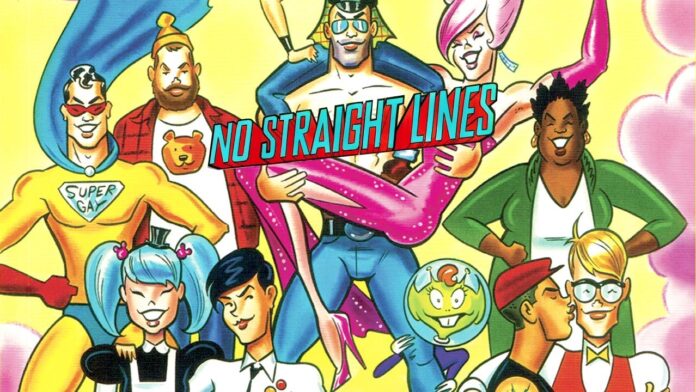

What do you do when you publish the first history of queer comics? Why, you turn around and make a movie of it, of course.

If only it were that easy. Ten years ago, local comics artist Justin Hall wrote the revelatory book No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics, which not only shed light on this essential, often erased history but also helped establish queer comics curriculums in art departments and schools. (A Fulbright scholar, Hall is now Chair of the Graduate Comics Program at California College of the Arts.)

“While I was finishing up the book, a friend came up to me in the gym and said, ‘We should make it into a movie!’ Well, 10 years and many, many twists and turns later, it’s finally out in the world,” Hall told with a laugh over the phone from Palm Springs, where he was taking a little Winter break-time by the pool.

The completed documentary, No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics will be debuting on PBS/KQED through its Independent Lens series, 10pm on KQED Mon/23, and will be streaming for free on its platform for three months. After that, PBS will host the film behind its paywall. Additionally, Fantagraphics Books is putting out a 10th anniversary edition of the No Straight Lines book with more material and an expanded introduction by Hall.

Once a DC Comics superhero-sidekick subtext or something only encountered in the “Adult” section of big city bookstores, queerness in comics is now fully acknowledged as a force that drove the development and popularity of cartoons as an art form. “The barrier to creating comics is so low that really anyone can do it,” Hall said. “All you need is a pen and paper and a photocopy machine. Which is why it particularly appeals to marginalized audiences, who don’t always have access to the means of art production.

“I’m going to have so much to write about for the new introduction,” the ever-buoyant Hall continued. “The reach of queer comics has completely changed. Before, our comics were extremely marginalized, and now they’re centered in the comics industry. It’s happened so fast. We’re finally being taken seriously, even outside of the insular world of queer media. Queer comics are winning Eisner Awards, queer comics characters are appearing in mainstream contexts like TV shows and movies.

“One of the most banned books in the US right now is Genderqueer, a graphic novel memoir by Maia Kobabe. It’s been practically on every newscast in the country. The list of top-selling graphic novels and comics is full of queer authors, queer stories. And it’s intersectional. There are queers of all colors, genders, and abilities making tremendous comics that are finding an audience. The mainstream world of superheroes is still mostly made by straight white men, but even that’s changing.”

The documentary pays homage to groundbreakers like Howard Cruse (who passed away during the film’s production), Mary Wings, Jen Camper, Rupert Kinnard, and Allison Bechdel, as well as delving into some of the struggles and rewards of telling your story to the world. “One of the hardest things when you work in a medium whose history has been erased, or has just never been told, is that every generation feels like it has to reinvent the wheel,” Hall said. “It can feel like there has never been anyone who has been like you because you don’t have access to that history.

“That’s a huge part of why we did No Straight Lines, to connect queer artists across generations. For instance, in the film a young Black comics artist Lawrence Lindell talks about how he discovered the work of Rupert Kinnard. I had taught him about Rupert’s existence when he was my student at CCA, and then we were able to put the two of them together on a panel of queer Black cartoonists at the Queers & Comics conference I hosted with Jennifer Camper. Both of them just lit up, Lawrence because he was meeting a pioneer making queer Black comics from so early on, and Rupert because he could see his work inspiring younger artists. Watching Lawrence describe discovering Rupert and his work is one of my favorite moments in the film.

“When I started my own comics career, I felt like I was in a vacuum. I didn’t know any other cartoonists, especially queer ones. I met my first fellow cartoonist when I was at a cafe and noticed another guy there had a Spidey Tracer, this arcane thing from the early Spiderman comics, tattooed on his arm. Now, none of my students have that problem. They can get their comics out and connect almost immediately to a supportive community online and in person.”

You can learn more about No Straight Lines playing on PBS here.