Faith Ringgold has built an astonishing body of work. A political activist born in 1930, Ringgold kept evolving as an artist as she fought for civil rights as well as gender equity. Her work includes soft sculptures, children’s books, story quilts, paintings, and performance and political art.

“Faith Ringgold: American People” at the de Young Museum (through November 27) is the most comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s work so far. The show has pieces from Ringgold’s first exhibition, “American People,” with paintings such as “The Flag is Bleeding” (1967) and “For Members Only” (1963). Attendees will also encounter her “Black Light” series, which includes political posters like “Free Angela” (1971), referencing Angela Davis, the powerful leader associated with the Communist and Black Panther Parties.

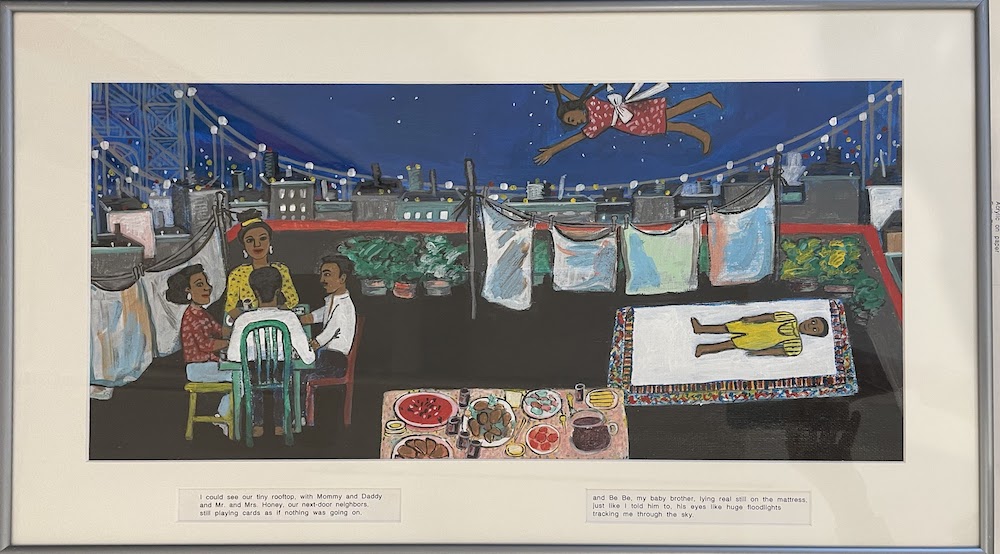

Ringgold’s “Feminism Series” is there, with its landscapes painted with the words of important Black women, as are her story quilts, including those in “The French Collection,” which features a fictional expatriate artist living in 1920s Paris. Many will thrill to the inclusion of images from Tar Beach (1988), Ringgold’s children’s book about a little girl in Harlem who can fly—and also make anything she flies over hers.

Pro tip: the de Young is free to all Bay Area residents on Saturdays, so if you’re local and come on that day you can see the show and one of its public programs, which include quilt making workshops and a jazz performance.

Curator Janna Keegan spoke with 48 Hills about why Ringgold started working in textiles, how Tibetan thangkas inspired the artist, and how Ringgold practiced a kind of speculative fiction—especially on view in her quilt scenes set in Paris.

48 HILLS Could you talk about the title of the show?

JANNA KEEGAN “America People” was the name of her first exhibition, and [we are showing work from that show’s series] in our first gallery. In it, she’s serving as a witness to history. When you think about her new “American Collection,” she’s going back and correcting the American historical narrative to point out the omissions.

48 HILLS What are some of the pieces in the show that do that?

JANNA KEEgAN “The Flag is Bleeding,” I think, speaks about the omission of Black women and their centrality to American society. It’s the third or fourth time Ringgold’s visited the theme of the American flag. We see “The Flag is Bleeding” in the first gallery. But in that piece, there’s no Black woman—and that’s an obvious omission, right? The needs of Black women weren’t being served by either the feminist or the Black Power movements. In “Flag is Bleeding #2,” she brings back a vision of motherhood with two children that very much parallels her own family.

48 HILLS In the “Black Light series,” she moved away from using white pigment. There’s some obvious significance there, but what did it mean in the context of her work?

JANNA KEEGAN She had traditional art historical training, which is where you copy the masters. She noticed that the Eurocentric palette is very heavily based around white paint, and so she tried to remove that. In part, because she found that there was a flatness of tone when she would try to paint Black skin tones. It didn’t really convey the nuance, or the variety, or the brilliancy of Black skin tones that well. She was able to bring out more nuances with darker tones. It was an incorporation of the idea that Black is beautiful into her color theory.

48 HILLS Could you talk a little bit about her children’s book Tar Beach?

JANNA KEEGAN We have the quilt from the Guggenheim, which shows [protagonist] Cassie Lightfoot and her entire family on their rooftop. This goes back to Faith’s childhood, when she says she used to hang out on “Tar Beach” with her family, in the summer in Harlem. Obviously, New York City gets very, very hot in the summertime, so escaping to the rooftop provides a little bit of breeze. And she could see the George Washington Bridge from her rooftop, and she always calls it her bridge. And in that way, Cassie Lightfoot is a little bit of a surrogate for Faith. You have this entire family enjoying the night on the rooftop, but Cassie has a superpower, which is she can fly. And whatever she flies over becomes hers. We’re lucky that we have all the painted illustrations for the book Tar Beach also in the galleries.

48 HILLS What about her story quilts? Would you say that’s what she’s best known for?

JANNA KEEGAN I think, within the art historical world, probably. She’s also known for looking at a broader segment of society. I first knew her as a children’s storybook writer. I think that’s probably her broadest impact across multiple groups. But within art history, she’s certainly known for her story quilts. And a large part of that is because she’s working to break down the distinction between textiles and craft-based medium and painting and sculpture.

48 HILLS Why was it important that she started working in textiles?

JANNA KEEGAN It’s something that has been traditionally associated with feminized labor. And in art history, the definition of art and craft usually tends to run along gender lines. The mediums that were taken over by men, which are painting and sculpture, were “fine arts.” And then the ones that were mostly the purview of women, like textiles, ended up being called “craft.” I do think it’s part of the feminist movement that she is reclaiming this.

48 HILLS Why did thangkas, the Tibetan Buddhist paintings on silk, inspire her and how did they show up in her work?

JANNA KEEGAN For one, it’s really practical. Working in fabric, she talks about that as being her independence, because it wasn’t as expensive to ship works of art when you could roll them up and carry them. Shipping frames can be really pricey. So, it is about independence and about being able to show her work to more people.

Also, I think there’s a meditative aspect of Tibetan thangkas. She puts these important feminist posts on them that relate to Black women. She writes them in a Western alphabet, but in a vertical orientation, which isn’t the orientation in which we usually write Western script. It slows down the readers’ experience, and lets them get into the works more.

48 HILLS Have you seen that happening with people in the galleries?

JANNA KEEGAN Yes. And we’ve had a lot of people in the galleries too, so that’s been really great.

48 HILLS What do you hear from people that they’re excited about?

JANNA KEEGAN Yesterday, we gave a tour to a group that does community service at a church in San Francisco. They were inspired by Faith’s total oeuvre, but also her activism. As a community service organization that serves San Francisco, there was a lot within Faith’s work that they were also trying to do, and could also connect to.

48 HILLS What about her activism inspired them?

JANNA KEEGAN In the 1970s, she would go out and organize protests against major American museums—namely, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum. She was going after them for not having enough representation of Black artists, and specifically Black female artists. She worked with Lucy Lippard to point out how gender-skewed the Whitney Annual was at that time, and they went into the galleries and they blew whistles and caused a big disruption at the opening. She also petitioned with other artists like Tom Lloyd for the creation of the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Black and Puerto Rican Art at the Museum of Modern Art.

She did not get the Black and Puerto Rican wing, but I will say this last Whitney Biennial—which is what the Annual turned into—did have parity between genders, and it was the first one to have parity. So, did she achieve her goals? I think we will get there. Faith is such a vanguard. This is really important in museum culture because we are having these conversations about equity within the museum and about representation. It’s important to note that that Faith was doing this [long ago], and to listen to and follow her lead.

48 HILLS What do you feel like was the most interesting thing you learned about Ringgold and her work while curating this exhibition?

JANNA KEEGAN I think it’s her relationship with children. She really does have a deep, deep care and affection for children. They are often her subject, but she also considers them as an audience, which is terribly clever and terribly subversive. You can get a younger generation into your art, if you can convince them of your beliefs in equity. Then you’re creating the next generation of activists.

48 HILLS And have you seen a lot of kids in the galleries?

JANNA KEEGAN Yes, and I’d like to see more.

48 HILLS In your essay, you write something about how her work is a sort of speculative fiction.

JANNA KEEGAN I think the French collection is a great example of speculative fiction, because she is putting the character of Willia Marie Simone—who is a composite of her mother, Willi Posey, a bit of Faith, and a bit of historical figures like Josephine Baker—into the 1920s Parisian art scene. Expatriates who were living in Paris in the 1920s, Black female expatriates, had a greater degree of freedom there than they enjoyed in the United States—but not to the degree that Willia Marie is enjoying in these works of art. And so, the Black speculative fiction is creating this moment where it’s like “what would have happened if we’d had enough support in place for an artist like Willia Marie to thrive during that time, what would be the world we’re looking at now?”

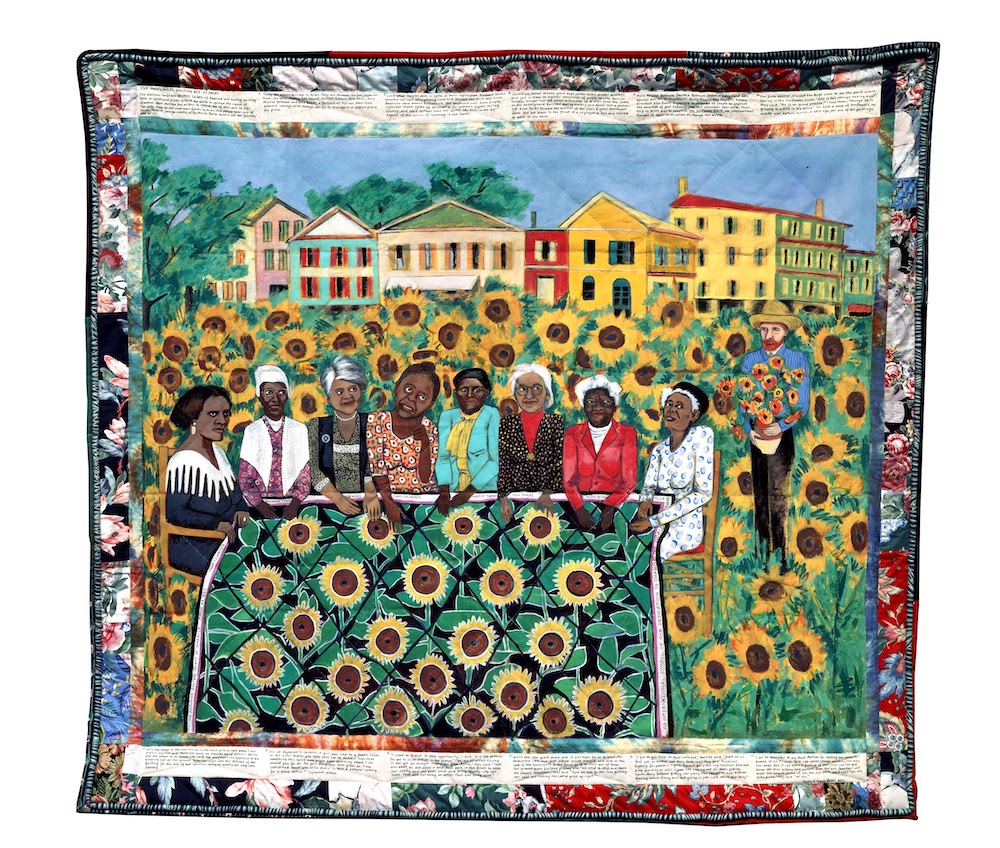

I think one of the most powerful works in the French collection that talks about that is “The Sunflowers Quilting Bee at Arles,” where you have Madame CJ Walker, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, and Ida B. Wells all together in a quilting bee. And the thought is, “What could these women have accomplished?” What could these women have talked about at a quilting bee, which were very social events? You sit and you talk while you sew, and here are all these great women with all these great thoughts. If they had gotten together in one place at one time, what might the world look like?

48 HILLS Can you talk about the diversity in forms of art that Ringgold used to create?

JANNA KEEGAN I heard there’s about a dozen media that she actually goes through. She does painting. She does soft sculpture. She does textile art, painting on textiles. She does story quilts. And then there are her children’s books. She has a world doll collection. She also did performance art. We don’t often think about her as a performance artist, but she really was, I think, on the cusp of that movement.

48 HILLS What has been you most liked about having this show here? I realize that’s a big question.

JANNA KEEGAN That’s a huge question. I mean, I’m really pleased that we got to bring the show to a Californian audience. I know Faith is so often associated with New York, but she did spend the mid ’80s to the early aughts in San Diego as a professor at the University of San Diego. She also has ties to the Bay Area arts community. Moira Roth, who was a professor at Mills College, was a great friend and supporter of Faith. Faith actually got an honorary doctorate from Mills, so I think she does have connection to and resonance with California. I’m very excited that people will get to see [the show].

48 HILLS And here’s another big question. What do you think makes Ringgold’s work so powerful?

JANNA KEEGAN There’s an honesty and a vulnerability in her work. She puts so much of herself in her works that I do think they have a resonance that transcends the individual objects.

FAITH RINGGOLD: AMERICAN PEOPLE runs through November 27. de Young Museum, SF. Tickets and more info here.