Oscar-winning documentarian Laura Poitras used to live in San Francisco, where performance artist Mark Pauline was a neighbor and he and his Survival Research Laboratories often added explosions to the neighborhood ambience.

“We lived close to a fire station,” Poitras remembered during a recent video call. “They would explode something—they would be testing, like, their green slime—and we had to pretend that it didn’t happen when the fire truck would come in.”

Poitras has spent her career making her own kind of explosions. The filmmaker who studied avant-garde film at the San Francisco Art Institute has created an acclaimed body of documentaries, including Citizenfour (the one for which she won the Academy Award) about NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden and Risk, about WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange. Now, she’s back with All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (playing the Roxie Fri/23-Tue/28), only the second documentary to win the Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion.

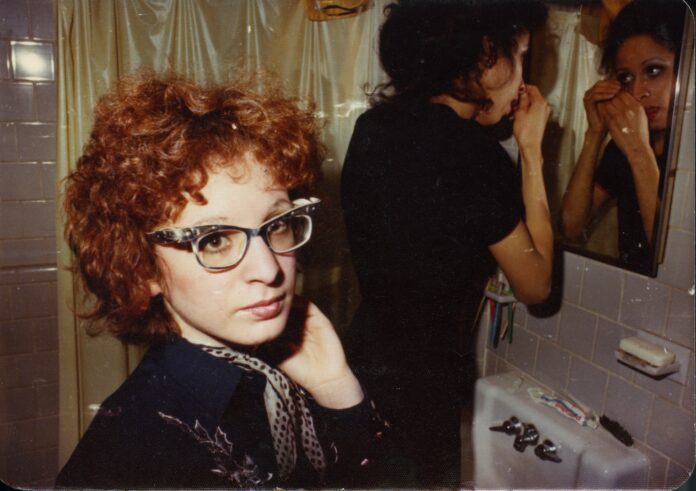

The film is a Rubik’s Cube of sorts, focused on photographer Nan Goldin. It documents her art and her life—but also on her work with Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (P.A.I.N.), the organization she founded to hold the Sackler family responsible for the Oxycontin addiction crisis created by the family’s company, Purdue Pharma. In particular, through a series of demonstrations and die-ins, the group protested museums art-washing the Sacklers’ blood money by accepting the family’s large donations and putting its name on their galleries.

Members of P.A.I.N., in fact, had already started filming the group’s actions before Poitras became involved in the project. The filmmaker had first been introduced to the photographer’s work when she studied avant-garde filmmaking at the San Francisco Art Institute. Now, she was invited to breakfast with Goldin, who explained that she was documenting P.A.I.N.’s activities and wanted to pick Poitras’ brain about producers. Eventually, Poitras was invited to join the film.

“I was really compelled by what she was doing, that Nan was using her leverage in the art world to take on the Sacklers,” Poitras says.

“That was the sort of initial hook for me. A more personal piece emerged once we started working together. She shared with me her piece “Sister Scenes” about her sister Barbara. That haunted me for days. We talked and she said she would be open to talking to me about Barbara. I was just haunted by the story, by a young woman in the 1950s who was institutionalized for being rebellious or being sexual, the tragedy of that story.

“I think the thing that really haunted me was… the family’s denialism and Nan’s complete rejection of that, which exists throughout her work. She tells a history of her life through her photographs that is on her terms, rejecting some of the narratives that come from the wider society. I was really interested in that.”

Goldin is, in fact, a producer on All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. Poitras had access to Goldin’s personal archive, including imagery from her and Barbara’s childhood. And over the period of a year-and-a-half, the filmmaker interviewed her subject, audio-only conversations. Once a rough cut of the film existed and shown to Goldin, Poitras did more interviews based on the photographer’s notes.

“There is no bullshit. Nan speaks in this very unfiltered way,” Poitras says. “For me, the heart of the film is that sense of honesty, in her photographs and the interviews, and the rawness.”

One thing Poitras wanted to make explicit were the parallels between the opioid crisis now and the AIDS pandemic that began 40 years ago and that was made so much worse by government and societal indifference at its onset. The methods that Golden and her P.A.I.N. cohorts employ are those she learned from ACT-UP when the LGBT community was fighting for its life.

“We always had merciless logic, from the beginning,” says Poitras. “We’re a society that destroys if you’re rebellious, outside, or sexual. The forces of society are destructive toward individuals who don’t conform but reward people like the Sacklers, who profit from people’s suffering and pain. This is a world that is cruel, that destroys the vulnerable.

“I knew from the very beginning that there must be a convergence between the overdose crisis and what happened in the ‘80s with the AIDS crisis, and that historical amnesia of the failure of the US to provide for its citizens. We don’t have healthcare in this country. We kind of blame people who are suffering. That’s all kind of repeating.

“I wanted to draw out that connection through Nan. Nan finds herself twice losing generations, and surviving that, and bearing witness, and not being quiet. I love that about Nan. She’s doesn’t stand by; she takes action… She’s on the right side of history and I wanted the film to bring that forward.”

In some ways, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed is a story of triumph. Art institutions have stripped the Sackler name from their buildings and severed their relationships with those modern pharma robber barons. But Poitras is not so sure.

“We get to see that and that’s a victory,” she says. “But there’s also complete impunity, right? The Sacklers are not charged with any crimes. That’s a horror story, that you can knowingly be responsible for that level of devastation and death and walk away.”

ALL THE BEAUTY AND THE BLOODSHED plays Roxie Theater, SF, Fri/23-Tue/28. More info here.