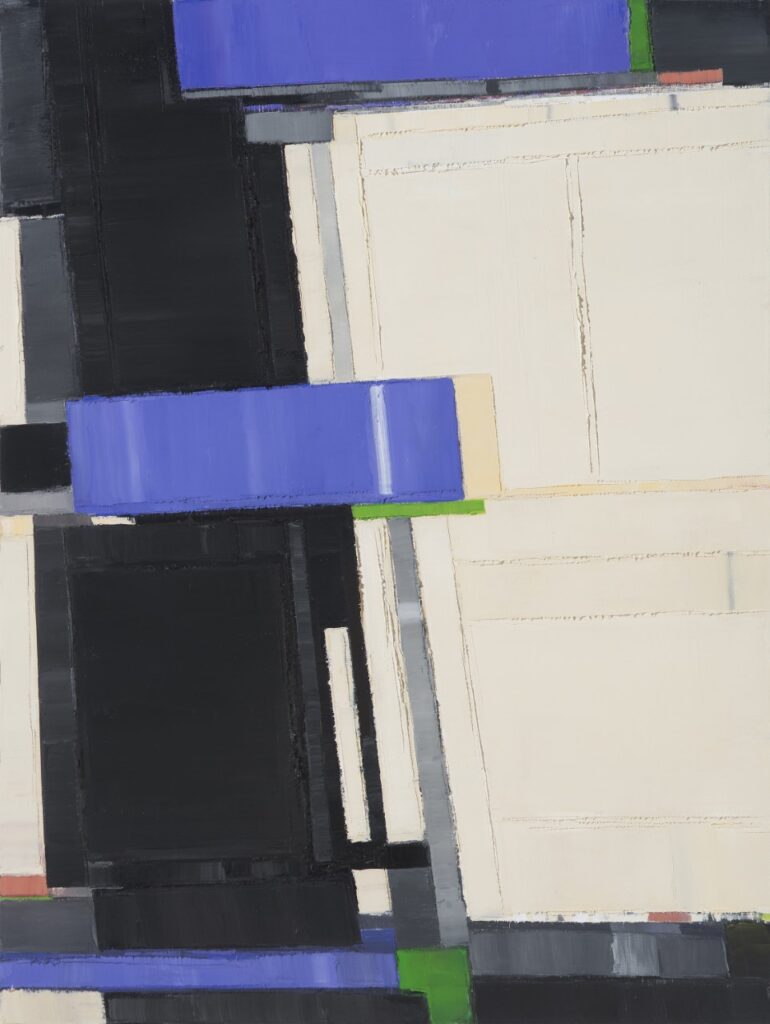

Artist Maya Kabat delights in the mazes and puzzles that are created in urban environments—the checkerboards of roads and the tangled mess of freeways. Equally drawn to the patterns that nature presents, she is fascinated with the materiality and architecture both provide. Kabat is not a landscape painter by traditional definition, but her keen eye for the subject is present in the abstract.

“I love paths through the woods, the way weeds push through cement and the reminders that we can’t escape nature,” Kabat told 48hills. “It’s about how control and chaos run up against each other.”

Born in Portland, Oregon, Kabat completed her BA in Anthropology and Art History (1993) at Oberlin College in Ohio. After floating around the East Coast, Kabat landed in California for graduate school at UC Davis (MFA, 2000).

“When I was 15, I came to San Francisco with my mother for a week and had so many wonderful memories of walking through the city in bright, glorious sun. And I have family in Berkeley, so it just made sense for me to come here,” she said.

Since childhood, Kabat has made things with her hands, particularly with fiber and cloth, which she learned from her grandmother. She recalls that her sense of touch has always been extremely sensitive. As an adult, Kabat didn’t consider herself an artist, but recognized what was missing: a desire to create things, but more intentionally.

“Once I started making again, I just kept following those interests. I have always been drawn to textiles and thread. This through line seems to be very important to me as I look back. Understanding the world through texture is a big part of what drives me to make art and why I choose to paint the way I do,” Kabat said.

Quilt-making was the medium that first really inspired her after attending a show in Ohio that blew her away. The intricacies, freedom and creativity resonated deeply. It was the Gees Bend Quiltmakers, a remote Black community of artists on the Alabama River, that became a particular inspiration for her.

“I loved their improvisational way of working, their use of color and their approach to that medium. I take that with me in my work today,” she said.

The path to paint began with a mentorship with a quilt-maker in upstate New York after college. In that process, she realized how much she really loved the interaction of colors, but ultimately found quilt-making limiting. She started to paint as a way to learn more about color, while also taking printmaking, collage, and drawing classes to build her skills. It was then that she decided on a small graduate program at UC Davis that focused on Fiber.

“I spent my time there knitting sculptures and making sewn fabric painting/collages. It was a fabulous, intensive two years,” she said.

After taking six months off to recalibrate, Kabat gravitated to painting because of the immediacy of the medium. She could work faster with it in her smaller space than with fiber works, so painting just made more sense.

Her large-scale, highly textured oil paintings connect to her formative years, whether depicting urban or rural landscapes on a micro or macroscopic level. Time spent on the Oregon coast as well as hours spent wandering the streets of downtown Portland both created a sense of place that she is always trying to recapture. Growing up in the 1970s and 80s, Kabat was left very much on her own to explore and she feels equally at home in big cities or in the woods and by the ocean.

As for artists who inspire, Kabat lists Louise Bourgeois, Howardena Pindell, Jay Defeo, and Eve Hesse, as women deeply invested in their materials and the textural meaning and potential of those materials, a natural resonance in her own work.

Kabat has a home studio in a small building behind her North Berkeley house with just one skylight but lots of wall space and good ventilation. She does all of her oil painting there as it’s private and she has complete control over the environment. She has a second, shared studio at The Dome in Oakland, established in 1976 by groundbreaking artists Anne and Peter Voulkos, now home to numerous artists. It’s a huge space with a rollup door in a large warehouse and Kabat uses the space primarily for storage and non-toxic prep work, experimental works on paper and fabric, meetings and studio visits.

“My painting days start by 11am. I paint ala prima, which means I can only work on the paintings if the paint is really wet. You would be surprised how fast oil paint gets tacky, especially in the summer,” she said. “So, when I start a painting, I pretty much have to finish it in one go.”

Kabat does small studies for larger works to map things out in advance, sometimes applying an under-paint before diving in with thicker paint. Between these two methods, she is able to block and determine the palette before committing to the piece. She’s chasing the light, as she feels it is necessary and optimal for her process, working in four to eight hours sessions.

“I can get pretty fussy when I am finishing up a painting, but I have learned that at a certain point the freshness can get lost. At the same time, paintings take time to massage and develop into something more than just a few dynamic, gestural marks,” she said.

Kabat says she’s gone through different phases with her work, describing it as an experimentation in detours and tangents. Exploring her materials in depth, once something catches, she goes deep into all facets of it.

Around 2006, she discovered the tools builders use for applying drywall compounds. The potential to really slab on thick paint and create densely textured areas was a revelation for the artist. After discovering this method, her work has ebbed and flowed a lot between controlled and careful works to looser, more painterly ones.

“I am always trying to find the balance between containment and chaos, improvisation and control,” Kabat said.

As the threat of natural events are constant realities in California, Kabat is endlessly fascinated with the way nature pushes in and disrupts things but also informs and shapes our urban reality in ways we don’t necessarily notice.

“We cover up nature. We bury our creeks and water ways. We pretend that earthquakes and fires aren’t going to happen or affect the intricate infrastructures that support our daily lives. I find all of this emotionally thrilling and very visually interesting, so that’s the track I have been following for some time now. From a bunch of different angles,” she said.

From a philosophical place, Kabat shares a sense of duty in sharing this awareness with others.

“My work is very much about the haptic and the physical, material realities of our world. As we lose more and more of ourselves to screens and meta reality, I feel more and more strongly that the purpose of my work is to ground the viewer in their bodies and bring us all back to a world that involves our sense of touch,” she said.

She has also realized that she can’t do work about the land without considering the history, settlement, and internalized sadness of living on it.

“Who was living here before and how did they live? What did this landscape look like before I arrived? How did humans think about land before settler colonialism and how can we live more sustainably? I haven’t figured out any clear answers, but I am thinking, reading, and studying a lot about it. I am particularly interested in the ways in which human activity can benefit other living things rather than destroy them,” she said.

Kabat has been working on different bodies of work for two solo exhibitions. The first, “Super Spatial, Los Angeles,” at the Los Angeles Art Association Gallery 825, opening in late summer, focuses on the urban landscape of Los Angeles and the hidden natural forces and infrastructures that simultaneously support and threaten us. The second show this fall at SLATE Contemporary Gallery in Oakland, is in development as a series of “vertiginous landscapes” that reflect precarity and the sense of touch in particular.

Maya Kabat hopes her work offers a rich and compelling alternative to technological dislocation for viewers to get lost in color, texture and interrelationships, and come back into their bodies. She furthers her own inquiries as a docent of Tilden Park Botanic Garden in Berkeley and studies into the Ohlone and Tongva peoples and the history of the settlement of California.

“I hope my work shows the deep richness of the places where we live and the things that go unseen, whether that be the infrastructures that support our lives, hidden or forgotten histories, or a sense of texture that physically connects us to the world around us,” she said.

For more information, visit her website at mayakabat.com and on Instagram.