoko Takeda’s elaborate costumes. They give new visual life to the opera, as does Eun Sun Kim, who controls Puccini’s score the way a veteran athlete drives for a winning goal.

But, as they say, “the song remains the same.” They’re lovely songs, but they’re working from one of the same librettos (Puccini infamously went through five public versions of the opera, never seeming completely satisfied with each successive version) that isn’t all that different from how it was presented over a century ago. “Un bel dì, vedremo” is still gorgeous, but it’s sung by 18-year-old Japanese woman regarding her unwavering fidelity to the white man who has unapologetically abandoned her. There’s nothing in this production that challenges or refutes the racism of the text. It’s all just presented as if it can still be taken at face value. At least now, the face is one that doesn’t require special make-up to achieve “that Japanese look.”

One positive innovation brought to the show is the SF Opera’s continued use of livestreaming, (though not all performances are streamed.) Still, as older theatre patrons find it tougher to travel and many of us remain vigilant through this not-over pandemic, livestreaming and virtual archives will become all the more valuable for companies and for patrons alike.

SF Opera’s been streaming and archiving for years, and I keep hoping that the organization will go all-in with it, maybe even attempting something similar to the virtual Opera House from SF Ballet’s 2020 online showcase for The Nutcracker. This production’s livestream was very bare-bones, preceding the show with just a poster image before we get a live feed of the Opera House chandelier. The sound of the downbeat finds the camera tilting down over the audience (of which none attending appeared to be masked) and into the orchestra. An in-pit shot of conductor Kim is shown as she takes her place at the podium. Once she initiates the orchestra, we’re given a professional multi-camera view of the stage.

This is repeated at intermission and ends with rolling credits. Bare-bones or not, it’s still a well done stream.

That’s something with which you can’t argue about this production: it’s well done. You can question the need to remount such a racially-insensitive show (even with people of that race having significant roles in the production), but the production is given the royal treatment.

MADAME BUTTERFLY runs through July 1. War Memorial Opera House, SF. Tickets and more info here.