Watching Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God for the first time as a teenager, Thomas von Steinaecker was shaken. Never having seen anything like it before, he was convinced that his television set was on the fritz.

The trailblazing 1972 film—the German auteur’s first of five collaborations with notoriously temperamental actor Klaus Kinski—tells the story of a mad Spanish soldier steering a motley crew of conquistadores on a treacherous quest through the unforgiving Amazonian jungle for the mythical city of El Dorado. A sociological study of the perils of greed, forced indoctrination, and racial superiority, it achieved an arthouse release in the US in 1977 and would go on to influence Francis Ford Coppola’s consequential 1979 film Apocalypse Now.

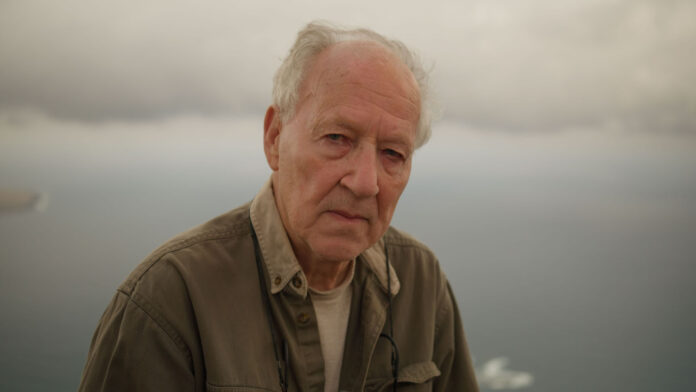

“It was a shock,” says the documentary filmmaker, whose movie Werner Herzog: Radical Dreamer, which explores the fascinating life and career of the idiosyncratic pioneer of New German Cinema, comes to the Berlin & Beyond Film Festival on Sat/25. “I had never seen anything like that before.”

From 1982’s Fitzcarraldo (about a Peruvian rubber baron dead set on transporting a steamship over a steep hill to access a rich rubber territory in the Amazon Basin) to 2005’s Grizzly Man (focusing on a real-life bear enthusiast who fell victim to one of the carnivorous creatures he so admired)—Herzog’s films feature ambitious protagonists with impossible dreams, often in conflict with the world around them.

Von Steinaecker discovered that Herzog himself was such a character after reading Herzog’s 1978 diary Of Walking in Ice, about his perilous trip on foot from Munich to Paris in the fall of 1974 to save the life of his friend and fan, film historian Lotte H. Eisner.

No stranger to pulling stunts, Herzog made the papers after famously cooking and eating one of his shoes in an attempt to spur fellow film director Errol Morris to complete a documentary he was procrastinating on.

“Herzog was unlike anything else I’d seen so far,” says Von Steinaecker. “At the same time, all his works seemed to have a mystery that was hard to grasp.”

His documentary compiles interviews with the idiosyncratic moviemaker and Herzog’s many acolytes, including Nicole Kidman, Christian Bale, Robert Pattinson, Wim Wenders, Joshua Oppenheimer, and Chloé Zhao. Their words are paired with never-before-seen archive footage and memorable film excerpts, painting a compelling portrait of the visionary artist whose life proves stranger than fiction.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

I spoke to Von Steinaecker about collaborating with Herzog on Radical Dreamer, how his perceptions of Herzog changed over the course of making the film, and the movie that every fan of the idiosyncratic filmmaker must see.

48 HILLS How did this project get going?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER It had always been my wish to explore the mystery of Herzog’s works, find out more about the person who created all this, and who was accompanied by rumors—and most of all, the reputation of being inaccessible, which is of course, the biggest motivation for a filmmaker to meet this person anyway.

So one day I contacted Werner’s film company, which consists of his brother Lucki. Lucki immediately called back and we instantly had a rapport. Since it was COVID time, I could not visit Werner in LA, so to introduce myself, I sent him two of my novels, which impressed him.

During [Herzog’s and my] video call a couple of weeks later, we mostly talked about literature, especially the insane German poet Hölderlin. After two hours or so, Werner said, “OK, let’s do this together.”

48 HILLS How did you decide who to interview? Why were all these legends so eager to chat about Herzog?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER For me, it was important to meet his most important collaborators, including Thomas Mauch (his director of photography), Lucki (the unsung hero in this story), and his first wife, Martje, who was there right from the beginning. There are so many stories told by Werner that sound rather like legends than real events. So one of my goals in asking these collaborators was to find out what really happened. And strangely enough, most of these “legends” turned out to be true.

On the other side, it was important to me to cover Werner’s career in the US, which is mostly ignored in Germany (Grizzly Man, for example, only saw its release on DVD.) It also sounds almost like a fairy tale that Werner has become such an icon there. Why are people so fascinated by him there? So it was clear that I wanted to hear more about this from the actors he worked with in the US. And I think it says a lot about him that they all were instantly willing to give interviews.

48 HILLS Herzog says in the film that most people don’t know how to deal with him. How were you able to?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER I think you either have a rapport with Werner at once—or never. He listens very much to his gut instinct when it comes to trusting people. I was lucky that he liked me the minute we met.

Of course, you have to be prepared when you talk to him. You should know about his films, and not only the ones he directed in Germany. And I knew that writing for him was as important as making films. When he feels that there is a genuine interest in him and his works, he really opens up.

48 HILLS What do you think makes him fascinating?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER He took risks to realize his films that hardly anybody would have been prepared to take. Also, he often went for the unexpected. As he said, he does not have a career—things just happen to him. Of course, Werner knows very well how the film business works, and he likes to provoke. But nobody would talk about him if there was not a very substantial core.

The most remarkable thing for me about him is not so much working together with the impossible Klaus Kinski and pulling a ship over a mountain, but having moved to Los Angeles without knowing what was going to happen. He had no ties to Hollywood and never became part of the business there.

48 HILLS Have your perceptions of him changed since making the film?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER Werner was sort of a mystery man when I started the film, a mystery not so much created by himself but by others. Getting to know him, I realized how disciplined he is. I expected a romantic artist figure. But his motto is, “Do the doable,” which is very fitting for him. He’s far more pragmatic than one might think. And he likes FC Bayern München a lot. I did not expect that.

48 HILLS What’s his importance to German cinema?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER Together with Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Wim Wenders, he was at the center of what is called today the “New German Cinema.” These three (together with a bunch of others) revolutionized German post-war cinema. Werner stands out in that he was never interested in German everyday life like his colleagues, but in jungles. Werner seems in a league of his own, living in “Werner world,” as Nicole Kidman put it in the film. This may explain why a film like Aguirre, now over half a century old, has not aged at all.

48 HILLS Which of his films is your favorite? If someone could only see one Herzog movie, which should it be?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER I like The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser best. The cinematography is achingly beautiful, almost like paintings. The script is touching and thought-provoking at the same time. And Bruno S., the street musician Werner found in Berlin, is unique in his performance. Some people might find the Kinski films more impressive and they are, of course, all outstanding. But Kaspar Hauser would be my first choice.

When it comes to his documentaries, I opt for Into the Abyss, the true crime story to end all true crime stories. Who would start such a story with a meditation on squirrels?

48 HILLS Why is his work, as he says in the movie, less appreciated in Germany?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER The main reason is that he does not live in Germany anymore and that his films do not deal with German life. They never did. Also, his very special sense of humor is not appreciated in Germany. He can be very self-ironic, something that is more American than German, I think. To be precise, he’s not German, but Bavarian, and therefore has a style of thinking and living that someone outside of Bavaria cannot fully understand.

48 HILLS He speaks in the film about his immense productivity during COVID. What do you think keeps him going at age 80?

THOMAS VON STEINAECKER Werner is a real artist. That means he just has to be productive. Everything he does he turns into a piece of art. It’s impossible for him to retire.

BERLIN & BEYOND FILM PRESENTS WARNER HERZOG: RADICAL DREAMER Sat/25 1pm, $13-16. Roxie Theater, SF. For tickets and more info go here.