Seldom does synchronicity prevail so fortuitously as it did recently, on a blustery, high wind day in February when a gigantic eucalyptus tree on Treasure Island catapulted into afternoon traffic on the always-congested Bay Bridge. The mess and disruption closed westbound lanes for hours, and caused the usual gawk-at-calamity behavior from drivers headed east, jamming up both directions.

Certainly, it would have meant the equivalent of at least a quasi disaster if a tree and ill wind had combined to prevent a visit to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor to see “Sargent and Spain,” the first exhibition exploring the influence of Spanish culture on artist John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). The mention of serendipity and falling trees—thankfully, no one was injured in the bridge incident—in the context of the Legion’s art show (which runs through May 14) is a roundabout way of saying this is a splendid exhibit not to miss, even if to see it, one must drive around or even climb over a fallen tree.

Drawing upon artwork based on seven visits Sargent made to Spain between 1879 and 1912, the exhibition’s oils, watercolor, drawings, photographs and additional materials chronicle an era and create a magnificent, eclectic cultural “map” of Madrid, Granada, Tarragona, and other Spanish locations. A secondary narrative of the exhibit illustrates the development of an artist in the late-19th and early-20th centuries.

Born to American parents in Florence, Italy, Sargent never lived in the United States, but nonetheless influenced generations of American artists. When he first traveled to Spain from his homes in London and Paris, he was a 23-year-old man just starting his career and was dazzled by the country and people he encountered. His seventh visit came 32 years later as a mature artist who had by then intently studied the paintings of other artists, and worked voluminously. Sargent’s evolutionary arc from early genius to a master painter is visible and intriguing.

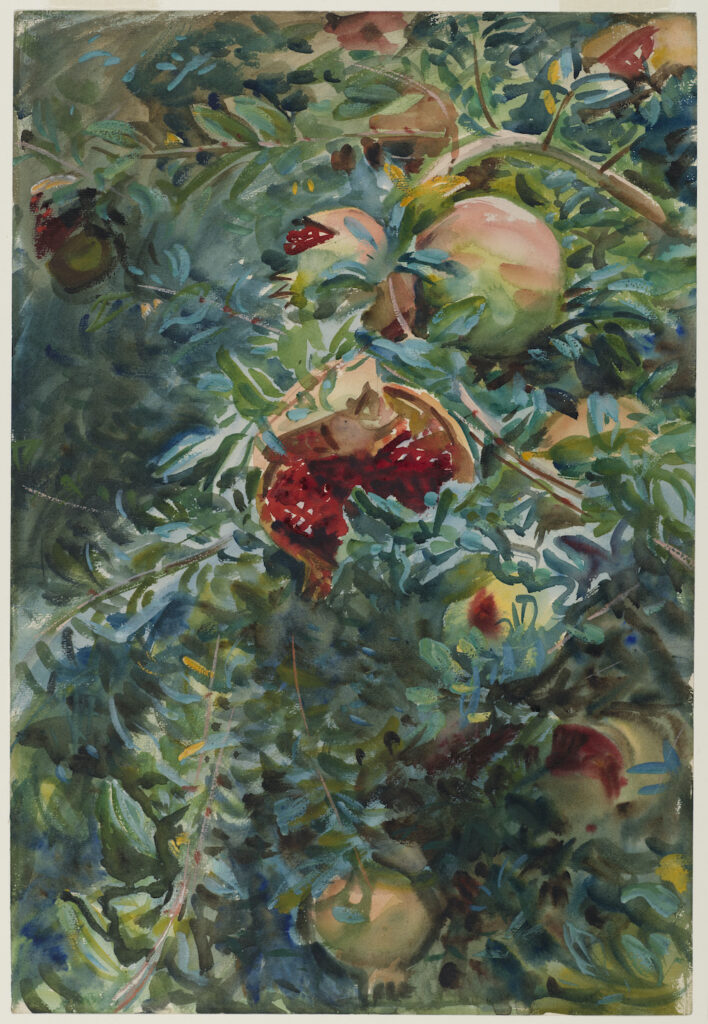

Most fascinating about this astutely curated show (more about that to follow) is that Sargent; who was recognized widely by scholars, art experts, collectors and admirers as a “definitive society portraitist;” is revealed as a true artist’s artist. Visitors to “Sargent and Spain” behold countless studies of a Spanish dancer’s outstretched arm, and multiple drawings of a man’s profile as seen from the upward-gaze perspective of what could be a fly on his chest. In reference photographs, quick paint studies, or culled batches of charcoal sketches of fig branches, pomegranates, frescoes, porches, church vestibules, palace courtyards, pubic fountains, and more, there is proof of the tremendous work behind Sargent’s talent.

The energy of his studious, exhaustive approach is so palpable a viewer can almost hear it rumbling and roaring like an obsessive, unstoppable engine behind every finished painting.

“Sargent in Spain” is curated by Sarah Cash, associate curator of American and British paintings at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; along with Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond, leading authorities on Sargent. The Legion’s presentation is organized by Emma Acker, associate curator of American art at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Acker has done a marvelous service to everyone, from the Sargent novice to authorities on his work. There is not a single misstep in the well-designed display that encourages individual pacing—be it casual meandering, a rapid lunch-hour blitz, or an hours-long “residency” that allows time to scrutinize every detail and revisit favorites before departing.

Much like the tree that could have meant a messed-up trip, but didn’t, it is synchronicity of subject, timing, purpose, and design that allows everyone access with ease. There is artistry in the size, pacing, and placement of information panels; the particular selection of artworks combined in one room; and the show’s overall, sequential flow that ultimately tells an unforced story of a man’s love affair with Spain and the Spanish people.

The exhibition presents Sargent’s work in six sections: “Velázquez and the Spanish Masters;” “Dance and Music;” “Architecture and Gardens;” “The Land and Its People;” “Majorca;” and “Spirituality and Religion.” There are too many highlights to name them all, but these few offer a good start.

“Velázquez and the Spanish Masters” includes paintings by Spanish Old Masters—Diego Velázquez in particular—whose work fascinated Sargent. While at the Museo del Prado in Madrid, he created studies and paintings that demonstrate in their color palette and brushwork the influence of his favorite mentors. Comparing and contrasting their works and his paintings from this time holds interest in itself, but also serves as introduction to Sargent’s eye. We see what the artist saw; especially in a study after the style of Juan Bautista Martinez del Mazo that is entitled “The Infanta Margarita,” and more poignantly and powerfully in his brilliant, timeless portrait, “A Spanish Woman.”

Music was a significant element in Sargent’s life; his mother was a skilled pianist, as was the artist himself. Visual art and music were therefore entwined threads that led to his interest in Spanish dance and a clear fascination with flamenco. His “El Jaleo,” created in 1882, is considered an early masterpiece. Dramatic, dark, exquisitely expressive, it exudes joy, passion, sensuality, tension, and release. It is a painting that feels completely spontaneous but is nevertheless underscored by a bevy of related charcoal drawings of hands, arms, legs, torsos, heads, and dancers or musicians in a variety of postures. Similarly, every component of the breathtaking “The Spanish Dance” from the same time period came about after Sargent used up what looks to be an entire forest’s-worth of paper with numerous drawings and several color studies.

In Majorca, two visits Sargent made to the Mediterranean island and painting plein-air (painting on location outdoors), resulted in Sargent’s “Majorcan Fisherman” (1908). The work is dizzying and dynamic. The confrontational gaze of the young fisherman cantilevered on the painting’s left edge can’t be ignored, although the blazing blue sea and the abstract distortion of a curvaceous railing and jagged shadows cast on the ground by a thatched roof spin the viewer’s eye in multiple directions.

“The Land and Its People” offers further examples of Sargent’s investigation of off-centered compositions, often deployed with thicker oil paint or quick, looser brushwork when working in watercolor. “Alhambra, Patio de los Arrayanes” (1879), an early painting of the palace complex’s famous Court of the Myrtles, is one such example of the former; “Blind Musicians” (1912), a fine watercolor over graphite painting of the latter. In both, brushwork is gestural, capturing nuance without, upon close examination, being detailed. For example, a musician’s face has no actual eyes drawn or painted. Nonetheless, we feel—are certain—he is looking straight at us.

The gallery designated as “Religion and Spirituality” houses materials related to Sargent’s interest in iconic Spanish Catholic religious imagery. Included are his numerous studies of cathedrals, crucifixions, and Madonnas (many created in preparation for the commissioned Boston Public Library mural cycle “the Triumph of Religion”) which are given firm foundation by the inclusion of photographs and small sculptures from his personal collection.

With more works begging for attention, it’s best to see for oneself what Sargent laid out wondrously with simple tools: oils, watercolors, paintbrushes, and charcoal pencils. A visitor might discover there is a third narrative in an exhibit of a portraitist’s work: “Sargent in Spain” tells of an artist in a certain place at a specific time, yet is a timeless story of being in love with craft, location, people, and subject.

SARGENT AND SPAIN runs through May 14. Legion of Honor, SF. More info and tickets here.