Opera-lover Elaine Elinson is the coauthor of Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California, winner of a Gold Medal in the 2010 California Book Awards.

———-

It was a driving, restless population

It was the only population of its kind…

brimful of push and energy,

And endowed with every attribute

that makes a peerless and magnificent manhood.

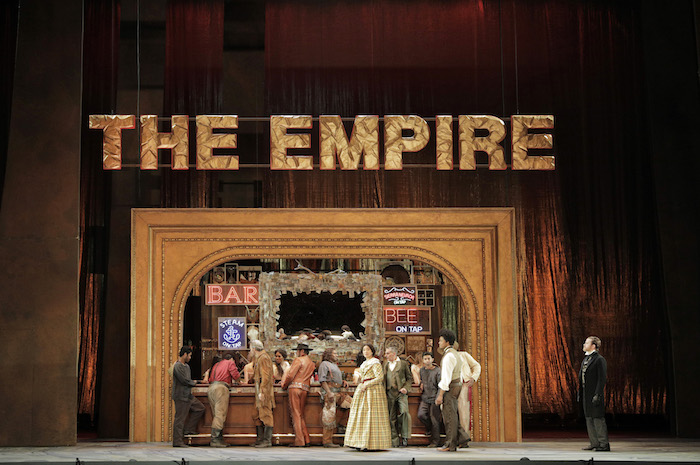

Forty-niner Clarence (Ryan McKinny) swings his pick, as he sings among towering, stylized redwood trees when the curtain rises on the premiere of new opera Girls of the Golden West (through Sun/10 at SF Opera) by John Adams and Peter Sellars. His words, adapted from Mark Twain’s “Roughing It,” pretty much sum up the idealized view of the Gold Rush that California students are still taught in school.

The bass-baritone’s boastful description, “It was the only population of its kind,” is followed by a scenic — if rather bumpy — journey by Dame Shirley (Julia Bullock) to the mining town of Rich Bar in a wagon is driven by Ned Peters (Davóne Tines), a fugitive slave turned cowboy.

But by Act II, the glories of the Gold Rush and even the wonders of nature have fallen prey to greed, racist violence, and misogyny.

The stage is dominated by the huge stump of a downed tree, no longer majestic. Its gigantic trunk is now a stage for a bawdy Fourth of July celebration, featuring barroom girls dressed in skimpy red-white-and-blue tutus and the infamous Spider Dance of Lola Montez (Lorena Feijoo). A raucous crowd of drunken men threatens Chinese miners, shouting “Yellow-skins, get out! Get out!” They whip, beat and slash the ears off Latin Americans, with cries of, “Death for all Chileans, Mexicans and Peruvians.”

Clarence’s words now reveal the miners’ bigotry: “We’ve got more gold than all the world…and prisons too, we’ve got the best. And smarter men to make us grow, than England, France or Mexico.” Though he sings “To one and all, both young and old, you’re welcome here, the land of gold,” the mob’s brutal actions belie his words.

Ah Sing (Hye Jung Lee) doesn’t feel welcome. She, like thousands of other girls, fled China to escape war, disease, and famine. In a liquid soprano voice, she tells of being bought for $7 at the age of 10 and sold into prostitution. With bitter pride, she relates that 10 years later she is now worth $700. A bill of sale from found in San Francisco library archives attests to the truth of her tragic history, it lists “Rice – 6 mats, $12., Salt fish, 60 lbs. at 10 cents — $6.00, Girl — $250.” Ah Sing’s aria, “A traveler on this shore, since coming to this frontier land, I bear all kinds of abuse…” is derived from the poetry carved into the walls of the immigration station at Angel Island.

Chinese and Latin American miners were not welcome – they were subjected to the Foreign Miners’ Tax of 1850, forcing them to abandon claims or go broke. Vigilante violence claimed many lives. An estimated 10,000 Mexican miners were driven from the gold fields.

In Downieville, Mexicans could not stake claims, so Ramon (Elliot Madore) and his wife Josefa (J’Nai Bridges) work in a gambling den. Josefa warns of the disaster she foresees in the tiny mining town, her velvety mezzo-soprano pulses with an undertone of fear. The Fourth of July celebration turns into a drunken brawl, and miner Joe Cannon (Paul Appleby) breaks down their door and tries to rape Josefa. In defense, she stabs and kills him. When the miners find Cannon’s body, they stampede to her adobe cottage. There she sits with a calm dignity, dressing and putting on her jewelry, to face the crowd.

It was fitting that Sellars included in the bedraggled mob a few rich fellows in fancy black suits and top hats. At the actual Downieville Fourth of July celebrations that year, there were many of those swells — including Colonel John B. Weller, a future governor; William Walker, who declared himself president of Nicaragua few years later, and, no doubt, several bankers ready to take the miners’ gold. None of them rose to Josefa’s defense.

A kangaroo court “tries” Josefa, and in the most heartwrenching moment of the opera, she takes the noose, singing in Spanish and English, and concludes with “Dios te lo perdone” (God forgive you).

Josefa was hung in a makeshift gallows over the Yuba River, the first woman to be lynched in California.

The original libretto by Peter Sellars was crafted from historical sources, the primary one being “The Shirley Letters,” by Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe, aka Dame Shirley. In addition to “Roughing It” and the Angel Island poetry, he also relied on miners’ ditties compiled in the “California Songster of 1854” and “Songs of the American West.” Frederick Douglass’s 1852 oration, “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?” is the basis of fugitive slave Ned’s stirring Act II aria.

I was fortunate enough to hear Sellars talk about his work prior to the performance. He explained that he used the letters of Dame Shirley because he found that not only did she write with grace, style and wit, but also because “she humanized all around her.”

When asked what relation his opera had to Puccini’s famous 1910 romanticized “Girl of the Golden West,” Sellars replied “Zero! Zip!” But if that is the case, I wonder why he and Adams did not call their opera “Women of the Golden West.” Surely, given the insight and literary talent of Dame Shirley, the resilience of Ah Sing, the compassion and dignity of Josefa and the sensuous agility of Lola Montez, that would have been a much more accurate title.

John Adams’ orchestration incorporates sounds of the California Gold Rush: cowbells, accordion, and guitar. In the program notes, the composer explains that because the Gold Rush lyrics are “as simple as can be…. It needs to have music that respects its own simplicity. My first impulse was that the sound and the orchestration should be as simple and as homely as the tools the miners use…”

Adams said he was inspired by the “ups and downs and flat areas and jagged shapes” of the topography of northern California to recreate those shapes “in musical time.” His dissonant and sometimes jarring signature sounds mean that audience members will not be humming memorable tunes when they exit the theater. Even familiar old chestnuts like “Camptown Races” and “Pop Goes the Weasel” are rendered unhummable in Adams’ unique score.

Sellars readily concedes that he took some poetic license with the historical facts. The real Josefa Segovia (also known as Juanita) was hanged over the Yuba River in Downieville in 1851, and there was one person — Stephen Field, then alcalde of Marysville and later a justice of the California Supreme Court — who tried to speak in her defense. He was violently silenced by the mob. Dame Shirley may have heard about her murder, but she didn’t witness or write about it.

And the Ned of Dame Shirley’s letters did not drive her in his wagon to Rich Bar, but was hired there as her cook. He played the violin so beautifully, they called him Paganini Ned. He would not have known Douglass’s speech, as it was not written until 1852, but he definitely would have feared for his life since slavery was still practiced in California. The poetry that is the basis of Ah Sing’s aria comes from the walls of the immigration station at Angel Island, which was not opened until half a century later, in 1910.

But though the facts may have been manipulated, the essence of the stories are very real: a Mexican woman was lynched by a mob of white miners, Chinese women were trafficked by the thousands, Latino and Asian workers were brutally beaten in the minefields, and the freedom of fugitive slaves in California was not guaranteed by law.

In Girls of the Golden West, Adams and Sellars debunk the dominant narrative of the history of the Golden State. In the unlikely setting of the San Francisco Opera House, we hear the powerful voices of the women and people of color who both endured and defied bigotry and injustice. And for that, we shout, “Bravi!”

GIRLS OF THE GOLDEN WEST

Through Sun/10

War Memorial Opera House, SF.

Tickets and more info here.