Think back to 2017. While a political earthquake had occurred with the first election of Donald Trump as President of the United States in 2016, global pandemics were the stuff of disaster movies, AI the evil-outlier in sci-fi novels, and cops killing unarmed Black and Brown people with impunity was yet to be indisputably exposed by our phone-camera society.

Sadly, despite belief the internet, technology, and evolved morality would open up global conversations in which every voice is heard and all people respected, real life threw up stop signs. In particular, within almost every sector and industry, the history, voices, and stories of marginalized people and communities continued to be largely overlooked, distorted, suppressed, erased, or most tragically, simply forgotten and faced with extinction.

That makes The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s “Rooted in Place: California Native Art” exhibition at the de Young vitally important. The new, four-gallery exhibit opened in August and refreshes the presentation of Native American art, “Arts of the Indigenous Americas,” previously on view since 2017. Rooted continues through December 6, 2026, and is the first in a series of exhibitions focusing on specific regions of Native California. The installation explores the art, land, people, and traditions of Northern California’s Karuk, Yurok, Hupa, Tolowa, Tsnungwe, and Wiyot communities.

Significantly, museum staff developed the exhibit in close collaboration with Indigenous scholars as co-curators and in consultation with communities of origin. The result is an exhibit not only filled with diverse items, but one that presents art and artifacts framed by a broad spectrum of curatorial visions. While not excluding anthropological perspectives that have long been components of exhibitions of Native art, Rooted opens the aperture on artwork spanning thousands of years by including not only the works of artists who lived or are living in California, but indigenous works from Canada and Mexico, as well as Ancestral Mayan art.

Highlights of the museum’s permanent collection are joined by new acquisitions and recent commissions that bring fresh energy and immediate relevancy to conversations about the future for contemporary Native American art and artists.

In an email interview, Hillary C. Olcott, Curator of Arts of the Americas at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, explains the organic evolution of the curatorial process. “The first members of the curatorial team and advisory group were partners from past projects. These individuals then invited others from their networks to join the re-installation project team. The resulting team comprises people from different Tribal communities, academic backgrounds, and generations, bringing a multitude of perspectives to the project. The curators and advisors helped facilitate communication with additional artists, scholars, and Tribal leaders throughout the project’s development and production.”

Olcott says the approach not only lends richness, liveliness, authenticity, and diversity to the exhibit, but underscores the de Young’s sincere commitment to building lasting relationships with individuals and other institutions.

The Co-Curators in addition to Olcott include Meyokeeskow Marrufo (Robinson Rancheria/Eastern Pomo), Joseph Aguilar, PhD (San Ildefonso Pueblo), Will Riding In (Pawnee/Santa Ana Pueblo), and Sherrie Smith-Ferri, PhD (Dry Creek Pomo/Bodega Miwok). A half-dozen additional advisers were integral to the process and indigenous community members and institutions from the areas of focus provided guidance for how to properly display the ceramics, textiles, paintings, beadwork, carvings, works on paper, basketry and other artwork. The protocols followed ensure the museum complied with the requirements of the now-established Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

In a separate interview, Marrufo reflects on joining the curatorial team and the valuable contributions Native California art adds to the museum’s overall collection. Stepping back to consider the exhibit’s role in the art industry overall, she suggests the blended experts-with-community approach to curation elevates the de Young’s reputation. The exhibit’s vitality and richness will lead to greater understanding and appreciation of Native art in all its fullness, according to Marrufo. And importantly, by unfolding the multiple connections with Native American communities—relationships to the land, systems of knowledge, traditional celebrations, language, and history—the visual elements and stories gain clarity and become irresistibly compelling.

Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and Lakota), “Special Forces,” 2025. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas,

“The biggest thing was to show a continuous, vibrant people. We are still here and still alive. There are so many beautiful things; items both contemporary and historical that show their intricacy, the complicated people we are, and our universal relationships and dynamics. We pull beautiful colors and shapes and design from the land. I want people to understand that we are vibrant. There are problems in Indian country, just as there are in the rest of the world, but there are also people creating these remarkable things and telling stories of who and what they are.”

Marrufo is Eastern Pomo. There are seven different dialects of Pomo language in the 26 tribes that live in three major geographical areas. “I’m from the Clear Lake county and there were originally over 30 village sites, but now, there are only seven East Pomo tribes. Our anthropological name, Pomo, was given because someone from outside came in and said we all wear the same clothes, we all dance alike, we are all in one location, we are all Pomo. We’re mostly known for our feather basketry, because of the amount of birds on our land.”

Pomo’s primary teachings are about community. “It’s the only factor, because we’re not talking about just the people within, that’s too compartmentalized. Where talking about a wholistic community. It’s not only the Pomo people, it’s the plants where you live, the dance regalia, the land, how we feed and clothe each other, and how we live within kinship and a multigenerational community.”

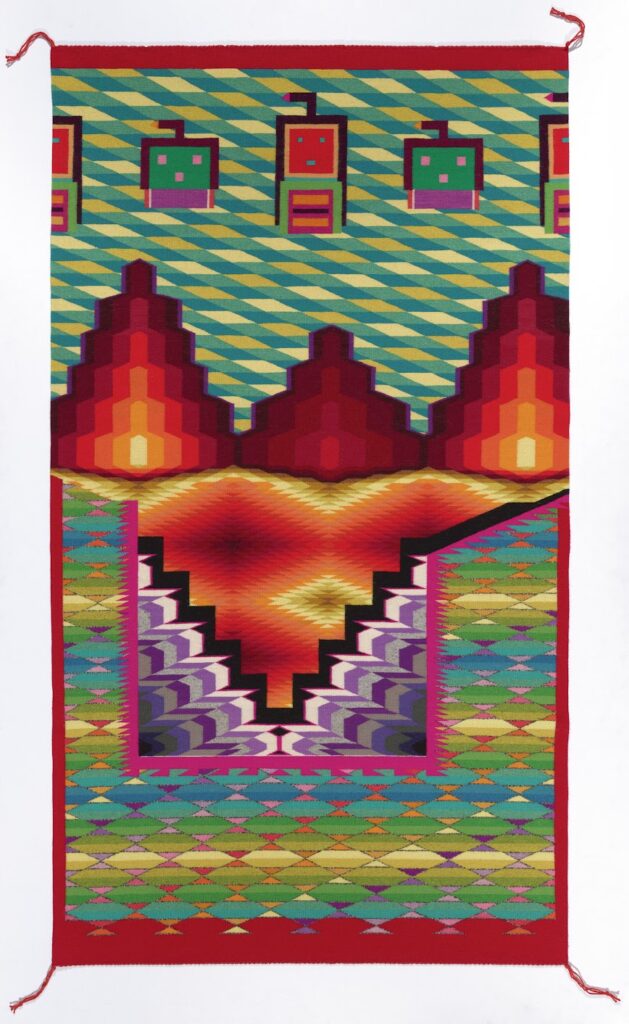

Melissa S. Cody (Diné) “Sailing the Cosmos,” 2024. Wool warp, weft, selvedge cords, and aniline dyes

Marrufo was a late-comer to “Rooted”‘s curatorial team. “I was invited by Sherrie, Joseph, and Will. They wanted another voice and Sherrie and Hillary recommended me. I saw that the advisory and curation teams knew it was important to talk to the people whose art they’re representing. Typically, museums have taken anthropological papers and designed labels that are very dry. We tell of stories of place and interestingly, a majority of items we brought in don’t have people’s names on them because it wasn’t important who made them, it was important what tribe they were from.”

Contemporary artists were brought in to give specific names to the art; honing down in some cases from tribal names to determine the actual weaver, ceramicist, painter, knot-maker, or textile artist.

Asked about the ways in which Rooted might serve as a model that marries art and ethnography approaches for other institutions’ exhibits of Indigenous art, Marrufo says. “Those two ways of displaying indigenous art seem not to be able to compromise. There are rules for art, and others for ethnographic exhibits. I’d like to find a happy medium and I think we’ve succeeded with Rooted.”

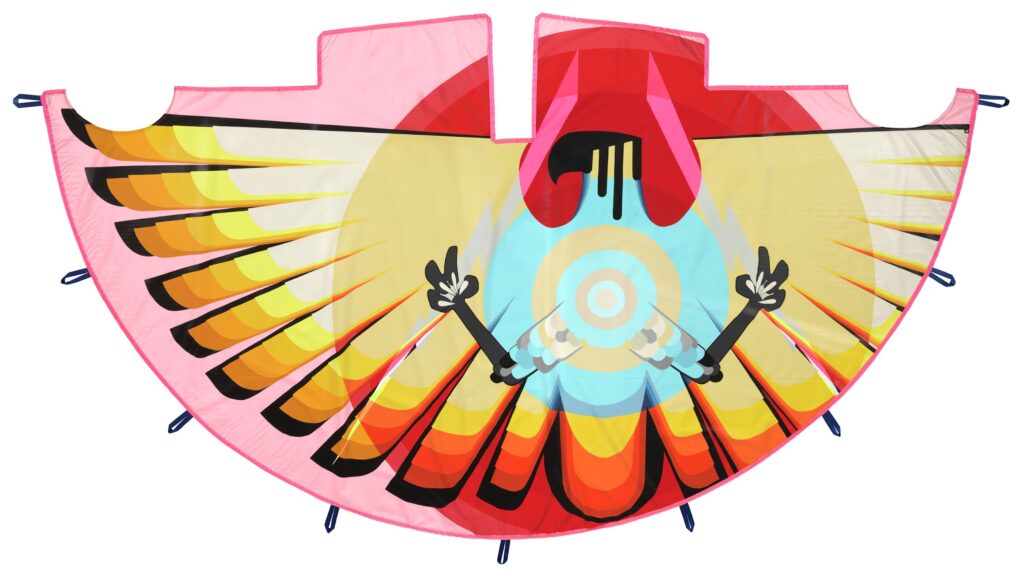

She mentions the pops of bold color brought in by the curatorial team that contrast the green theme of the overall exhibit design. Marrufo says bright color serves as a symbol; demonstrating each tribe’s expressivity, uniqueness and diversity. “One piece I love in the exhibit is a kite that’s a condor, made by L. Frank Manriquez. It represents her art but also the return of her non-federally recognized people to visibility. This massive, glorious condor shows we are still people of this land. We are rooted in this place.”

Olcott says although they have just opened the newly renovated Arts of Indigenous America galleries, the staff is already working on future changes. “The galleries will be a dynamic space where artworks rotate on and off view, and we are planning the next round of rotations for early 2026. We are also beginning to develop the next exhibition about Native California, focusing on a different region within the state, which will open in early 2027.”

To accompany the re-imagined galleries, FAMSF will be offering a new curriculum for educators and school tours and host a three-year series of free public programming highlighting Native American art. “Behind the scenes,” she says, “we continue consultations with Tribal communities of origin to develop plans and protocols for caring for their cultural items. So the work never stops!”

ROOTED IN PLACE: CALIFORNIA NATIVE ART runs through December 6, 2026, at the de Young Museum, SF. More info here.