I just returned from a nine-day educator-exchange trip to Cuba. I traveled with a group of five faculty members and 36 graduate students from the University of Maryland and George Washington University. The program, Busquedas Investigativas, has organized opportunities to share educational research and practice between Cuban and US colleagues since 1994.

As a retired professor of education affiliated with the University of Maryland (though now living in Santa Cruz), I have participated in this program (originally called Seminario) several times over its 29-year history. This year we had lectures by Cuban and US participants, took part in seminar discussions, and visited a range of educational institutions (preschools, primary schools, lower secondary schools, upper secondary schools, and universities as well as research institutes).

Overall, I was struck by the enthusiasm of Cuban colleagues involved in the program as well as the educators, students, and researchers we met during visits. This is despite the hardships and challenges that they told us they faced—due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic but in large part due to the 60+ year US blockade, including the ratcheting up of sanctions by the Trump administration which have only minimally been reversed by the Biden administration.

Several colleagues also called specific attention to the problems Cuba faced because Trump had (re)placed Cuba on the State Department list of State Sponsors of Terrorism – an inclusion that is both erroneous and cynical, given that Cuba has been the target of terrorist actions sponsored or condoned by the U.S. government for decades (for more information, go here.

I wish there was space to share all the experiences I had, but I hope that readers will join one of the many opportunities to travel to Cuba themselves.

Let me start with some notes about Cuba’s experience with COVID compared to that of the US. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 22 February 2022), the US recorded three times the number of cases of COVID per 100,000 people than did Cuba (30,496 vs 10,200) and witnessed 4.4 times the number of COVID-related deaths per 100,000 than did Cuba (332 vs 75).

These dramatic differences can be attributed to the overall health of the Cuban population pre-COVID, the coordinated and extensive efforts by the Cuban public health system to monitor and treat—and eventually vaccinate—the population, and the Cuba people’s general respect for science and receptiveness to scientists’ recommendations (wearing masks, getting vaccinated).

We learned that Cuba—like most of the world—closed schools (but not preschools) in March of 2020. Like many countries, but more uniformly and energetically, Cuba transitioned to distance education modalities (notably television, radio, WhatsApp, and distributing printed materials). While Internet-based strategies were employed, primarily in larger cities and tertiary-level institutions, these were limited by the blockade’s restriction on access to certain platforms like Zoom.

Moreover, research conducted in a large national sample of pre-university educational institutions by the Central Institute of Pedagogical Sciences, based in Havana, found only a limited degree of lost learning compared to what was projected in to occur normal years.

I should mention that the success of Cuba’s education system was previously demonstrated in findings from the Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study conducted by UNESCO’s Latin American Laboratory for the Evaluation of the Quality of Education in 2019, a year before the pandemic.

For example, 48.3 percent of Cuban third graders scored in the higher levels (III and IV) of the mathematics test, outperforming all other 17 countries that participated in ERCE (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, México, Nicaragua, Panamá, Paraguay, Perú, Dominican Republic, and Uruguay).

Also memorable for me was a visit to a mixed (primary and secondary) school in Las Terrazas, located in the province of Artemisa (Centro Mixto República Oriental del Uruguay). This small rural community is devoted to sustainable development and offers a unique environment in connecting with nature, incorporated even more than other schools I’ve visited. This institution gave attention to preserving and protecting the environment—both in classes and out-of-class projects.

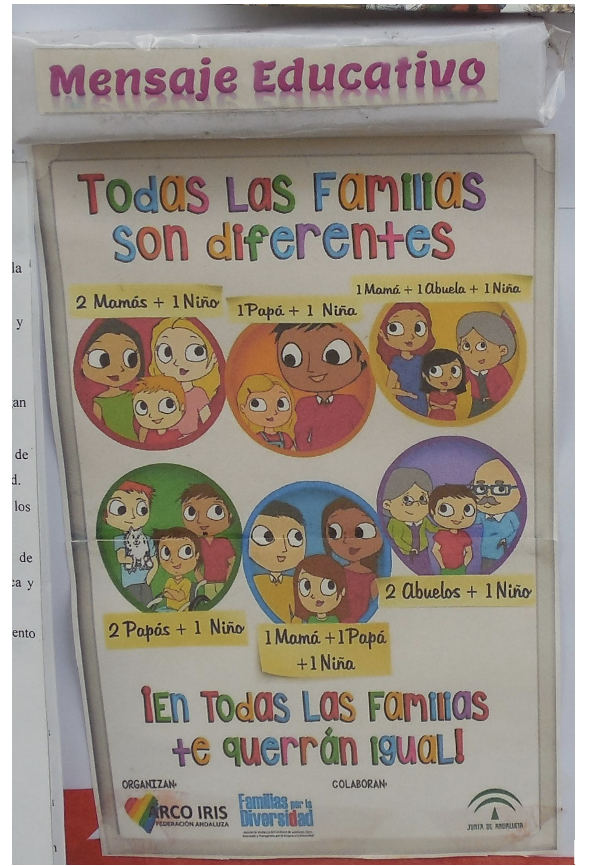

I also noticed a poster prominently displayed on a wall of the building calling attention to the reality that “all families are different.” In line with Cuba’s Families Code, which was overwhelmingly approved through popular referendum in 2022, the message is that families can be headed by a heterosexual couple, a gay/lesbian couple, a single male or female, and parents or grandparents.

I was thrilled to visit a primary school in Havana (Nicolás Estévanez Murphy). I have a long-standing admiration for José Martí Pérez (1853 – 1895), a Cuban poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, and professor, who founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party (fighting for independence from Spain’s colonial rule and to end slavery) and lived for many years in New York City. Not only did the school have the usual statue of this national hero (see photo), but each of the classrooms was labeled with one of Martí’s stories from his classic children’s volume, La Edad de Oro (The Golden Age).

I have lived mainly in urban areas in the US and Egypt and spent most of my time in cities in Cuba. But I had a chance to visit the national Agrarian University as well as the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, both located in the province of Mayabeque. I was very impressed with the academics and scientists that I met.

Like other Cubans who spoke to our group, these colleagues exuded pride in their institution’s accomplishments, despite the challenges they had faced when the blockade was strengthened during the ravages of the pandemic. I was particularly struck with some of the Institute’s research and development achievements. Their work focused on creating strains of various plants that could thrive in diverse topographical and climate conditions (including hurricanes and drought).

At one point I asked whether the speakers thought that any of the seed variants that they had created would be beneficial to farmers in the US. They said that African, Asian, European, and Latin American countries that had made effective use of their inventions. I followed up to clarify that my question was about the US benefitting, and they responded by stating the obvious that—because of the blockade—they couldn’t export their products to the US.

This led me to reflect how the US financial, commercial, and economic blockade (what some in the US call an embargo) negatively affects not only Cubans but US citizens as well. The blockade not only restricting our access to important biopharma products (for the treatment of certain cancers and prevention of amputations for people with diabetes) but also prevents us from benefitting from the achievements in the area of agricultural sciences.