Sérgio Dias sunk into a chair, and my heart sunk with him. On a whim, I’d decided to shell out 50 bucks to see Os Mutantes, the great Brazilian psych band, at the Chapel. It was the presence of Mad Alchemy that really sold me—every lover of live music should catch one of their endlessly complex and ever-shifting light shows at least once during their lifetime—and I’d met a Rhode Islander in town for the weekend whom I felt a personal mission to convince San Francisco was far from dead. Yet Dias is the last original member of the band, after singer Rita Lee passed away in March at age 75. And the last time I’d seen a band with one original member, I was sorely disappointed: Parliament-Funkadelic, with George Clinton brooding in a swivel chair and essentially serving as the hype man to an anonymous cabal of pros playing his music.

Yet as soon as the band revved up, my doubts were obliterated. Dias remains a nimble guitarist and flexible singer, and this mostly younger version of Os Mutantes is one of the strongest live psych-rock bands I’ve seen. The band’s later material is about what you’d expect from ‘60s rabble-rousers aging into the dumpster-fire era: politicized but not particularly urgent, dutiful instead of genuinely angry. But they backed it up with a squall of howling-wind psychedelia, and their early material remains unimpeachable, especially “Bat Macumba,” a piece of music liable to rearrange the heads of anyone in a room who hears it. (Not long before the show, “Bat Macumba” came on the playlist at my work, and two separate people wondered aloud what “that sound” was. If you’ve heard the song, you know which sound I mean, and if you haven’t, please remedy that as soon as possible.)

Os Mutantes was not the only legendary Brazilian act I had the chance to see perform recently. You might know Hermeto Pascoal from video clips of the white-bearded avant-jazz legend that have circulated on the Internet: sitting in a lagoon with his musicians making sounds with the water, or maybe smoking a cigar while playing a dissonant keyboard solo with his remaining hand. In fairness, I knew him second-hand as well. Miles Davis’s Live-Evil contains three of his compositions, and Pascoal, who shares the sobriquet “The Sorcerer” with Davis, is one of the few musicians the latter curmudgeon copped to respecting. When the opportunity arose to see him at the UC Theatre in Berkeley, I went mostly because of unanswered yearnings for live avant-garde jazz—and to see an 86-year-old vanguardist on what could be his last tour.

Pascoal also spent most of the show seated. Unlike Dias, he spent very little of that time playing. The sorcerer had a bench set out for him, and he spent most of the set time conversing with an attendant and giving cryptic cues to his musicians, sometimes sitting out entire songs. But Davis didn’t do much more than that during some of his ‘70s sets, whose recordings constitute some of the greatest music ever made, even while Davis himself was nearly incapacitated after a car crash. And Pascoal’s performance—more accurately, his band’s performance—ranks among the most technically dazzling sets I’ve ever seen. I was trying to count what time signatures some of the songs were in, but eventually I gave up and concluded it didn’t really matter. This was party music, anyway: avant-garde, yes, but a shouted “hey!” from the band members said as much as a thousand notes. Ask anyone who’s been to a Bulgarian wedding and they’ll tell you music doesn’t have to be comprehensible to be groovy.

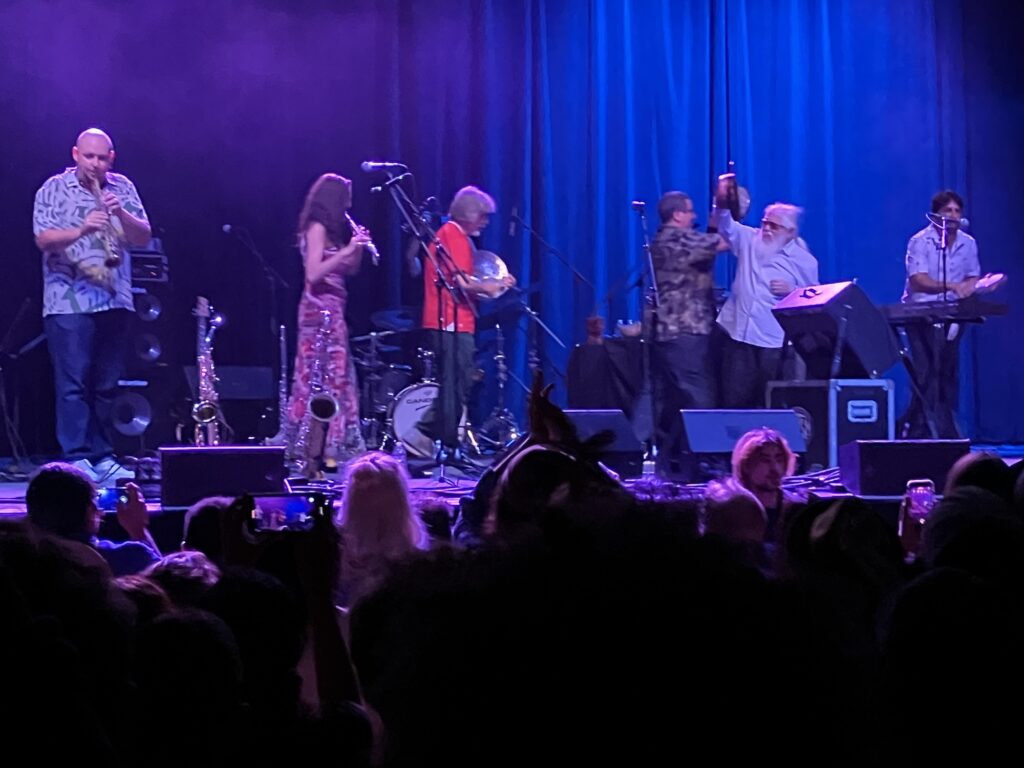

There was no guitarist—just two keyboards (including Pascoal’s), an affable bassist who doubled as a purposeful vocalist, a killer drummer, a percussionist, and Pascoal’s loyal attendant, who in a regal flex did most of the speaking for the silent sorcerer. Though the Jazz is Dead collective promoted the show and usually hires out their own musicians to back up the legends they promote, this evening featured Pascoal’s usual backing band. A highlight of the evening was the percussionist’s solo, centered on a sound a little like the doglike Brazilian cuica but harsher and raspier. What could it be? It turned out to be a rubber pig. The presence of that pig speaks to the confidence of musicians whose gifts go unspoken and who thus feel no great need to take themselves seriously. Pascoal isn’t a dark magus like Miles but an affable Gandalf type, and even as a silent and mysterious presence on stage, he seemed like a happy-go-lucky guy.

So was it worth going to a Hermeto Pascoal show to mostly see other people play? For me, absolutely—the music is the abiding memory, unlike at P-Funk, where the exploratory spirit of that band’s near-untouchable ‘70s and ‘80s heyday had been replaced by dutiful and professional performances of the band’s hits. I wonder if the idea that the credited artist has to be the one doing the most work or that the music is inauthentic or a ripoff isn’t a symptom of American capitalist resentment. I remember when Beyoncé lost the Grammy to Beck and the argument was that she only played one instrument on her album to Beck’s dozen or so, to which my reply was: Would the Beyoncé album deserve a win if it were credited to Beyoncé, Boots, Miguel, The-Dream, etc.? And if it took Pascoal to put a band like that together to play music like that, it’s fair to say he can be as sedentary as he wants.