In the glorious and probing exhibition Elegies: Still Lives in Contemporary Art (through August 21 at the Museum of African Diaspora), independent curator Monique Long’s poignant title mixes the lyrical mourning for the deceased with a haunting stillness, where the lack of motion alludes to the French translation of still life as nature morte—dead nature. In Long’s rich curatorial framework, the exhibition profoundly reverberates with innumerable traumas within Black communities, while also creating an expansive dialogue for beauty, jubilance, and banality. In particular, William Villalongo and Devan Shimoyama present works that symbolically balance the threads of life and death with sumptuousness and poetry.

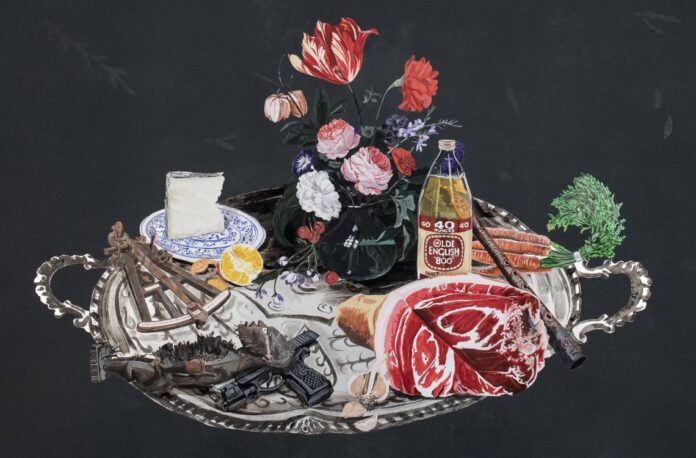

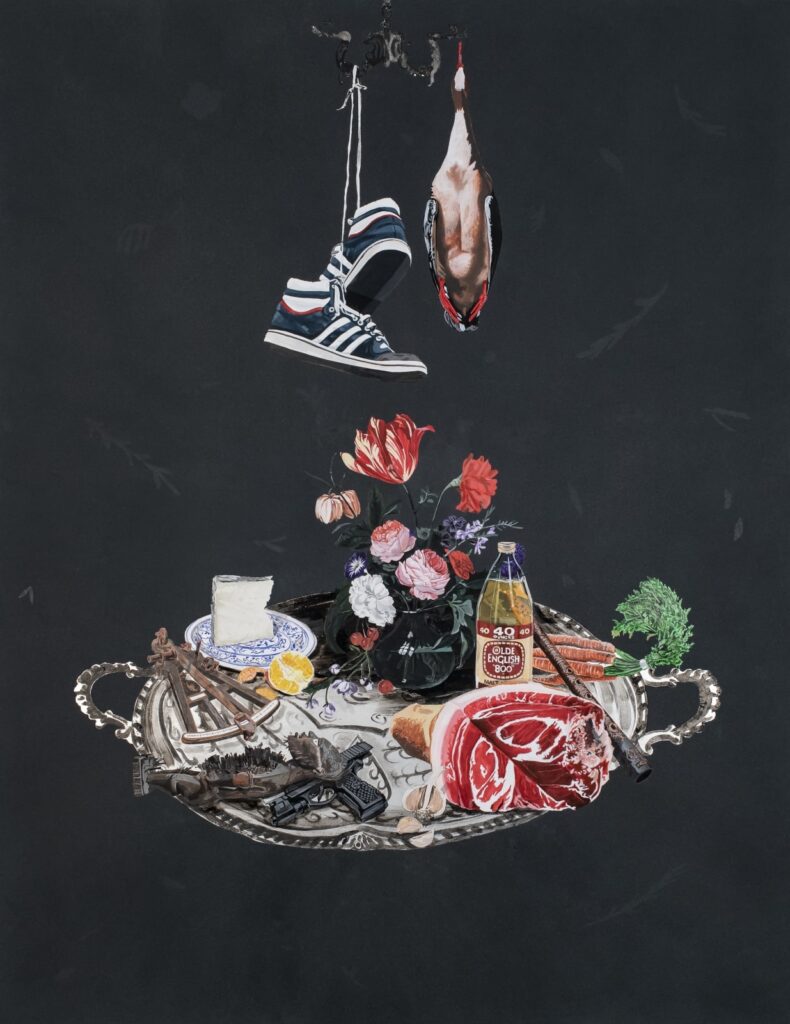

In bridging art history and contemporary culture, Villalongo’s Feast with Nkisi (2021) makes strong references to 17th century vanitas painting. Historically, vanitases use fine silverware, glistening goblets of wine, and lavish tables of food to moralize about the futility of pleasure and the vanity of material excess, while cut flowers and skulls represents the unavoidability of death. Villalongo’s dazzling painting on velvet faithfully follows the vanitas form, but extends the genre to contemporary life with a gun, a liter of Olde English 8000 malt liquor, a pair of sneakers, and a Nkisi—a Kongo amulet or object for spiritual protection or communication with ancestors. Through a system of coding, Villalongo provokes questions about our values, what nourishes us, what do we pursue, and at what costs.

In the center of the gallery, Shimoyama’s For Tamir VII (2019) beautifully holds space for Tamir Rice, who at 12 years old was shot and killed by white police officer Timothy Loehmann while holding a replica toy gun at a playground. In Shimoyama’s sculpture, Rice’s horrific death is memorialized by two playground swings adorned with bright teal, royal blue, indigo, burgundy, crimson, and purple silk flowers. Amid the cacophony of color, shimmering glass balls fill the two belt swings, causing them to slightly bow and suggesting the weight of an unseen bodies. While the silk flowers possess a levity and delicateness, they also allude to funerary flowers; the haunting stillness of the swings evokes the lack of life: They should be animated with playing children.

Through lavish color, imagery, and materials, Villalongo and Shimoyama employ coded forms to address loss and healing. The splendor and visual enticement of their work encourages an act of deep looking, in which the artists have very intentionally selected what to make visible, how to represent it, and what to exclude. Considering that Long has framed Elegies as still lives, she creates a curatorial prompt that resists direct portraiture, and engages in a dialogue of symbolism and absence. With many of the artists finding inventive ways to invoke the body and self, the exhibition extends representation beyond figuration, which is fraught with questions about how Black bodies are represented and circulated within the African diaspora, the museum context, and in the wider culture. Moreover, subtly the exhibition positions absence as a form of grace, resistance, recuperation, and reflection for the self and communities of color.