With many works in earth-tone palettes and natural materials, “The Missing Circle” at KADIST (through January 8, 2022) links nature, decay, and death with the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, political turmoil, inequity, and mass murder in Latin American histories. While the exhibition nicely showcases many Latin American artists and the complex histories of the region, it also creates questions about who has the right to depict global narratives, albeit the organization’s restraint of exhibiting mostly works from its own collection.

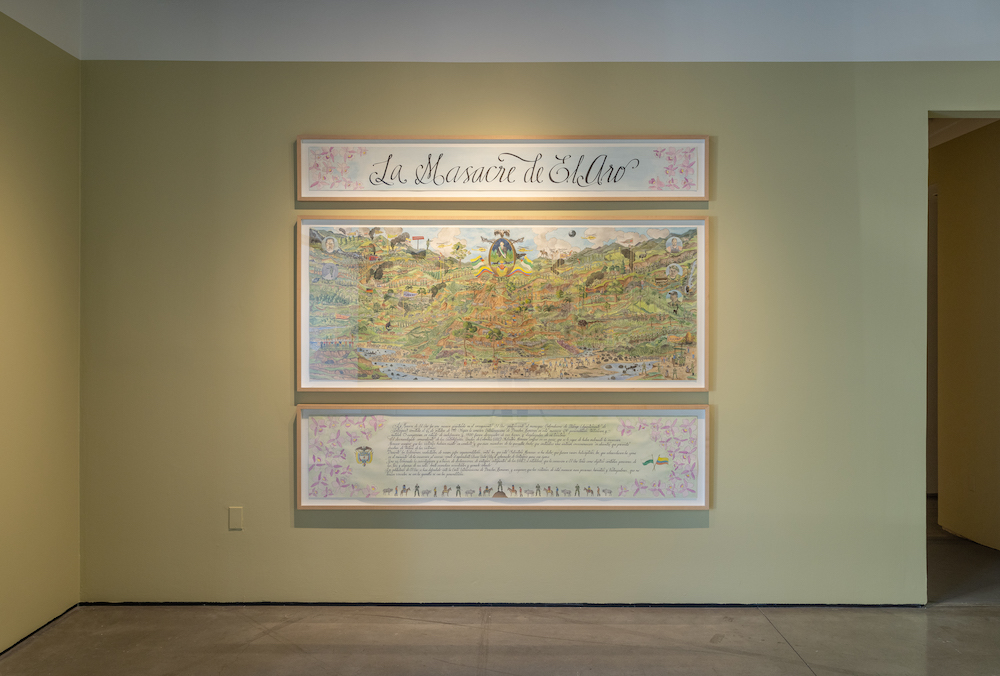

Of the strongest works in the exhibition, Jorge Julián Aristizábal’s vibrantly colored drawing breaks from the muted color and poetics of much of the exhibition. Mining a complicated space between illustration and colonial-era documents, Aristizábal boldly depicts the 1997 Colombian El Aro Massacre. In the densely detailed drawing, a lush green hillside is dotted with decapitated heads, helicopters, money bags, and paramilitary troops with rifles. Aristizábal explicitly names locations with colorful flags and identifies key paramilitary agents, like Salvatore Mancuso and Carlos Castaño, in handwritten in cursive and in portraits flanking the sides of the images. In the top center of the drawing, Aristizábal positions a portrait of Álvaro Uribe Vélez, the then governor of Antiquia and Colombian President 2002-2010. With strings attached to Uribe’s, fingers, like a puppeteer, the artist presents a direct critique despite the work’s playful appearance.

Moving from metaphor of political puppetry, Carlos Amorales’ striking 2017 black-and-white film La aldea maldita (The Cursed Village) employs simplistic cut-outs puppets to chronicle a family as they move to a village and are lynched. With extremely simple production levels, void of complicated post-production and CGI wizardry, Amorales establishes a palpable tension as the family slow creeps through a shadowy forest while menacing figures lurk in the background. Like bird calls or a staccato computerized sound, Amorales’ soundtrack of whistles suggests communication, which on the bottom of the screen appears to be translated into a simplified form of a pre-Colombian writing. As the family is attacked, the camera pulls back to a contextual shot that reveals five musicians frantically playing around the set. Like the haunting fables of the Brother’s Grim, Amorales’ simple paper cut-out set poignantly balances a directness with coded language an horrific event.

While the first two galleries contextualize the works from many Latin America artists on a range of subject matter, the exhibition rather disjointedly coalesces in the third gallery on place, specifically Chile’s Atacama desert. In addition to its harsh geography, the Atacama is the place where Augusto Pinochet brutally dumped and executed many political rivals and dissidents, which was powerfully addressed in the Chilean filmmaker Patricio Guzmán’s “Nostalgia for the Light” (2010). With works by French artist Pierre Huyghe; Romaetti Costales, the collaborative duo of French artist Julia Romaetti and Belarusan artist Victor Costales (based in Mexico City); and the sole Chilean artist Cristóbal Lehyt, the Atacama is represented in photography, sculpture, and drawing that explore that deterioration of the body and nature, specifically through bones.

While an arresting image, Huyghe’s “Dead Indian Hill” (2016) is particularly problematic. As the image depicts the skeletal remains of a presumed mineworker in the Atacama, Huyghe ventures into exploiting the tragedy of others. Moreover, as with Huyghe’s work based on the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, this work seems like another example of the shape-shifting, global art star parachuting into places without a personal investment in the local.

While many of the detailed histories invoked in the “The Missing Circle” may be unfamiliar to San Francisco viewers, it creates conversations and forces us to reach beyond our comfort levles and knowledge. With many artists from across Latin America or ties to Latin Caribbean histories, with the exception of Huyghe, the show has sensitively considered the importance of authorship within a global art community.

“THE MISSING CIRCLE” runs through January 8, 2022 at KADIST, SF. More info here.