Amalia Mesa-Bains may be a feminist and additionally a pioneering Chicana artist known for agitating for a more equitable art world—but certainly has time to enjoy sparkle and joy. In an interview with 48hills, she fondly remembered going to big quinceañeras and Mexican Independence Day parties, as well as her mother and father getting dressed in elegant outfits to go dancing.

She wanted that same beauty and abundance to be evident in her work—even at the risk of bad reviews, such as that of one critic who called her a folklorist with “too much glitter.”

But Mesa-Bains didn’t see anything wrong with glitter.

“I took to the metallic, the reflective, and the mirrors and all of that because I wanted to destabilize the viewer and engage them in the work and make them feel like they were part of it, and for them to experience the beauty of that particular moment,” she said at a preview for her show at the Berkeley Art Museum, “Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory” (which runs through July 23.) “Beauty, power, and resistance can all be hand in hand. They’re not separate.”

Mesa-Bains has won many awards, including the MacArthur Genius grant, and she has had her work shown in institutions such as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and the Smithsonian, but this show at BAMPFA is the first retrospective of her work, comprised of more than 50 pieces. These works include the altars and ofrendas for which she’s known, like “An Ofrenda for Dolores Rio.” And for the first time, all four autobiographical installations of her “Venus Envy” series chronicling her life as a Chicana woman over the course of several decades are being shown together.

This work is couched in deep academic experience. Along with her BA in art from San Jose State University, the Santa Clara-born Mesa-Bains has an MA in interdisciplinary education from San Francisco State University and a PhD in clinical psychology from the Wright Institute in Berkeley. She taught and developed curriculum for the San Francisco Unified School District, and co-wrote a teachers’ guide called Diversity in the Classroom. She also worked as a research associate at Far West Laboratory.

So understandably the show’s curators, Laura E. Pérez and María Esther Fernández, seemed beside themselves when talking about Mesa-Bain and her work at the preview.

“Amalia has labored not only to uncover the hidden histories of women, immigrants, the undocumented Mexican Americans, Chicanx, and communities of color, but to counter the psychologically and spiritually dehumanizing effects of patriarchal Eurocentric classism and racism,” Pérez said.

The show begins with “Venus Envy Chapter I: First Holy Communion, Moments Before the End,” which, along with addressing Mesa- Bain’s communion, also centers on her relationship with her family, Fernández said, adding that as a curator she was interested in personal stories.

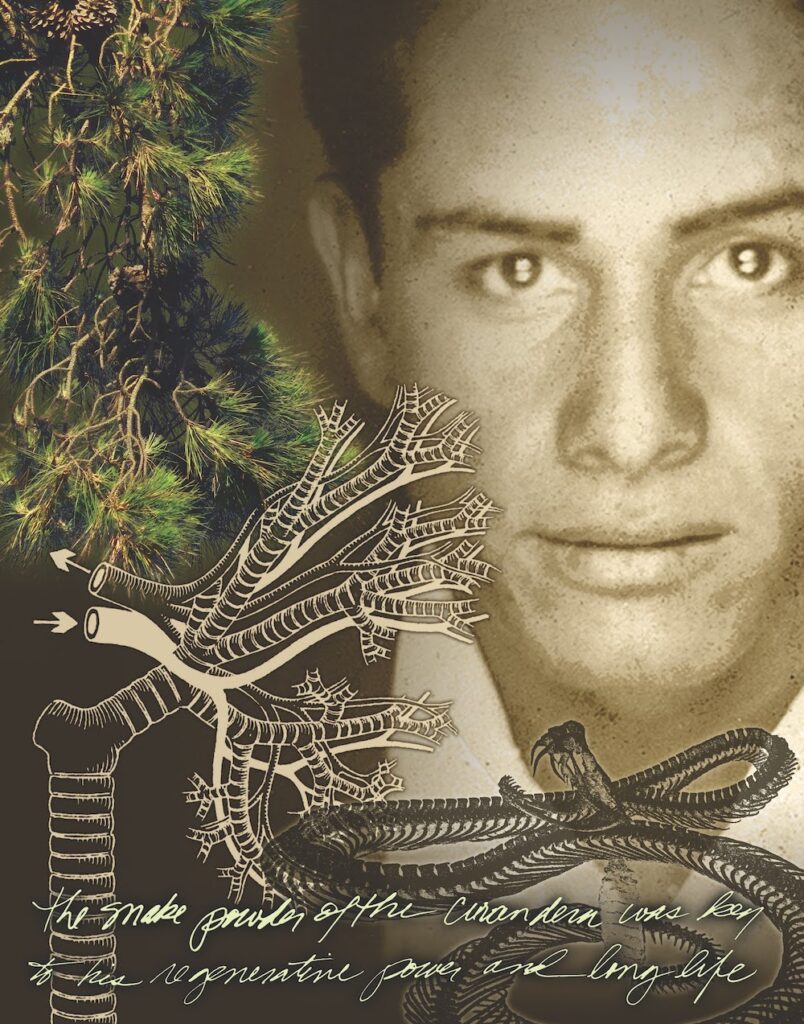

Chapter II in the series is “The Harem and Other Enclosures,” Chapter III is “Cihuatlampa, the Place of the Giant Women,” and Chapter IV is “The Road to Paris and Its Aftermath, The Curandera’s Botanica.”

Mesa Bains talked about how this last installation, which includes a large medicine cabinet, deals with a car accident 20 years ago that nearly killed her. She had to work hard, not to just recover physically but to overcome her anxiety and depression.

“I realize it was a story I needed to tell because it was in a long history of her family’s healing,” she said. “The medicine cabinet has a shelf for every member of my family — their illnesses, their healing their joys, their fears, and in the time since I completed this, they are all gone now, so the cabinet is very precious to me because my mother, father, sister, and brother are not with me anymore.”

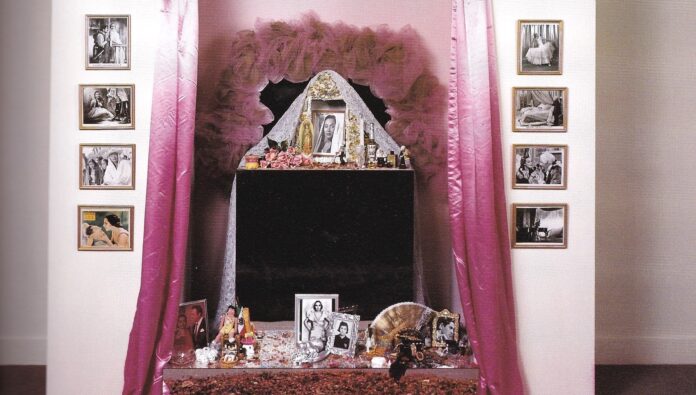

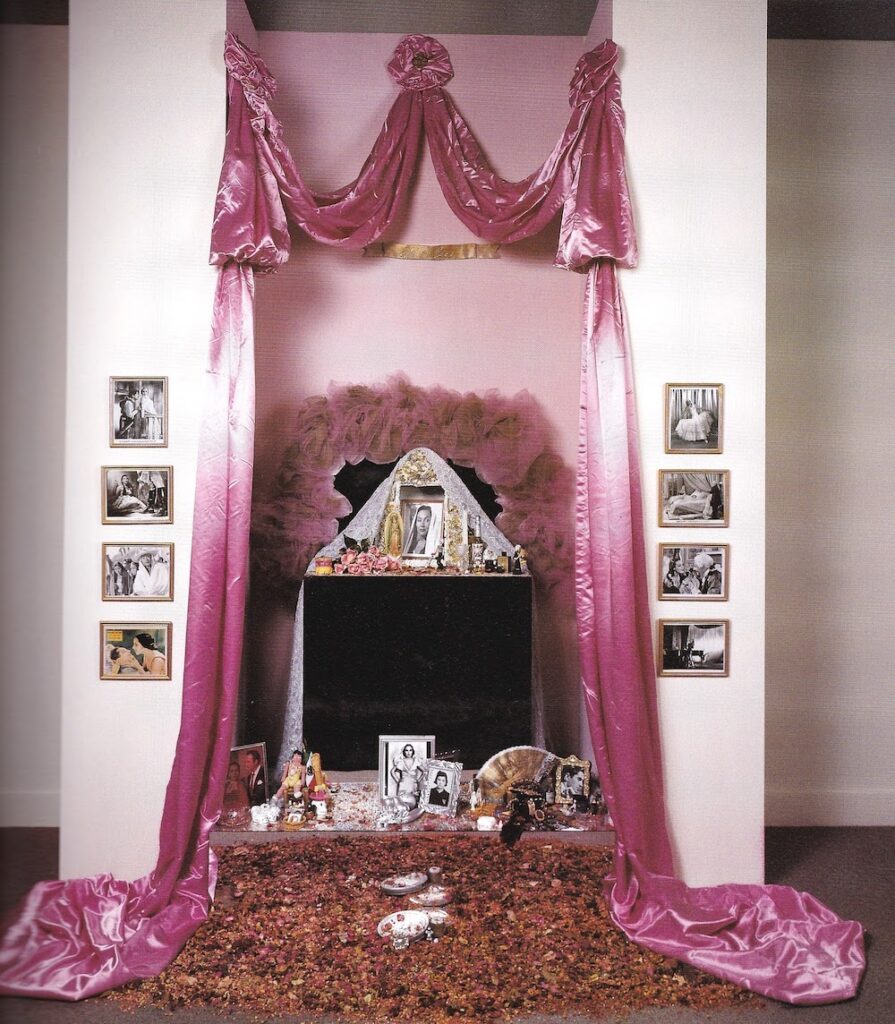

The final piece in the show, “An Ofrenda for Dolores del Río,” is covered with Hollywood photos of del Rio that nestle into and around theatric, gathered pink satin curtains. The curators talked about how with her altars, Mesa-Bains had taken something with a religious function to explore what is sacred.

“The altar is a vehicle of really thinking about the social, historical, the political,” Fernández said. “And the deeply personal as well.”

Del Río was a Mexican actress with a 50-year career. In the pre-civil rights era, she had to do a lot of negotiating in Hollywood not to be stuck with the role of the barmaid, the whore, or the servant, Pérez said.

“For Latinx actors and for women, we’re still just breaking out of the stereotypic roles that are highly racialized,” she said. “So, this is also a great example of personal icons and personal models for beauty. That’s Brown beauty up there.”

There are dried flowers on the floor in front of the piece, which Mesa-Bains employs in much of her work. Museum officials told her she needed to have a boundary so that people couldn’t touch her art, and in what she calls “floor work,” she uses broken glass and potpourri, including rose petals, lavender, and pine. But the flowers are much more than a boundary, she says.

“I began to realize it also had this other element, which is the seduction of scent, of aroma,” Mesa-Bains said. “Scent gives memory. Much of my work is concerned with the idea of memory—not for the nostalgia of it, but because it takes you back to a time and makes you ask questions about what happened.”

AMALIA MESA-BAINS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEMORY runs through July 23. Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. More information here.