For years, the mantra for advocates of unhoused people has been “sweeps kill.” Now, their tagline has science and hard numbers to back it up.

In a study focused on 23 US cities, including San Francisco, researchers from the University of Colorado School of Medicine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and several other academic institutions determined that unsheltered people who inject drugs and who are repeatedly forced out of street encampments are likely to suffer higher illness and death rates than their peers who stay put.

The report, which matches street smarts with academic rigor, was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association on April 10. The study also found higher rates of overdose and serious injected-related infections among those who are continually displaced.

Though lead analyst Samantha Nall expected high morbidity and mortality rates among this group, she was still struck by the degree to which sickness and death occur.

“I was surprised by the extent of negative health outcomes,” she said. “I think one of the things that really got me was the number of fatal overdoses and the number of non-fatal overdoses.”

To study possible end results over a 10-year span, Nall and her collaborators input data onto a series of Sims-style scenarios. In the simulation, every week, a number of people experience a change in health status such as an overdose, a hospitalization, or the beginning of treatment for opioid-use disorder.

Using the CDC’s data from its National HIV Behavioral Survey system, the researchers sorted the demographics from these models by age, gender, injection practices and injection frequency.

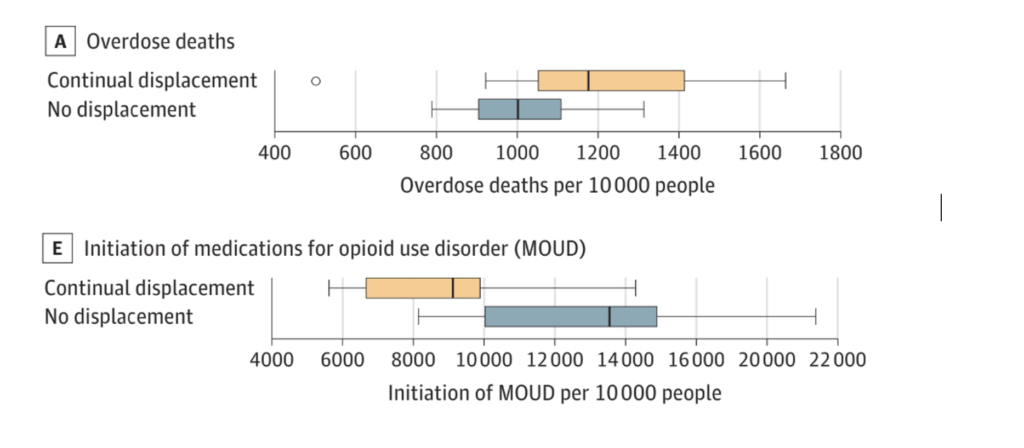

Their models projected that people who are subjected to continual sweeps are less likely to initiate opioid treatment—and are up to 24.4 percent more likely to die over a 10-year period— compared with their stay-in-place counterparts.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

The models also show an almost one-year difference in life expectancy between the two groups, as they reflect houseless people’s struggle to survive and self-medicate to cope with the trauma of street life.

These findings could prove significant as cities grapple with the persistent visibility of unsheltered homelessness and attendant behavioral health problems. Of late, San Francisco has become a poster child of that visibility—as well as how it treats its unhoused constituency.

Before closing it late last year, San Francisco operated a supervised drug-use site at the Tenderloin Linkage Center, reversing more than 300 overdoses in the brief time it was open. On that score, it succeeded in saving lives, but only 2% of overall visits resulted in linkage to services, such as shelter, housing and treatment.

Since the center closed, the city has found no replacement site for safe use, and that might have played a large role in the increase of fatal overdoses in the last year. From January to March 2023, the Medical Examiner’s office reported 200 deaths, outpacing the 142 counted in the same time frame for 2022, when the Tenderloin Center kicked into gear.

Where do unsheltered San Franciscans who use drugs go if there’s no safe place to take a hit? Most likely, they’re outside in public view. If they’re lucky, they might avail themselves of harm reduction services—like needle exchanges and naloxone distribution—that meet them where they are, so they could discreetly use them in makeshift lodging.

That is, until city crews clear their encampments and throw away their Narcan. Since the federal government recognizes naloxone as a medicine, and San Francisco’s policy is to ensure medication and other belongings collected in sweeps are stored for retrieval, then the city is violating its own “bag and tag” policy when it disposes of the lifesaving drug. A lawsuit the advocacy organization Coalition on Homelessness filed with seven homeless plaintiffs alleges that the city does just that, as a regular practice.

The risk of other injection-related illnesses concerns Felanie Castro, a harm reduction manager at GLIDE. Their organization’s program supplies clean syringes and naloxone to people who use drugs, and refers them to HIV treatment.

“If overdose deaths increase as a result [of sweeps], I hope somebody monitors them,” they said. “The last thing I want is if somebody has HIV and is missing their medication. If I’m missing my meds, then I’m transmittable, [and] then that’s another problem.”

Sweeps also further traumatize unhoused people, as Nancy Mullin, a clinical psychologist with the Homeless Youth Alliance, points out. Her work with unhoused folk in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood is built on being able to engage them wherever they are, she said.

“The relationships I build with folks in many ways are intended to address and counteract the harms that have been done to them by the systems they are subject to,” Mullin said. When her clients get displaced, she’s left without a way to provide care for them—and that could have dire ramifications.

“Sweeps disrupt the ways I am able to use my skills to address trauma,” Mullin said. “For example, leading to folks being at greater risk for more chaotic drug use and overdose.”

Leslie Dreyer, organizer of Stolen Belonging, has heard similar stories on the street. Her project has been documenting the harmful impact of sweeps on street-dwelling residents with recorded interviews, art displays and organizing public actions against the city (disclosure: This reporter is a member of the Stolen Belonging production team).

“When we say ‘sweeps equal death,’ it is not hyperbole,” Dreyer said. “We’ve even heard testimony of folks telling the workers directly that they needed to get their meds out of the belongings being seized, and the workers ignored the pleas or worse,” in some cases threatening harm.

“It is long past time for the city to prioritize caring for residents who need a home,” she said. “Not caging or clearing them and their personal belongings from sight.”

Graphs cou

For years, the mantra for advocates of unhoused people has been “sweeps kill.” Now, their tagline has science and hard numbers to back it up.

In a study focused on 23 US cities, including San Francisco, researchers from the University of Colorado School of Medicine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and several other academic institutions determined that unsheltered people who inject drugs and who are repeatedly forced out of street encampments are likely to suffer higher illness and death rates than their peers who stay put.

The report, which matches street smarts with academic rigor, was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association on April 10. The study also found higher rates of overdose and serious injected-related infections among those who are continually displaced.

Though lead analyst Samantha Nall expected high morbidity and mortality rates among this group, she was still struck by the degree to which sickness and death occur.

“I was surprised by the extent of negative health outcomes,” she said. “I think one of the things that really got me was the number of fatal overdoses and the number of non-fatal overdoses.”

To study possible end results over a 10-year span, Nall and her collaborators input data onto a series of Sims-style scenarios. In the simulation, every week, a number of people experience a change in health status such as an overdose, a hospitalization, or the beginning of treatment for opioid-use disorder.

Using the CDC’s data from its National HIV Behavioral Survey system, the researchers sorted the demographics from these models by age, gender, injection practices and injection frequency.

Their models projected that people who are subjected to continual sweeps are less likely to initiate opioid treatment—and are up to 24.4 percent more likely to die over a 10-year period— compared with their stay-in-place counterparts.

The models also show an almost one-year difference in life expectancy between the two groups, as they reflect houseless people’s struggle to survive and self-medicate to cope with the trauma of street life.

These findings could prove significant as cities grapple with the persistent visibility of unsheltered homelessness and attendant behavioral health problems. Of late, San Francisco has become a poster child of that visibility—as well as how it treats its unhoused constituency.

Before closing it late last year, San Francisco operated a supervised drug-use site at the Tenderloin Linkage Center, reversing more than 300 overdoses in the brief time it was open. On that score, it succeeded in saving lives, but only 2% of overall visits resulted in linkage to services, such as shelter, housing and treatment.

Since the center closed, the city has found no replacement site for safe use, and that might have played a large role in the increase of fatal overdoses in the last year. From January to March 2023, the Medical Examiner’s office reported 200 deaths, outpacing the 142 counted in the same time frame for 2022, when the Tenderloin Center kicked into gear.

Where do unsheltered San Franciscans who use drugs go if there’s no safe place to take a hit? Most likely, they’re outside in public view. If they’re lucky, they might avail themselves of harm reduction services—like needle exchanges and naloxone distribution—that meet them where they are, so they could discreetly use them in makeshift lodging.

That is, until city crews clear their encampments and throw away their Narcan. Since the federal government recognizes naloxone as a medicine, and San Francisco’s policy is to ensure medication and other belongings collected in sweeps are stored for retrieval, then the city is violating its own “bag and tag” policy when it disposes of the lifesaving drug. A lawsuit the advocacy organization Coalition on Homelessness filed with seven homeless plaintiffs alleges that the city does just that, as a regular practice.

The risk of other injection-related illnesses concerns Felanie Castro, a harm reduction manager at GLIDE. Their organization’s program supplies clean syringes and naloxone to people who use drugs, and refers them to HIV treatment.

“If overdose deaths increase as a result [of sweeps], I hope somebody monitors them,” they said. “The last thing I want is if somebody has HIV and is missing their medication. If I’m missing my meds, then I’m transmittable, [and] then that’s another problem.”

Sweeps also further traumatize unhoused people, as Nancy Mullin, a clinical psychologist with the Homeless Youth Alliance, points out. Her work with unhoused folk in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood is built on being able to engage them wherever they are, she said.

“The relationships I build with folks in many ways are intended to address and counteract the harms that have been done to them by the systems they are subject to,” Mullin said. When her clients get displaced, she’s left without a way to provide care for them—and that could have dire ramifications.

“Sweeps disrupt the ways I am able to use my skills to address trauma,” Mullin said. “For example, leading to folks being at greater risk for more chaotic drug use and overdose.”

Leslie Dreyer, organizer of Stolen Belonging, has heard similar stories on the street. Her project has been documenting the harmful impact of sweeps on street-dwelling residents with recorded interviews, art displays and organizing public actions against the city (disclosure: This reporter is a member of the Stolen Belonging production team).

“When we say ‘sweeps equal death,’ it is not hyperbole,” Dreyer said. “We’ve even heard testimony of folks telling the workers directly that they needed to get their meds out of the belongings being seized, and the workers ignored the pleas or worse,” in some cases threatening harm.

“It is long past time for the city to prioritize caring for residents who need a home,” she said. “Not caging or clearing them and their personal belongings from sight.”

This story also appears in the next edition of the Street Sheet.