In the 1960s filmmaking became more of a truly international medium than before—co-productions between different countries grew much more common, Hollywood stepped up filming overseas (where it was generally cheaper), and foreign films achieved a peak, if still modest, share of even the US market. The borders of stardom became more permeable as well, in part because the prior decade had seen French Brigitte Bardot and Italian Sophia Loren become international sensations to rival Marilyn Monroe.

That lead to an explosion of screen Eurobabes in a decade where censorship standards were easing, allowing for more skin and innuendo. The Sexual Revolution was then very much a male-gaze phenomenon at the movies, personified by James Bond and his imitators—globe-trotting bon vivants who magnetized bikini-clad sexpots wherever they waved their, er, gun. Among the more prominent such bombshells launched during the era were Ursula Andress (from Switzerland), Elke Sommer (Germany), Capucine (France), Marisa Mell (Austria), Ewa Aulin (Sweden), and many more, drafted from as far afield as Israel, Turkey and Yugoslavia. (Non-white sex symbols were not much in evidence onscreen until the next decade.)

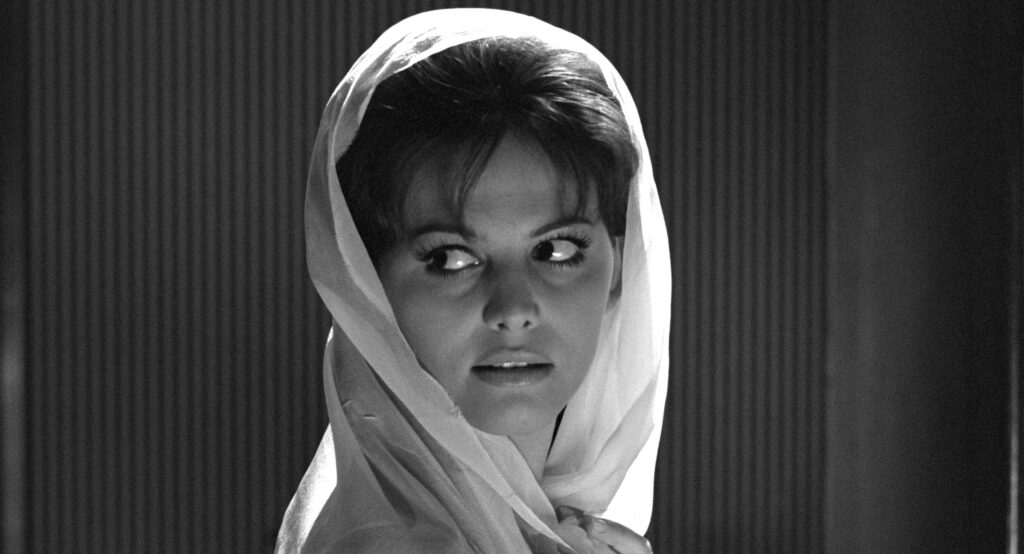

The lower in the pecking order, the likelier such women were to get roles that were little more than decorative, often in movies verging on exploitation. But a few got to prove themselves capable of much more, including the subject of current BAMPFA series “Claudia Cardinale Once Upon a Time,” which runs through July 22.

Claude Josephine Rose Cardinale was born in 1938 to Sicilian-emigre parents in Tunis, when Tunisia was under French rule; multilingual from early on, she did not actually learn to speak Italian until she began being cast in Italian movies. (And even then, she was for a long time dubbed by others—her voice was initially considered too hoarse for her image.) A film career came about in a way typical for actresses of the era: She won a beauty contest, winning the attention of producers, including eventual first husband Franco Cristaldi.

Despite a lack of any relevant training, her acting from the start had an appealing naturalism, particularly in contrast to the many stony screen beauties of that era. Plus, she was blessed with extraordinary luck in projects. Her 1958 debut, Tunisia-shot Goha, won a prize at Cannes and starred a very young Omar Sharif. The same year she had another supporting role in Mario Monicelli’s lighthearted crime carper Big Deal On Madonna Street, a huge hit that greatly raised the profile of all participants. Nonetheless, her rise to real stardom was not immediate. The earliest title in the BAMPFA series, Pietro Germi’s 1959 The Facts of Murder (playing Thu/15), has her in another ostensibly supporting if key role—offscreen for most of its two hours, yet prominent at this police investigation narrative’s beginning and end.

But she attracted the interest of important directors, and the relative modesty of her roles for Visconti (Rocco and His Brothers, The Leopard) or Fellini (in 8 1/2) did not diminish the prestige of being involved in those films. Meanwhile, she was getting leads in smaller but interesting films by other distinctive talents: A flighty type exasperating a humorless political agitator (West Side Story’s George Chakiris) in the 1963 Bebo’s Girl, which like costume epic The Leopard played last weekend; a showgirl abandoned by one lover but pursued by his little brother in Valerio Zurlini’s 1961 The Girl With a Suitcase; a titular figure trapped by her aristocratic family’s heavy emotional baggage, which encompass everything from Auschwitz to incest, madness, and anti-Semitism, in Visconti’s 1965 Sandra. Lesser-known are two compellingly moody tales of romantic obsession from director Marco Bolognini, where her self-possessed figures madden would-be possessors Jean-Paul Belmondo (1961’s La Viaccia) and Anthony Franciosa (the next year’s Senilita).

While often playing a male protagonist’s object of desire, Cardinale lent these characters considerable differentiation in looks and manner. You might argue she was not a truly great screen actor. Still, she was no slouch—she had energy, craft and intelligence. However, her natural beauty and warmth (both of which seemed the more striking the less fussed-over she looked) drew many filmmakers to present her simply as a sort of impossibly ripe peach, drooled over by all male-kind. That’s pretty much the joke in Antonio Pietrangeli’s 1964 sex comedy The Magnificent Cuckold: Because he’s cheated himself, Ugo Tognazzi cannot believe his adoring wife is faithful—after all, she’s Claudia Cardinale! Every man wants her!

Around the same time she inevitably entered English-language cinema, starting with the original Pink Panther (1963), and including movies with John Wayne, Rod Steiger, Rock Hudson, Anthony Quinn, Burt Lancaster, and Tony Curtis. Most of these were uninspired popcorn fodder in which she served as little more than eye candy.

Probably the peak of her career in the international mainstream was Sergio Leone’s 1968 epic Once Upon a Time in the West, in which—top-billed above Henry Fonda and Charles Bronson—she played the only truly dimensionalized female character in that director’s ultra-masculine oeuvre. It provides an endpoint to the BAMPFA series, though Cardinale hardly slowed down, even if dissatisfaction with her Hollywood sojourn overall meant fewer English-language productions going forward.

Instead, she knuckled down as a star of European prestige projects for both the big and small screen, picking up numerous awards en route. Indeed, much of her best work seems to have been done well after she’d basically disappeared from American consciousness, with an occasional exception like Herzog’s 1982 Fitzcarraldo. She appears to remain at least sporadically active at age 85—the most recent film in which she appeared was released just last year.

“Claudia Cardinale Once Upon a Time” continues at Berkeley’s BAMPFA through July 22. For complete program and schedule info, more info here.

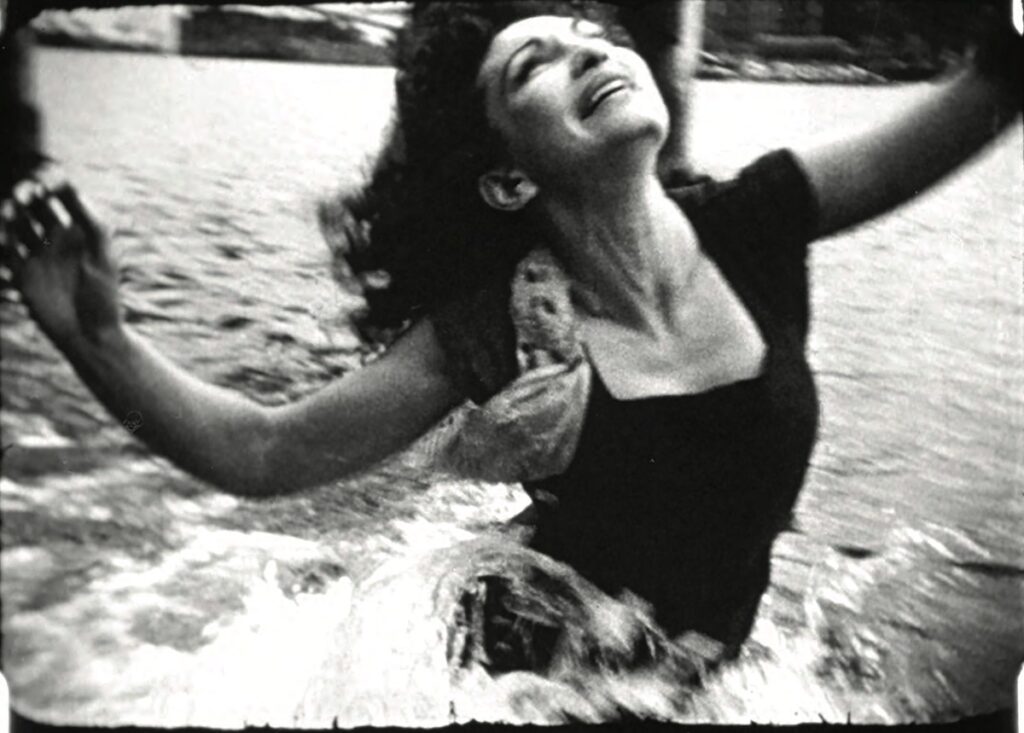

A very different figure of both glamour and artistic adventurousness is the subject of a San Francisco Cinematheque evening at Gray Area this Sun/18. Maya Deren: Choreographed for the Camera is occasioned by the publication of Mark Alice Durant’s same-titled book, apparently the first full print biography of the legendary experimental filmmaker. A Ukrainian emigre (her Jewish family fled pogroms in 1922), child prodigy, teenage Trotskyist, and participant in both East and West Coast avant-gardes, she worked in many media—including dance, photography, poetry, and anthropological research.

But it is a small body of films (even fewer of them officially completed) for which she is remembered. Three of them will be shown at Grey Area: Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), At Land (1944) and Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946). While the latter is more overtly choreographic in emphasis, all remain remarkable, unprecedented translations of dream logic onto film, their imagery making time and space behave in ways that seem natural in subconscious thought.

Often her own visually arresting, dramatically intense onscreen protagonist, Deren conveys a sense of entrapment as a quintessentially female condition—her presence is often oppositional, threatened or excluded, by individual men (including then-husband/collaborator Alexander Hammid) or by an implied society in general.

While their impact has perhaps been diluted by decades of imitation, these surreal films remain singular achievements, their influence impossible to overestimate. They also offer moving Rorschach blots of a very complicated personality (one extinguished in 1961, at age 44) that Durant’s book will surely help elucidate. For more info on the Cinematheque event, more info here.

The haunted, hunted feel Deren communicates in her best-known works might seem relatable to the title character in Blue Jean, writer-director Georgia Oakley’s debut feature. Jean (Rosy McEwen) is a 30-ish Phys Ed teacher at a Newcastle secondary school in England’s industrial northeast. It’s 1988, and the air is thick with Thatcherism, including a lot of anti-LGBTQ rhetoric. This is painful to Jean, who has recently come out (we belatedly discover she was in a heterosexual marriage until fairly recently)—albeit only to herself and within the local lesbian community. She’s less forthcoming so far with family members, and must stay closeted at work, where she could easily be fired for simply being a “known” gay person whose job requires presence in the girls’ locker room and so forth.

Not very understanding of the pressures she’s under is newly acquired lover Viv (Kerrie Hayes), a very butch, “out” personality who lives in a women’s commune and does not see the point of anyone denying their identity anywhere. Then there’s 15-year-old student Lois (Lucy Halliday), whom Jean encourages to try out for the girls’ soccer team. But, perceived as “different,” she’s bullied there, and in recognizing Jean as a potential lesbian role model, expects a degree of support her teacher is too terrified of exposure to provide.

This expertly tuned drama arrives at a well-earned hopeful resolution. But it’s largely concerned with prejudice and fear—the things Jean must eventually face down in order to claim her own new life. It’s a nervous-making film, especially if you’ve ever experienced the kind of social or workplace paranoia our protagonist does here. Unpleasant as it is at times, however, Blue Jean is an excellent first feature, one worth playing hooky from Frameline to catch at the Opera Plaza, where it opens this Fri/16.