An elemental part of hip-hop culture, graffiti art has always had a tenuous relationship with authority. When the ’90s arrived, graffiti artists did their best to remain prolific—and more importantly, seen—in the wake of increased criminalization and cries of vandalism. Because who knew how long a piece might stay up on a wall before it was whitewashed?

Graffiti zines offered a place for pieces, throwups, and handstyles to live on no matter who wanted to take them down. They also served as a place to forge deep national and international networks of artists who strove to connect and spread their elaborate work far and wide. Artwork was exchanged by mail and then industriously photocopied, collaged, and pieced together in zines to showcase the best graffiti art from multiple locales in creative, insightful, and provocative ways. Like one final analog shout before the world plunged into the digital realm.

Fascination with this pre-Internet era cultural exchange prompted Dogpatch nonprofit Letterform Archive’s newest exhibit “Subscription to Mischief: Graffiti Zines of the 1990s” (through November 2023; an online gallery will be launched soon). Letterform is devoted to print arts in all forms, and this show is a vibrant, loud, and fiercely countercultural dispatch.

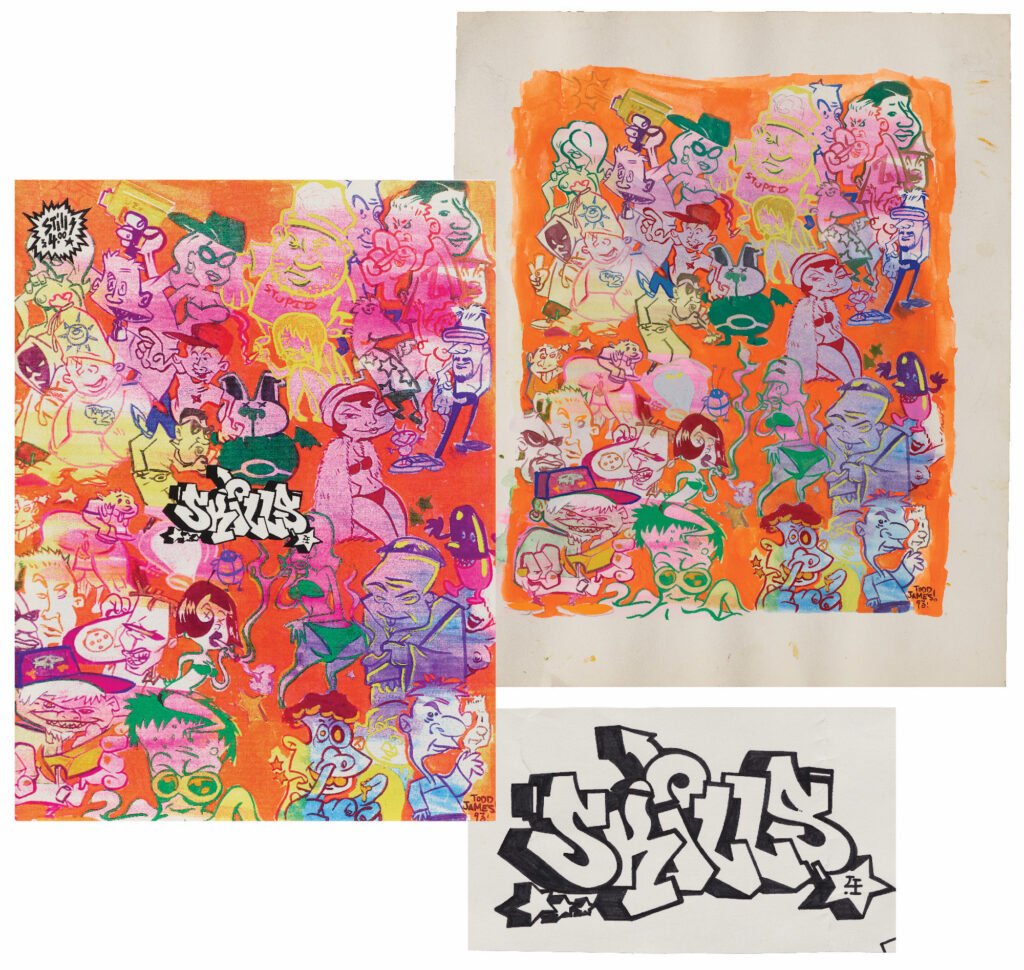

At the center of “Subscription to Mischief,” are the seven issues and archived content of influential Skills magazine, which ran from 1992-1995 and was put together by exhibit co-curator Greg Lamarche, aka Sp.One. Based in Boston at the time, Lamarche created Skills using art and flicks—photographs of graffiti art—sent in by aspiring contributors from around the country and beyond. The puzzle-like fashion in which Lamarche laid out the artworks alongside each other on the pages of Skills creates an immersive visual world: Like a magic eye illusion that’s come to life without having to cross your eyes.

The exhibit flows chronologically through the ’90s, first taking you through the bones of Skills’ seven issues. Where for every lesser known or ephemeral graffiti writer that Lamarche featured, there’s also notable names like Shepard Fairey and exhibit co-curator and graffiti historian David Villorente, aka Chino BYI. Fairey’s 1993 contribution is a sketch of a small bottle of “Growth Tonic” with Andre The Giant’s face emblazoned on the vial—one of the figureheads of his OBEY empire’s early work. Lamarche photocopied it onto the fifth issue’s first page alongside a photo of The Pharcyde holding up past issues of Skills, a reminder of graffiti’s inextricable ties to hip-hop culture even as both became radically commercialized.

The archived letters the Skills community sent to Lamarche, which he compiled here for display, are just as vibrant as its art. Along with a flick or piece, artists from across the country would describe their respective cities’ canvases. There’s a letter and flick from a graffiti writer in Finland claiming that it’s the northernmost graffiti art in the world. A note from Seattle tells about how “The huge port city is caked with FR8s,” referencing the many trains that were ripe to be graffiti bombed.

The colloquialisms in the letters are marvelous. Cats wrote like ’90s hip-hop kids spoke, and reading through it it all is like cracking open a transformative time capsule. It shows the ease in communication within the graffiti community that led to the proliferation of the artform. Skills was in the eye of the storm in the 90s, topping out at 10,000 copies in circulation by its seventh issue, even counting Tower Records (RIP, sweet jewel) as one of its main distribution points.

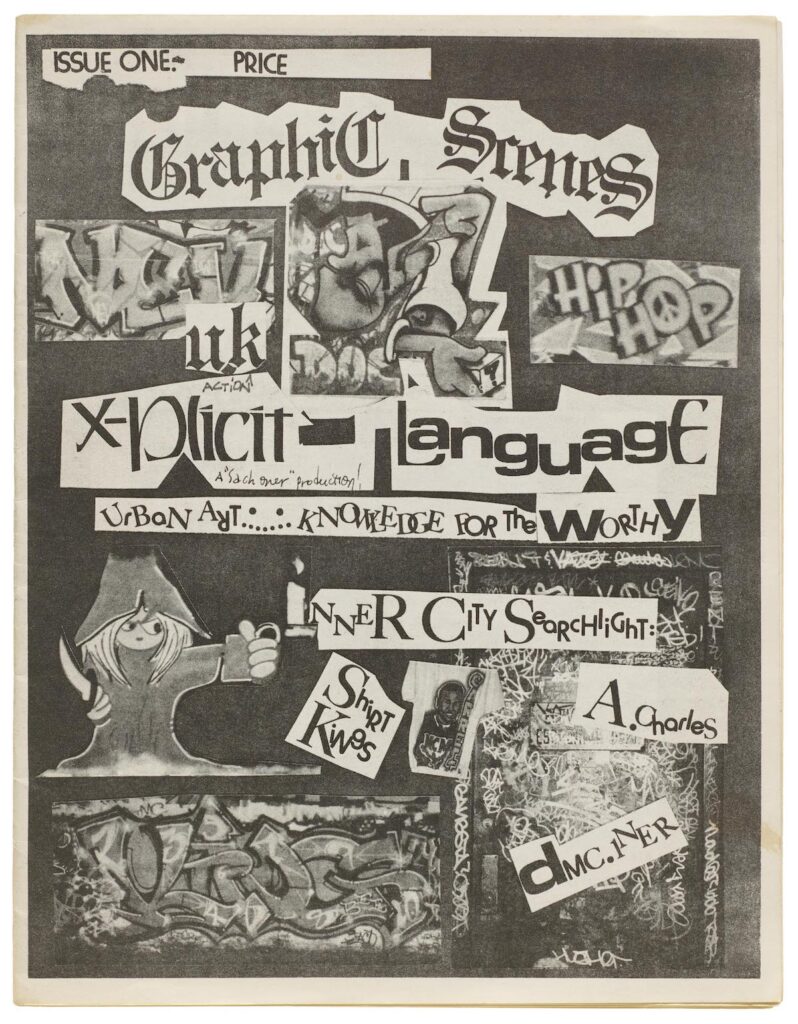

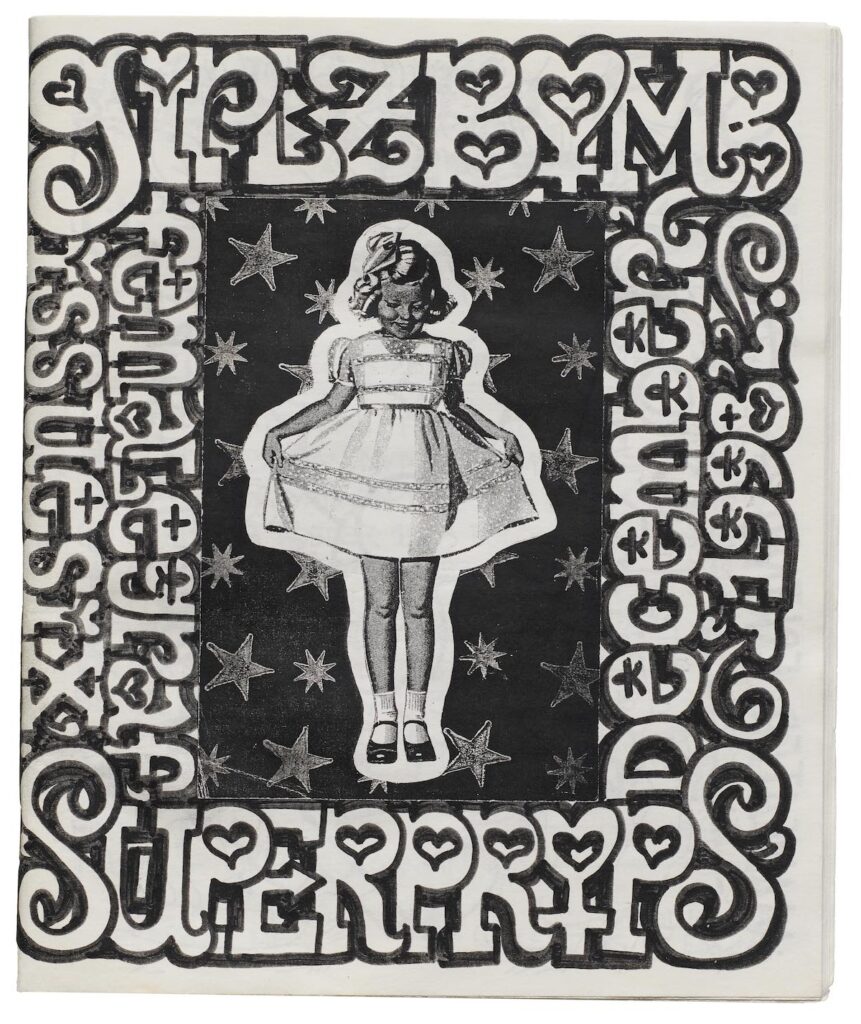

Creators behind other zines would also write in pledging their allegiance to Skills and the overarching influence of these and other zines comprise another part of the exhibit altogether. “Subscription to Mischief” organizers Lamarche, Villorente, and Letterform’s Kate Long Stellar and Kel Troughton also highlight other influential zines from the era, like the late ’80s-established Can Control (there’s a Simpsons reference in here somewhere), Graphic Scenes & X-plicit Language (created by The Boondocks writer, TV producer, and hip-hop renaissance man Sacha Jenkins), and the presciently titled IGTimes (not that IG, but rather International Graffiti Times).

What especially struck me about the presentation of “Subscription to Mischief,” is the interconnectedness of the disparate timelines and locales. A prime example is how Villorente’s early submissions at the onset of Skills ultimately lead to the graffiti column that he eventually curated for The Source magazine. There’s a distinct throughline in the exhibit tracking graffiti from the start of the decade into its latter parts that runs parallel to the growth of hip-hop culture.

The Bay Area finds its way throughout “Subscription to Mischief” as well. Both in art (early ’90s The Bomb Hip-Hop Magazine) artists (Twist, Jocelyn Superstar, Spie TDK, Mike Giant, Juice, Reminisce, Josh Lazcano/Amaze, Some/Nate Smith), and an endless sea of flicks along a long hallway wall. I dug trying to place where in the city certain photos were captured, spotting a wall on Upper Market that I bike past on the regular in one and a spot in the Mission in another.

These days, while graffiti art still exists in the wild, it’s online mediums that serve to vault them beyond the confines of their respective origins. “Subscription To Mischief” transports us back into a simpler and more, er, inefficient time by today’s standards. But the impact of said inefficiency is remarkable. It captures that feeling of sending and receiving a letter in the mail that contained much more than just words, and how it told a story through art; anticipation and hope of that non-immediate sense of gratification, and how this mechanism built and expanded an entire cultural exchange of graffiti art and the undeniable collective energy that lives on.

SUBSCRIPTION TO MISCHIEF: GRAFFITI ZINES OF THE 1990s runs through November 2023 at Letterform Archive Gallery, SF. More info here.