Michal Barba, who is a good reporter, broke the story first in the SFStandard: Recology may have overbilled San Franciscans for even more than the $95 million the company has had to pay back as part of the ongoing City Hall scandal.

Other news outlets have picked up the story, but nobody has explained exactly what went on here, and how Recology could be on the hook for a lot more money.

There are two major factors at play here, and both of them show the problem with a single company operating as a City Charter-sanctioned monopoly with a perpetual no-bid contract—and of late, at the Department of Public Works, little to no oversight.

The way the current system works—and Sup. Aaron Peskin is trying to change that—Recology never has to submit a competitive bid. Instead, like PG&E, another government-sanctioned monopoly that has more than its share of problems—the city is supposed to closely regulate its rates.

So every few years, Recology submits an application for a rate hike. That goes to a city oversight team that analyzes it, and in the end, the head of the PUC (for years, Mohammed Nuru) makes a final decision.

As part of that application, Reclogy (like PG&E) has to submit a bunch of financial statements that demonstrate how much money the company needs. It’s more of a budget than a bid; Recology explains its costs and gets a reasonable profit level (you can see the figures here) and the city approves the deal.

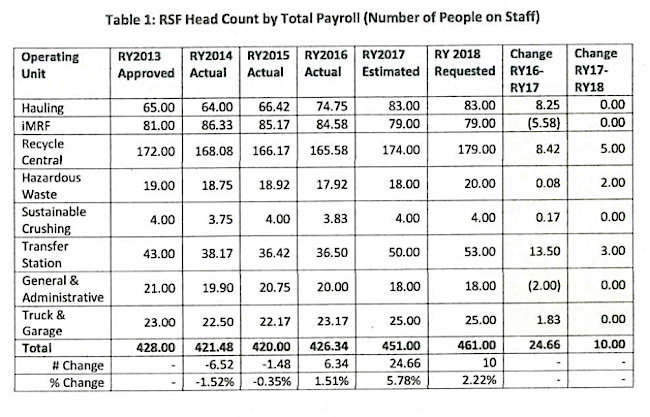

So if you take a look at Exhibit 23 from the 2017 (most recent) rate case, you can see an interesting trend. Recology in 2013 had approval to hire 428 people, but the next year, the payroll was only 421. The next year it was 420.

This happens in the city all the time; a department has approval to operate with, say, a staff of 50, but people retire or quit, and it takes a few months to find and process a replacement, so at the end of the year there’s an “attrition dividend,” money that wasn’t actually spent on authorized hiring, and that money goes back into the General Fund.

At Recology, it apparently just goes back into Recology profits.

For 2018, the company requested 461 people. I don’t know, because the company has so far declined to answer my question, how many workers there really are on payroll, but I bet it’s fewer than 461.

That’s one of the things the city Controller’s Office is looking into. Peskin told me he doesn’t have any more hard data, “but when the controller of San Francisco says he has concerns and is investigating, those are big words.”

I have contacted Recology’s media office repeatedly, but they have not responded.

Then there’s this piece of property that Recology sold to Amazon. It’s at the foot of Potrero Hill, and the company doesn’t need it any more. It’s a big piece of land, and at one point Recology wanted to develop it for housing. Instead, Amazon bought it for $200 million and plans to turn it into a new distribution center.

Recology has owned it since 1971. Right before the sale, Assessor’s Office records show, it was assessed at about $3 million; under Prop 13, that means Recology paid a bit less than that, probably about $2 million, for it 50 years ago.

So there’s a good bit of profit here—like, almost $200 million.

Who gets that money?

Well, if the ratepayers paid for the property in 1971—that is, if the 1971 rate case included the money to pay for it—then one could certainly argue that the ratepayers deserve some of the profit.

Of course, in 1971 Recology didn’t exist; Sunset Scavenger and Golden Gate Scavenger were later combined into the holding company. It’s going to take some work to sort this all out.

But that’s one of the things the Controller’s Office is investigating.

So there’s a lot here, potentially very big money.