On Monday morning, I reached for my phone to turn my alarm off. I usually can expect a text from my mom with a photo of our dog, or an alert from my university that I got a grade back. Instead, I woke up to notifications on my lock screen from CNN, AP, NPR, the New York Times — every news app I have downloaded, as well as alerts from my police scanner.

I know what that means.

It was Nashville, this time. An elementary school. That was all I needed to know. I put my phone down and stared at the ceiling, wading through uncomfortably familiar feelings: the visceral hurt, numbed by repetition, the same way I’d felt for weeks after the breaking news from Uvalde. I tried to write something from the pit in my stomach then, but struggled for what to say from my perspective. I’ve never been in a school shooting, but every time one occurs, it consumes me.

I’m an individual of a generation touched by gun violence in an all-encompassing way. There are countless articles suggesting the proper way to approach the topic of school shootings with children. There are countless moments of insignificant theatrics following a mass shooting. There are kids who survive these tragedies becoming gun control activists before they become adults, because they have to. In conference rooms around the country, lockdown procedures are being once again elevated in severity, reiterating it’s our job as students and teachers to survive shootings, not the job of our elected officials to prevent them.

On Monday, I called some friends of mine from around the country to talk through what I couldn’t express. They aren’t activists, aren’t survivors, and aren’t experts — just the outermost seismic rings from the epicenter of gun violence in schools, where we still feel and grieve the impact. I asked my friends if I could share our conversations; they graciously said yes.

For context: I was born four years after Columbine, with the rest of the nationally designated lab rats for trial and error of active shooter protocol. When I started kindergarten in 2008, lockdowns were games: the teacher would draw the shades and turn out the lights, as we hid in a dark corner, giggling as we tried to stay quiet. Nothing more than hide and seek during the school day.

I was in fourth grade when Sandy Hook happened; that was when lockdowns became active shooter drills. My elementary school in east Tennessee spent hours and multiple days teaching us new active shooter protocols. We had to learn which alarm meant hide, and which alarm meant run. We had to learn how to outsmart a shooter.

Our teachers took us to the edge of campus and had us practice running away from the school. I don’t know how many of my classmates were aware of what we were doing or why, but I remember noticing a darker tone during lockdown drills. Even the teachers took it more seriously. I remember, year after year, the teachers struggle to explain to us why we were doing them.

My cousin Abby (22) grew up in Paducah, Kentucky, and is studying to be a social worker. She lives in Louisville with her friends Payden (22) and Sara (20).

Conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

SARA: My little sister’s going to be a teacher, and she’s debating where she wants to work, because school shootings are so high. Just like, “Do I really want to do this? I love teaching, and love education, but do I want to possibly give my life for it?”

ABBY: And protect 20-plus kids at a time.

SARA: The safety protocols — they teach that now, in education.

ABBY: And there’s only so much you can do when someone comes in with a fucking automatic rifle.

JJ: You guys live in one of the states where there’s been dialogue around arming teachers. No right or wrong answers, how do you feel about that?

All three look at each other and laugh.

PAYDEN: I honestly, just, I hate guns. It’s just who I am. I’m open to hearing what other people have to say about it. I just don’t think arming teachers is the best option.

ABBY: You can’t trust anybody.

SARA: (agreeing) No.

ABBY: There are teachers who hit students when they’re just being a little bit difficult.

PAYDEN: Also, the possibility of a student getting ahold of the teacher’s weapon?

SARA: You can’t solve something by adding more of it.

PAYDEN: Exactly.

I went to school with Brendan (20) in northern Virginia for five years. He’s currently a sophomore at the University of Pittsburgh, and most recently worked on the US Senate campaign for John Fetterman as an intern.

JJ: [Mutual friend] said that you had a lockdown yesterday.

BRENDAN: Yeah.

JJ: What happened?

BRENDAN: We got the text — the Pitt emergency alerts — we got a text saying, “report of a critical incident at Central Catholic, please avoid the area.” That’s down the street from campus. And that was at 10:30. There were screenshots of reports of a shooter going around in group chats. The news reported an active shooter with six people shot in Catholic High School. Ten minutes later, we got a second alert: “Campus is on lockdown until incident at Catholic is resolved.” Yeah. So I call my parents, tell them, “I’m on upper campus, I’m good, but I want to let you know before you see it on the news.” Then there were reports of other high schools in the area getting active shooter calls. And that led to a suspicion that it was a hoax. And it was a planned attack from scammers, or dark net, or whoever — some sick people, calling in shooting reports to these high schools three days after the shooting in Nashville.

JJ: These real high schools that are now having their real active shooter alarms go off for hours.

BRENDAN: Yeah. 11:19, we get the text the university is reopened. I saw on people’s stories, SWAT teams rolling up, news helicopters were circling — people were really freaked out. Really freaked out.

JJ: How does it feel today?

BRENDAN: I mean, we had a conversation in my PR class today about the university’s response to it. They sent out an email saying, “We hope everyone’s okay,” and that was it. From some vice president of something who we’d never heard of. So that was reassuring, right? I think it was really weird that the high school students went back to school. They immediately went back to school. They said, we’re keeping them there, no parents should come pick them up. Why would you do that?

JJ: That’s what happened to us.

BRENDAN: Yeah. Yeah. But they gave us hot chocolate the next day, so it’s all good.

JJ: It’s all fine.

BRENDAN: Hot chocolate and cookies make up for everything.

JJ: Next spending bill.

BRENDAN: Honestly.

JJ: So we were in our first year of high school when Parkland happened, right?

BRENDAN: Yeah.

JJ: And a few months before Parkland happened, the active shooter alarms went off at our high school. And it turned out to be an accident, there was nothing actually wrong. But for about 15 minutes, the active shooter alarm was on and nobody knew what was happening.

BRENDAN: I was in the chemistry rooms. I have a now funny story about this, where — you remember how they taught us to barricade the door with desks and stuff?

JJ: Yeah.

BRENDAN: Yeah, we barricaded the door and then realized it opened out.

We both laugh, for some reason.

BRENDAN: People in the art wing ran onto the roof. People in the lower science wing got out and were running across the soccer field to get off campus. And then, after all that, they just made us all go back to class.

JJ: What I remember about what the school did afterwards, was the assembly we had where our dean of students walked us through how to run in a zig-zag while the baseball team threw ping pong balls at them, that were supposed to be bullets. To see how they’d get hit less when they ran in a zig-zag. Except they still got hit.

BRENDAN: Yeah. (He laughs.) Yeah.

JJ: As someone who works in politics, you know, with everything we just talked about, everything we experienced growing up, when you see discussions about safety in school revolving around what they’re learning, and parent’s choice, and gender identity…

BRENDAN: What’s the phrase? Hugs and prayers?

JJ: Thoughts and prayers.

BRENDAN: Yeah, that’s all I have to say. Thoughts and prayers. And the new congressman in Nashville’s district [Rep. Andrew Ogles] with the rifles in his Christmas card — that’s some stupid shit. Can I curse in this?

JJ: I don’t care. We’re far past cursing.

BRENDAN: That was some stupid shit.

When we were 14-year-old first-year students, I was taking a math test on a Thursday morning, and leapt out of my chair at the piercing two-toned alarm and blue emergency lights flaring. My heart fell to the floor when I registered what was happening. Our system had a recorded message that played intermittently between the awful sound of the alarm: “This is a lockdown emergency. Please take shelter immediately and follow all lockdown procedures.This is not a drill.” I remember those words very clearly.

We had been trained for that moment, since kindergarten. There was no screaming — the searing panic was silent. We frantically used our desks to barricade our classroom door, wincing when metal clanged against metal, before scrambling to a corner of the room, sitting as tightly packed as possible.

Our teacher took the pair of scissors from his desk and stood beside the door, staring at us crouching in the corner, trying to cry silently. Half-finished tests were strewn and stepped-on around the room. I texted my mom in the midst of a panic attack so severe I had vertigo. I told her all I knew at the time: our lockdown alarms were on, and I loved her.

It lasted maybe ten minutes, until our dean of students came on the loudspeaker to announce it had been a mistake. There was no active shooter. Classes would resume as normal. And they did.

My classmates and I were in tears and shock. We ran into the hallway to find our friends and fall apart in each other’s arms. I went to the nearest bathroom and threw up.

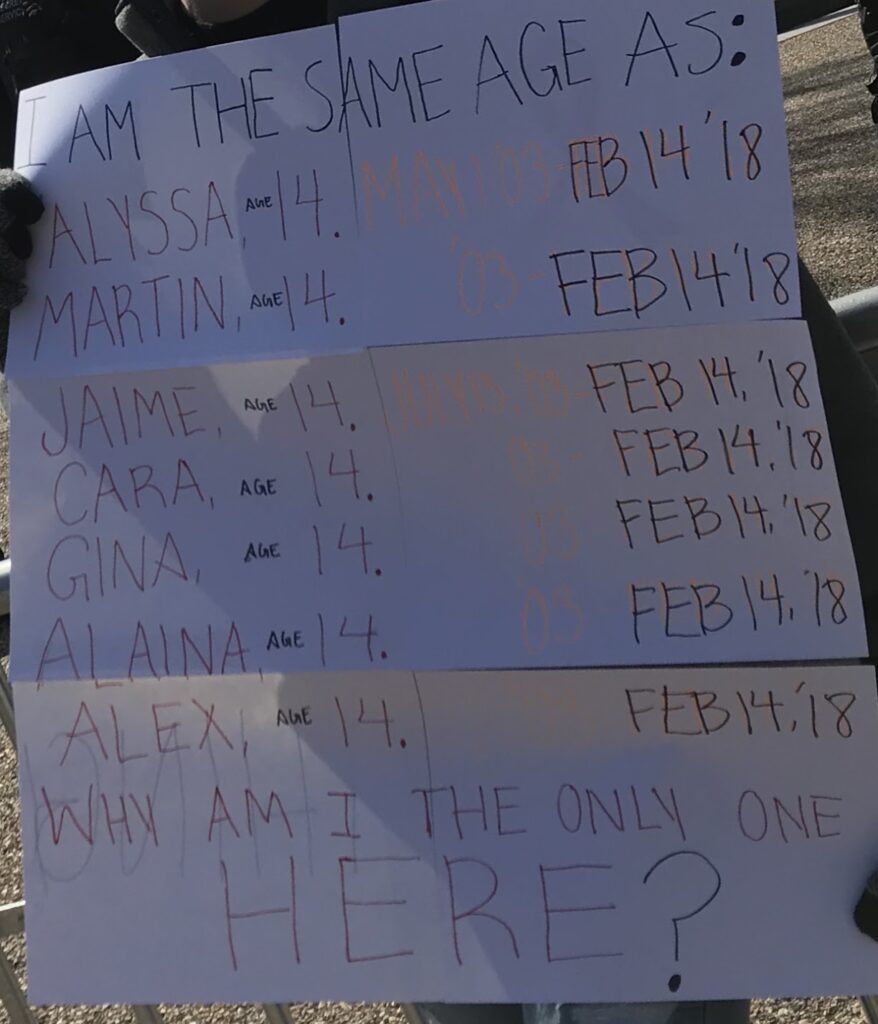

Less than three months later, a shooter walked into Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School and killed 17 people. Most of the kids murdered were 14 years old.

My friend Melissa (20) grew up in Miami. She’s studying political science and philosophy, and plans to become a lawyer.

JJ: Do you remember anything about Parkland?

MELISSA: Yeah, I lost a friend to Parkland.

JJ: What?

MELISSA: Yeah.

JJ: Wow. I’m so sorry.

MELISSA: That’s okay. That’s when it became real. But… yeah. We can talk about that, if you want. My whole thesis my first year was on gun control versus gun protection.

JJ: How did you find out about Parkland?

MELISSA: It happened on Valentine’s Day. We all got locked down. I went to a Catholic school, about half an hour from Parkland. My best friend lives in Parkland. And all the schools in Miami got shut down in case of a copycat, and the next day a lot of people weren’t allowed to go to school because of the copycat method, where shooters replicate other shooters.

Yeah, it was announced over the speakers. All of Parkland was shut down. I went straight to [her friend from Parkland’s] classroom. All of the traffic was closed in Parkland, so she came home with me — she lived right across from the high school in Parkland. She lost five friends. Later that week, we only had a 17- second moment of silence, and a fake mass. That whole time [her friend] was having a panic attack, it was really rough on her.

——

MELISSA: I didn’t march or anything. I explained my feelings through papers and academic work. Not that I think that’s more productive, or beneficial, or anything.

JJ: It’s what you did.

MELISSA: Yeah, it’s— I’m really good at writing, and people write because nobody listens. No matter how many people are out screaming, nobody’s gonna listen, or no one has. Trayvon Martin got shot, and we got the Stand Your Ground law in Florida as a response. So… yeah. Gun problems have never diminished. It’s really depressing.

——

MELISSA: After Parkland, we all got a bunch of training, and that’s when the topic of whether teachers should have guns in the classroom came up.

There’s a long pause.

JJ: How are you feeling right now?

MELISSA: (Laughing) A little anxious.

JJ: I know. I’m so sorry. Thank you for doing this.

MELISSA: Of course.

JJ: Other than Parkland, did the active shooter alarms ever go off?

MELISSA: The day after, we were locked down for three hours. It happened to a lot of schools, the ones that even had school that day.

JJ: What were you feeling in that three hours?

MELISSA: We were over it. We were pissed. We didn’t even want to be in school. We were scared to be in school — a lot of people didn’t even come. So to make us sit in angst for three hours, I think, was so ridiculous. And then we had to wear clear book bags for a while, until people just stopped doing it. There was security, metal detectors. We’d have to wait in line for an hour. I think that happened for a lot of schools. They started selling bulletproof backpacks, backpacks with kevlar padding in them.

My friend Maddy (20) grew up in Wisconsin, and is a graduate of culinary school.

JJ: I’m assuming you remember Parkland?

MADDY: (sighs) Yes. Yes I do. I remember it because kids at our school would start making threats for attention. We got bomb threats, like, every month, probably. It just kept getting worse.

JJ: I remember you talking about that.

MADDY: It was insane.

JJ: Did you ever go into lockdown?

MADDY: Yes, once, in high school. We went into a big-boy lockdown. Someone was in the school with a gun, but they caught him before he could start shooting. We were in lockdown early in the morning, and we were having an assembly that afternoon, which is where the guy had been planning to shoot us up. But they caught him, so they said, “it’s okay, GO TO THE ASSEMBLY!”

We both laugh in disbelief.

MADDY: I fuckin,’ I hid in a practice room. I couldn’t do it.

JJ: How did you feel?

MADDY: Oh, fucking terrified. All the time.

JJ: Yeah, I don’t know why I asked.

MADDY: I went to such a massive high school, too, that it could be anybody — the amount of suicides at our school made me anxious, because usually shootings happen because the person holds some sort of resentment to the building itself or the people in the building, and they’ll take it out either on themselves or on the other people. So just the amount of kids who were killing themselves, I was like, “How many people are going to take it out in a different way?”

JJ: Do you remember finding out about Uvalde?

MADDY: Yeah. Holy shit. That was when I became conscious as a person. It kind of hit me how unbelievably serious it was. I cried, hard, watching the interviews, seeing the kids. How could anyone do that? I don’t get it. I don’t get why guns are more important than that. I have an issue with people who revert back to the constitution. I’m not saying nobody can have a gun! That’s not what we’re saying, we’re asking for stricter regulation laws to prevent people who do these things from getting the gun.

JJ: That’s the part I can not understand. For the fucking life of me.

MADDY: Right. There just needs to be a safety process. And if you’re a good person and good gun owner, you wouldn’t care about that. Because it wouldn’t affect you. If you have such an issue with going through a further process of getting a gun, you shouldn’t have one.

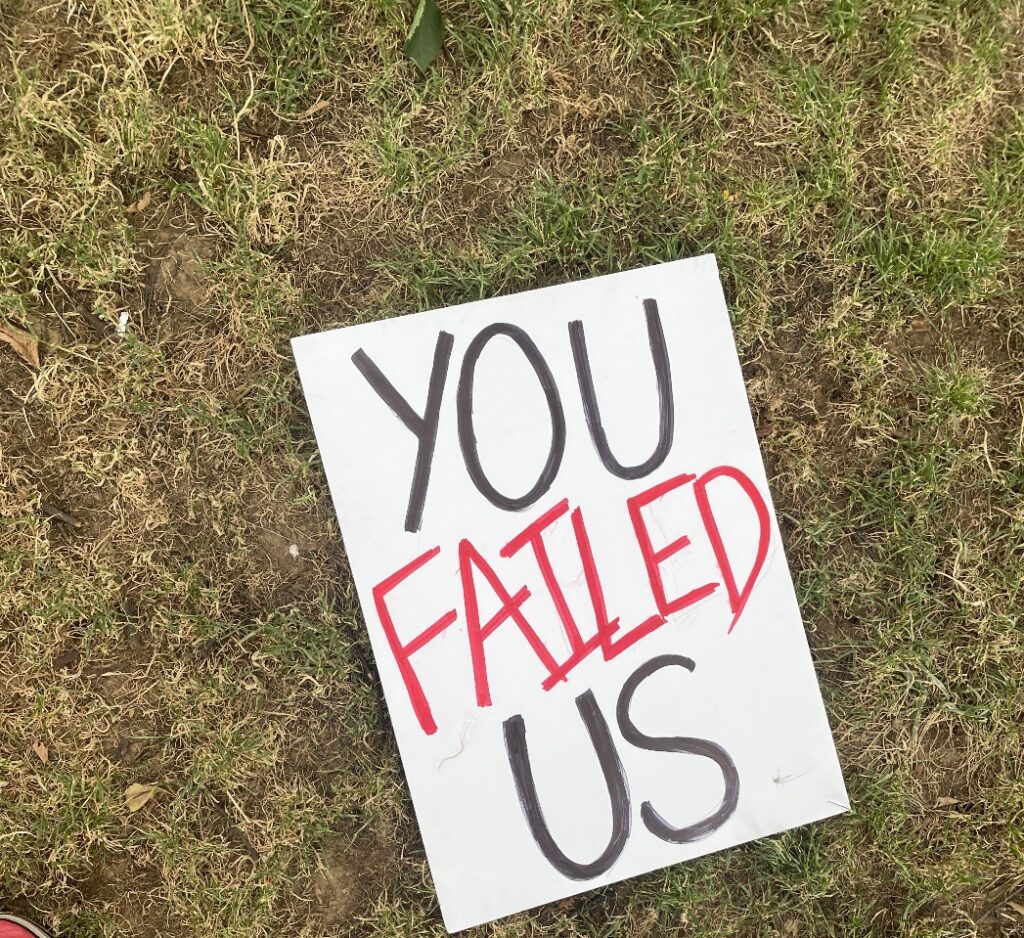

I went to the first March For Our Lives rally the month after Parkland because I needed help understanding why I felt devastated. The Parkland survivors gave us a gift that day; my generation gathered by the millions across the country to look each other in the eye and feel less alone as we grappled with the totality of our grief. After Sandy Hook, adults debated on behalf of us, and the burden of systemic change once again fell to how we were trained for in-school combat. For those of us who grew up that way, Parkland was agonizing—and our first chance to speak for ourselves.

BRENDAN: I’m so desensitized to this stuff. I saw Nashville on the news, and I thought, “damn, another one.” When I saw the notification yesterday, I thought, “damn, another one.” I’m so, so, so desensitized to it because it’s happened so much.

There’s a brief pause.

JJ: What’s really interesting about everyone I’ve talked to is that everyone has said something like that — “I’m really desensitized” — and yet it’s still so personal to them.

BRENDAN: I’m sorry that I can’t feel the despair that I should.

JJ: Did you at one point?

BRENDAN: Oh, yeah. Parkland— Parkland was the last one I felt.

JJ: Parkland shattered me. I went to March for our Lives the month after. I went to the one last summer, too, and there was a scare there. Someone yelled “I have a gun” during the moment of silence for Uvalde. We all ran.

BRENDAN: Jesus.

I remember, viscerally, how our lives changed as grade school kids after the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012. With Parkland and March for our Lives, we finally had an opportunity to feel like what we’d been through as a generation could result in change. It was a glimmer of hope, that we would be the one and only lockdown generation. If we could protect our little siblings from going through what we did, maybe this could make some kind of sense.

When I turned on CNN to watch the breaking news from Uvalde, I sat on the floor and cried until I couldn’t breathe.

MELISSA: I got an unproductive anger from [Uvalde]. It’s no shocker, the one from Tennessee this past week — Tennessee in February passed a fucking law against minors at drag shows and restrictions, they’re using Cohen v. California to claim that it’s for the protection of children, but the number one leading cause of death for children is guns. In the United States. And in Florida. And any state you can think of. That was my main argument in class the other day, was that their interest is not protecting their children, but that their children don’t turn out gay. God forbid their children turn out gay.

About 75 minutes into March For Our Lives 2022, we had a moment of silence for Uvalde. The National Mall fell silent for a few seconds, broken by indistinct shouting from somewhere in the crowd. People’s heads around me snapped towards the sound, as he continued yelling. All I heard was “gun,” and that was all I needed to hear.

Everyone dropped what they were holding and ran. Parents were dragging their toddlers. People abandoned their bikes and dove headfirst over police barriers. Adrenaline was clouding my attempt to assess whether I should lock myself in a porta potty or keep running until I reached Virginia. This was all maybe ten seconds, until a woman rushed to the microphone to firmly reassure us there was no active shooter. And the rally continued.

My friend Raeghan (20) grew up in both Nashville and Arkansas.

RAEGHAN: The one this week in Nashville, that school was a feeder to my high school. It was in the backyard of a lot of friends’ houses.

JJ: How did you feel when you found out about it?

RAEGHAN: That one … was different. High schools my mom taught at were on lockdown, because they were around the block. The school day ends at 2:40, they couldn’t leave the building until 4:00 because of everything happening. It’s a lot more personal.

I ask this question genuinely:

JJ: You have any hope this is gonna change?

RAEGHAN: I don’t think so. Especially with this one that just happened, it’s gonna go away from gun control and toward the anti-trans laws in Tennessee. I think they’re gonna skip over gun control completely and go to anti-trans rhetoric.

JJ: It’s already done that.

RAEGHAN: It’s already done that. That Marjorie Taylor Greene tweet talking about hormones going through their body, and that blames — what? Every man has those hormones.

She’s referring to the congresswoman tweeting, “How much hormones like testosterone and medications for mental illness was the transgender Nashville shooter taking? Everyone can stop blaming the guns now.” Her Twitter account has since been suspended.

JJ: I always feel a numbed anger after one of these, but it hurts this time to see how immediately it became a scapegoat to anti-trans legislation in Tennessee.

RAEGHAN: (nodding) There’s so many layers of devastation to this one.

We are among the luckiest American kids of the last 20 years; in sharing these awful experiences, I hope to only emphasize that.

It would be easy to say I don’t know what I’m talking about. I get it — it’s fair. I’m lucky because I went to schools with money to form intricate lockdown procedures, because I didn’t live in neighborhoods with overwhelming gun violence, because I got to wait to learn about surviving it until it was a national problem. I’m lucky because the music festivals, nightclubs, and religious ceremonies I’ve attended weren’t the ones a gunman decided to target.

If nothing else, I hope it comes across, knowing that I’ve experienced the least of it, that gun violence and inaction on addressing it remains deeply personal to me, to my friends, and to millions of others who’ve grown up alongside us. Lockdowns are a constant reminder. And when a tragedy isn’t prevented and results in a mass casualty event, getting the breaking news on my phone stops me in my tracks, full of something I don’t know how, or when, or where to express. Secondhand devastation for kids I don’t know. Firsthand sadness for their classmates’ generation, too young to hold the burden of change that I know will be once again passed to them.

JJ Lansing is a Media Studies major at the University of San Francisco.