For every reader yearning heart and soul for rationality, solace, humor and, let’s say it, anything resembling grace, after the last few years, disappearing into a book can be the best medicine, surpassing even mind-enhancing, mood-altering drugs or alcohol. Books can be better than talking to a therapist or your mother, your dog or the nearest houseplant when it comes to providing all-too rare low-cost or free comfort.

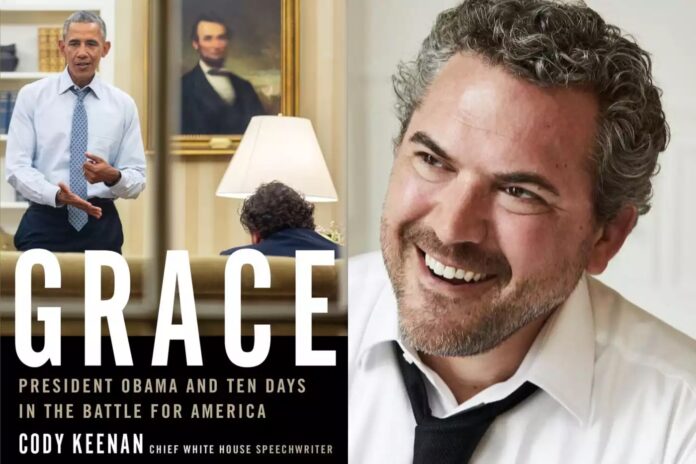

Grace: President Obama and Ten Days in the Battle for America, penned with impressive flair by Obama’s longtime collaborator and chief speechwriter, Cody Keenan, is for some, a much-needed literary remedy.

Published in October, just prior to the 2022 mid-term elections, Keenan’s book is a political memoir told through the aperture of a 10-day period during Obama’s presidency. The story begins on June 17, 2015, the day a white supremacist murdered nine Black worshippers in a church in Charleston, South Carolina. Blending gripping scenes, often surprisingly humorous personal anecdotes, and throughout written with reverential tones when describing his boss and the former president’s ethics, writing skill, and actions, Grace is a tale that is—to paraphrase a well-known African American spiritual—like the balm in Gilead that, with its sweet sound, makes the wounded whole and heals sin-sick souls.

Admittedly, Keenan is one-hundred percent a fan of Obama and for people who believe “DP” preceding a name means Demonic Person and not member of the Democratic Party, the book will read differently… if it is read at all. History clearly tells us that beauty is in the eye of only some beholders when it comes to our country’s first Black president.

But for those who do choose to read, we learn that at the same time the horrific hate crime occurred in Charleston, the Obama administration was also facing enormously important Supreme Court decisions concerning health care and marriage equality. While fielding all the usual pressures and responsibilities of their roles as United States chief executive and the POTUS speech writer, respectively, Obama and Keenan constructed numerous speeches, among them the annual State of the Union address and the high-stakes eulogy Obama planned to deliver at the funeral for the Charleston Nine.

Regarding the latter, Keenan combines their all-night writing sessions, a remarkable decision by the families to offer forgiveness to the mass shooter, and a series of serious setbacks, reversals, internal reckonings, and personal challenges related to and unrelated to the tragedy in Charleston to create the book’s centerpiece: a story that is gripping, nail-biting, and steeped in the best and worst of humanity.

Along the way, facts jump out: over 300 mass shootings occurred in 2015 alone; the shooter in Charleston, Dylann Roof, fired 77 bullets with 66 hitting church worshippers; Felicia Saunders, the mother of 26-year-old Tywanza Sanders who was killed, used the word “mercy” in statements addressed to her son’s murderer, causing Keenan to write, “It was moral whiplash, from massacre to mercy in a matter of minutes.”

That level of grace amid the awful indignity and injustice is nothing short of amazing and necessary. Especially today, when politicians and media and honestly, public expression comes from people chattering loud, louder, loudest—and rarely in tones and words recognizable as learned or lovely or level-headed. It is as if everything that enters the human brain must be shared at peak volume—without restraint and the more famous or rich the speaker and more outrageous the declarations, the better.

Blessedly, what is amplified in Keenan’s chronicle are the voices of two men (Obama and Keenan) wrestling with their private and public identities and resisting, while knowing they are part of, the political machinery that pumps, roils, lurches, and lurks behind every national decision. Even so, they search for words to counter the racism and violence rippling through America’s society and culture. They aspire to uplifting hopefulness — to grace — in an era of cynicism, suspicion and conspiracy theories.

Keenan paces the story well, managing a slow tempo without “teasing” or false suspense. During the tumultuous minutes, hours and ten days that led up to Obama in an all-expectation-defying moment singing at the funeral in Charleston another great spiritual, Amazing Grace, we see the pinnacle moment rising. Ultimately, Obama declares he will speak in his eulogy of how the families “ushered in the opposite of what the killer intended,” and says, “…that’s what I want to talk about. The concept of grace.”

We also receive along the way James Baldwin’s marvelous, “There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.” We are reminded that as a country, we had already crossed Baldwin’s threshold after failing to pass stricter gun legislation following the Newtown school shootings in 2012. How many times would the power of the gun lobbying NRA and the stranglehold of assault weapons leave families and entire communities decimated?

Another time, discussing the upcoming State of the Union address over a lunch of baby carrots and baked chicken, Obama mentions trumpeter Miles Davis and what made him great. “It’s the notes you don’t play. It’s the silences. That’s what made him so good. I need a speech with some pauses, and some quiet moments, because they say something too. You feel me?”

Keenan, whose tendency as a wordsmith is to over-write, manages to channel a favorite phrase of Obama’s daughter, Sasha, “you do you, man.” This scene echoes one later in the book, when Keenan writes of the eulogy speech and the 11, elegant, silent seconds before Obama sang the spiritual song’s first glorious words, “Amazing Grace.”

Keenan writes that in that moment he saw and heard liberation. I say read this book and find for yourself liberation—and possibly, consider the reward, restitution, resolve and restoration that rise from delivering or receiving desperately needed grace. Surely we can agree that none of us lives well without it.