When the pandemic hit in March 2020, comedian and performance artist Kristina Wong’s tour was cancelled. She had some time, a Hello Kitty sewing machine and some fabric, so she started making masks, offering to send them to anyone who couldn’t afford to buy them.

Wong got so many requests that she asked for help on Facebook, and ended up leading a group of mostly women all around the country in a mutual aid society, the Auntie Sewing Squad. They sewed scores of masks and got them to the most vulnerable and neglected —asylum seekers, farmworkers, Indigenous communities, people on parole, and Black Lives Matter demonstrators.

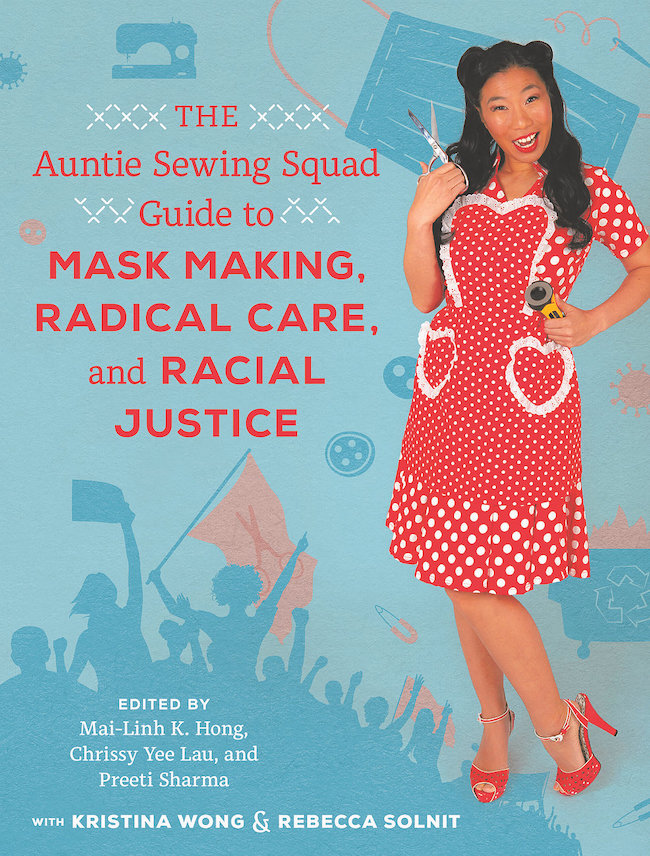

Writer Rebecca Solnit was one of the Aunties, and through her introduction to an editor at UC Press and three professor-Aunties—Mai-Linh K. Hong, Chrissy Yee Lau, and Preeti Sharma acting as co-editors—they collectively created The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice. More than 50 of the Aunties contributed essays, sewing tips, recipes (for vegan kimchi and chocolate shortbread hearts, for example), photos, and cartoons about solidarity, care, and political action during a public health crisis.

Wong, who also did a solo off-Broadway show about the experience, Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord, talked to 48 Hills about wanting history to remember that hundreds of mainly women of color stepped up to do this work, and getting requests for help from government workers, and how they’re not a cult, but they kind of are.

48 HILLS What made you decide to start sewing masks as a reaction to the pandemic?

KRISTINA WONG Sewing is something I do for my shows, and it’s always felt like this extra cute thing, like making gifts that are cute to have, but not to keep you alive. It felt empowering as someone whose never been in the position where someone runs up to me and says, “Oh, God, if I don’t have some smart social commentary, I’m going to die right now.” That never happens. I had actual people who were saving other people’s lives like firefighters and nurses who were running out of masks. I don’t know how people were able to just walk away from that, or say, ‘Sorry I need self-care, or sorry, I’ve got to watch Tiger King.’

It just sort of happened. I didn’t realize it was going to blow up. I naively offered and two requests turned into four turned into 100 turned into later 350,000 masks that were sent all over the country, right? It just snowballed. I really thought if we pushed through this together. You know, in March it was not political to wear a mask. It just felt like common sense. I actually thought this was the most patriotic thing I’d ever done. I thought whether you vote for what I vote for, you not getting sick means a lot less people getting sick.

48H When you asked for help, what kind of reaction did you get at first?

KW I made an informal Facebook group and added people I knew were sewing onto it. I thought it would be for three weeks. I realized really quickly, like two days in, we’re not experts at sewing. A lot of people who joined needed guidance and materials, which we did not have. It was just mass confusion, so I ended up in this position of telling people how to get materials. So it shifted from me sewing to me pointing people to patterns to me becoming a whole distribution system.

Fabric and elastic were coming in and out of my house 12 times a day. I felt like everything needs to be in production all the time. I describe in the show buying 40 spools of elastic for about $1,000 cash, and once it showed up it was like, get it out, get it out, get it out (snapping). It’s not protecting anybody if it’s in separate pieces in a house. As an artist, I’m in production a lot, but in manufacturing, there’s no bow. As soon as it’s out, you’re making more stuff, and that was what was hard to get used to—it’s not stopping.

48H At what point did it sort of become what it is—solidarity and political action?

KW Someone posted that farmworkers needed masks, but we were spending all day making 10 masks, so the idea of just sending off some masks and not knowing if they got there or not seemed scary. That’s when we started to do our system of super Aunties, maybe three weeks in. Their job was to call and research because you can’t just mail a box of stuff to someone in the Navajo Nation and hope it will be evenly distributed. We had to figure out the systems to get masks to day laborers and farmworkers and these really rural communities. We had to research what addresses to send stuff to. Sometimes it’s one lone exhausted organizer who can’t get to that post office.

We had to do all these calls and vetting to figure what the needs are and pin it down to exact numbers. People would say as many as you can, but for some people that means 10 masks and for some it’s 25,000. So we needed to kind of track our progress, and feel a sort of sense of completion, not just try to empty out the ocean with a teacup. A lot of it was informed by me as someone who writes grants and has to do goal setting and markers, so you can feel a sense of completion and move on as opposed to people feeling like they’re indefinitely sewing, which can feel pointless and existential.

We decided to lay out some conditions, so people could stop for a second and name their needs instead of just passing their panic onto us, because there was a lot of panic. So, you have to say I need 15 masks for this office, I will collect them, I’d like them by next week. You have to sort of set up a structure or everyone will feel helpless, and it’s just like people going, “Homeless people need masks!” Yelling at me is not going to help. We needed some tangible steps.

48H How did Rebecca Solnit get involved?

KW: Rebecca is a friend of Auntie Valerie Soe, and Rebecca has written about mutual aid groups that come around in crisis, so she got involved. We call her the historian-writer-shakedown Auntie. She wrote about us in the Guardian, and she’s sort of the hype lady with this fanatic following. She would put the bucket out for us. Fundraising was the least difficult thing about this group. It was labor, materials, and organizing all these Aunties we’d never met before and dealing with our own exhaustion. The last thing was the money, thankfully.

48H When did you decide to do the book?

KW We have a bunch of academic Aunties who were like, “Wow, this is so deep how this fits into our histories of immigration and histories of sewing.” There was a very strong Asian American female contingent in this group and some of the academics wanted to talk about it. One of the Aunties, Grace Yoo, turned it into a summer class [at San Francisco State] that was a combination of sociology and having students sew. And while they were sewing and learning to sew, speakers who were organizing different campaigns would come talk.

It felt like a strange public health class. We were learning about all these communities and systems and how do we get them have the resources they need to work better. And Rebecca introduced us to the publisher at UC Press, and then it happened very fast. I’ve pitched so many books in my life, and this one went to press so quickly.

“Uh, I know you are used to pressing two buttons and something shows up the next day, but that’s not how this is going to work.”

—Kristina Wong

48H What was it like performing the related show Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord during the pandemic?

KW People were like, “Kristina, just write a show about this,” and I was like, “That sounds terrible. Who wants to relive this shit?” But running this group I had such a strange POV of this situation. And I was witnessing all these women and Asian Americans doing this work, so I was like, I want history to remember that we stepped up to do this. It felt like the labor of sewing is historically so invisible and undervalued.

This was sometimes reflected back to us in people saying something like, “Can you just sew up something like this for me?” It was like, “Uh, I know you are used to pressing two buttons and something shows up the next day, but that’s not how this is going to work.” A lot of it was I wanted to educate people and remind them that we did this work, and we weren’t just people who quietly clutched our pearls watching our family members be beat up in the street. We also are people who did solidarity work, and who really fucking cared and stepped up. For me that was a lot of impetus to make the show.

48H One review of the show mentioned how you balanced a feel-good story with an indictment of American society. Could you talk about that?

KW I think you associate people who sew with oh, She just loves to sew. I used to enjoy sewing, but not when I’m doing it eight hours and worrying someone is going to die and all these nurses are in my inbox screaming that they’re going to die. That’s not fun.

We had these inside jokes that we were a sweatshop and some of Aunties weren’t happy about that word, but I think the word volunteer sounds too tame, and it sounds like we just enjoy cleaning up after the government. That’s why our humor was so in a gallows direction. It was like, this is so dumb. We should not be in this position.

It got to the point where the government was asking us for help because we were faster. I got an email from a social worker in Alameda Country with gov in her email, she had this long ass list of stuff she needed for this backpack drive, and I pushed back on her because she gets a salary and I am in my underwear right now, and she said, we’re dealing with so much red tape, we’re asking the sheriff’s office help her get this stuff, and I was like, fine, fine. Who seems to fucking care? It’s the Aunties.

48H How did you end up calling yourself the Sweatshop Overload?

KW: It just sort of happened. We were trying to figure out better titles than captain or leader. So I leaned into the persona more I would threaten the Aunties like there’s this persona of the cruel sweatshop overload who threatens to cut your fingers off. It just became this form of entertainment. Especially once kids started to help. This is getting so ridiculous—we’ve recreated the sweatshop in America. It was a tongue in cheek thing that sort of stuck.

I was calling the show in progress Sweatshop I feel like a cult leader sometimes, and we’d make jokes like, “We’re not a cult. We’re totally a cult!” It felt like we had built this weird utopic homesteading community during doomsday. And we have this weird language with each other where everyone is Auntie so-and-so. It felt bonkers by the end.

For a lot of these Aunties they have felt love in a way they never have before which also feels crazy and cultish to say. But I feel like all these people are my family members and I’m connected to them just because of this unconditional willingness to give.