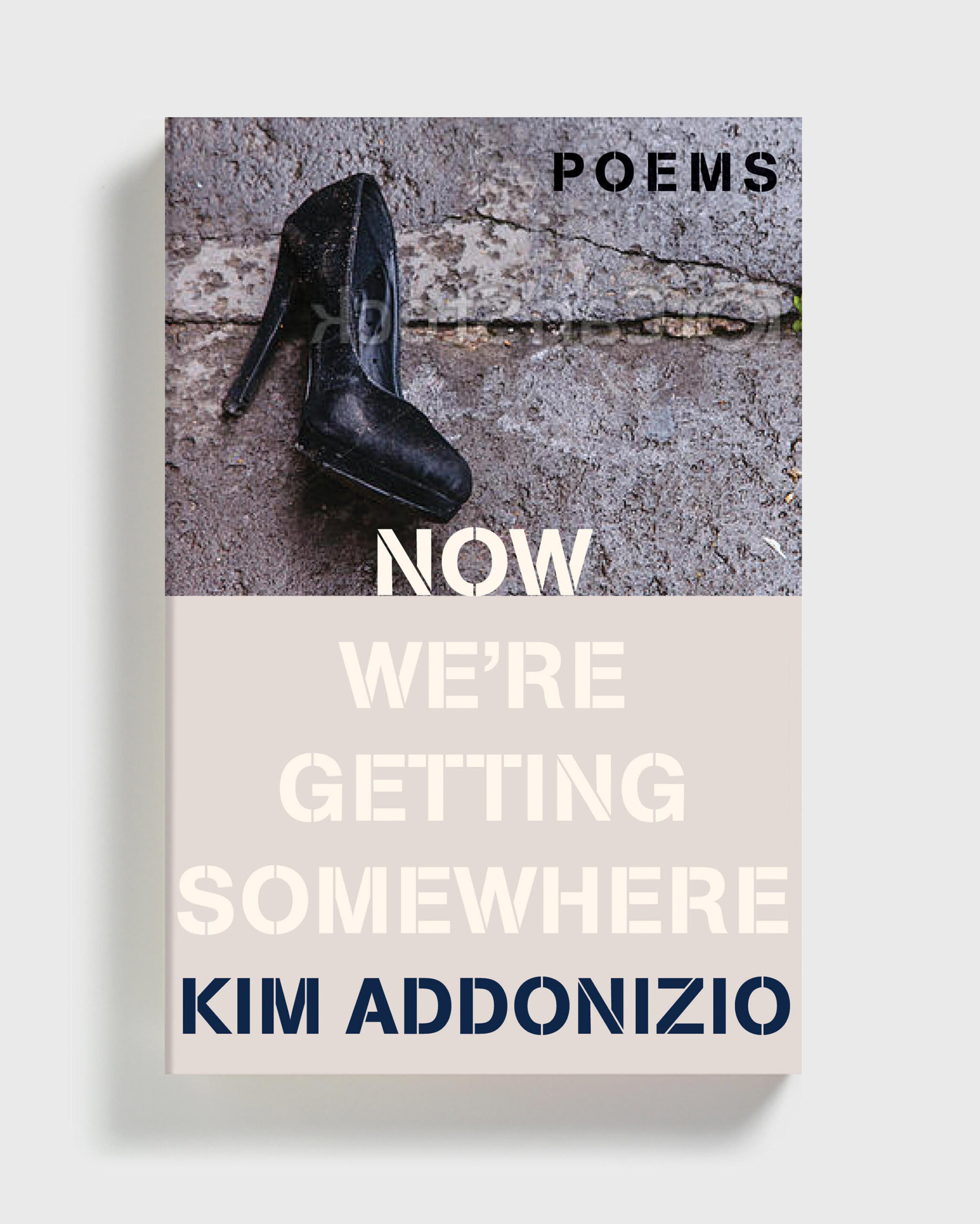

Shortly after a 90-minute phone conversation with San Francisco-based poet Kim Addonizio about poetry, I add two items to my earthquake emergency preparedness kit: a copy of her latest collection Now We’re Getting Somewhere (W. W. Norton), and a handwritten 3×5 recipe card penned by my mother for Blueberry Stuff. The book with 38 poems by Addonizio delivers enough electricity to light up any room—or light up a reader’s imagination, raging mind, gentle and/or isolated and suffering heart—during a blackout. The Blueberry Stuff? A three-layer dessert regrettably allowed by my mother to be named by her less-than-poetic daughters, and without which my young life would not have been survivable … or at least, not nearly as enjoyable. I never want to forget how to make it.

Addonizio is the author of seven poetry collections, among them Tell Me, a National Book Award finalist, and Mortal Trash, winner of the Paterson Poetry Prize. Her prose work includes two story collections; a memoir, Bukowski in a Sundress: Confessions from a Writing Life; and two books on writing poetry, The Poet’s Companion (with Dorianne Laux) and Ordinary Genius. Addonizio also has two word-music CDs: Swearing, Smoking, Drinking, & Kissing (with Susan Browne) and My Black Angel, a collaboration with woodcut artist Charles D. Jones. Born and raised on the East Coast, Addonizio later moved to San Francisco and earned a B.A. and an M.A. from San Francisco Stage University. She has received two fellowships from the NEA, a Guggenheim, two Pushcart Prizes, and other honors.

In our interview, Addonizio tells me she recalls being “a big reader” during her childhood. Frequent trips to the library occurred and the borrowing limits of three-books-per-card didn’t curtail her enthusiasm. “I’d just borrow my two brothers’ cards and take out nine,” she says. “I remember my mother [tennis champion Pauline Betz] used to read to us the Greek and Latin derivations of words. She always had an ‘improve your vocabulary’-type book around. My dad, Bob Addie, was a sports writer, so words were everywhere in our house. The books I remember them reading were the big glossy bestsellers of the day. I would find the dirty parts of The Godfather and read that.”

When I ask her if she’s had a third “struck by lightning” experience equal to the two she referenced in a past interview (discovering poetry and encountering the blues in music), she speaks of folk song “Boil Them Cabbage Down” and her love of a new stringed instrument. “I’m feeling intense about my Resonator banjo right now. It’s loud, amazing. I play it every day and neglect other instruments. I’m at the basic level. I used to play it fingerpicking like playing the guitar, and now I’m back to the basics and bought some metal picks. I love being a beginner. ‘Boil Them Cabbage Down’ is just three chords. I love the sound of it and hope to incorporate it into my readings.”

The banjo may or may not bring on radical epiphanies for Addonizio, but listening to the rhythms and patterns of words in poetry and in music remind her of kinship between art forms. “Keats called poems ‘breath sculptures,'” she says. “When I read my own poems aloud I don’t always nail it. I’ve heard other people read my work better than I can. And some poems are meant to be only in that space between a writer and a reader. That’s a very private and special place.

“Dead poets of the past, I will never hear them but I hear those voices speaking to me. I’m in dialogue with that art, advancing it or repeating it. I feel the connection more deeply and sometimes I don’t want to hear their poems read because it might spoil what I have with them; the relationship I have with them on the page. What you get from a work of art—including music—is an intimate feeling that the work is yours. Someone else wrote the song or painted the painting, but you feel it’s yours because you have a private connection, a sense of presence in a piece of art that doesn’t require the artist to actually be there.”

Art songs or poetry set to musical accompaniment, she says, create ambience for stand-alone poems. She has discovered that words extended or rhythms altered in poems in response to musical phrasing or textures gives the original work added dimension. “Music can evoke emotions without language and poets rely on words to get there,” she says. “Sometimes music feels like a more direct line to what (poet) Donald Hall calls ‘the unsayable said.’ We as poets hope to get from that gap between words and what those words are trying to get to; to the mystery of how something feels.”

In the new collection, she grouped the poems into four sections to provide nominal structure; Night in the Castle, Songs for Sad Girls, Confessional Poetry, and Archive of Recent Uncomfortable Emotions. “It starts with political global poems,” she says. “Then Songs for Sad Girls is like a musical suite and are more troubled poems, and then the confessional poem I hope creates a context for other pieces and pushes back against conflating a poet with the poems. Then you read the final poems not as ‘this is Kim talking about her life,’ but instead it’s a fiction I really want you to believe. You know it’s made up, but you forget that, if you’re invested in the story. You enter a narrative that feels real.”

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Addonizio supposes that if a reader thinks a voice in a poem is hers and the events or thoughts are autobiographical, she’s done a good job of writing with an authentic voice. “But it they read a poem about drinking and ask me if I’ve been drinking that day, it pisses me off. It says they’re not reading seriously. To take it as the surface level and assume a poem is about me having an affair in Italy, when it’s about a Dante quote about living with hope and desire—that’s fine if you’re a reader and getting something from it, but not OK if you’re a professional critic and not paying attention, not being aware.”

The comment about critiques of her work causes me to ask if there is something true about her work that is often overlooked or too-often mentioned. She likes the question and says reviewers often label her poems as “racy” or “sexy,” or words to similar affect. “I don’t think [my work is] particularly brave or edgy. I don’t experience it that way and wonder why other people do. I wonder if they have cable TV, which is much racier and sexier. It’s funny that they see it as raw. I just write about life I’ve experienced.”

And what is overlooked? “People don’t address my ideas very often,” she says. “They focus on drinking or that I said the word ‘fuck.’ It puzzles me that poetry should be held to an ethereal standard of purity. That’s not what it’s been about, ever. It’s about the experience of mortal life. It’s an exploration of what it feels to be human, to live in a body that passes.”

Another blind spot caused by conflating poet and poem—especially when it comes to sex and sexuality—is a critic losing focus on craft and instead indulging in sensationalism. One male critic was completely dismissive and said he didn’t want to be a stick of butter in her mouth—a snarky, disparaging “I wouldn’t want to go on a date with her” dissension. “Writing in a way that is direct is threatening to some men,” says Addonizio. “On the other hand, it doesn’t bother me anymore. I don’t feel hurt about it, I just feel pissed about it.”

She might be pissed, but that doesn’t make her careless or retaliatory. In the new book, she used “shit” often and was later bothered with worries it might feel gratuitous. “If you’re doing it deliberately for a reason it’s OK, but you don’t want to use a word to ramp up energy or try for intensity with a word because it’s not the best way to get there.” A few poems end with “just listen,” a way of turning to the reader with an overt, inclusive address. “I love that Whitman in his poems looked for me; saying ‘this has happened with me in the same way it is happening to you.’ I take that concept to heart when writing to people I don’t know or to people who haven’t been born yet. It’s a way of giving back to what I’ve gotten from language.”

Most gratifying are young women who write Addonizio to say she gave them confidence. “Especially when it comes from young, confused girls,” she says. “I realize there’s a generation coming up behind me that is feeling these feelings and trying to write about them too.”

Wrapping up the conversation and preparing to rejoin the real world, I ask Addonizio to speak briefly on three poems from the new book. “Ways of Being Lonely” is culled from reordered ideas and a search for less predicable metaphors that break patterns of thought to “wake me up” without resorting to pyrotechnics. “Little Old Ladies” is a pushback. “This fucking youth culture,” the poet says. “After 25, we’re supposed to wander off and die in a sand trap. We’re not fuckable, we’re expendable. It’s ‘take this for your eye, your liver, buy your Depends.’ It’s insulting.”

“Fixed and in Flux” started with cicadas, although that’s not where it ends. “Attracting a mate and thinking about children was where I went from the cicadas,” she says. “Once I saw the direction, I revised and it became about what is fixed, what is cyclical or changes. There are images that are about existential concerns, underwater mortgages, the degradation of the world, the cyclical nature of having children and other, unsettled things.”

Shaking herself awake, rattling a few cages in need of rattling, we’re back where we started; thinking about earthquakes. I don’t know when the next big one will come, but I’ll have Addonizio’s poems for companionship and the recipe for Blueberry Stuff for sustenance. If you want the recipe—well, it’s a family secret, but let’s agree that in an emergency, certain rules are meant to be broken and besides, sharing is good when it comes to dessert—and poetry.