Still teaching in his late 80s, Professor Hugh Cohen is all over the new book Cinema Ann Arbor, whose author Frank Uhle will appear at Oakland’s Shapeshifters Cinema Fri/21 for a program of conversation (with filmmaker Danny Plotnick) and relevant archival films. A prominent Ingmar Bergman scholar, among other things, Cohen was my own favorite teacher at the University of Michigan four decades or so ago, and we’ve stayed in touch.

Visiting him some years back, I asked how his students today were different from those of the past. He said that while they were “as bright as ever,” and as absorbed by the art form, they now typically arrived without any prior exposure to, or even curiosity about, film history—their depth of knowledge seldom went further back than movies made during their own as-yet-short lifespan.

This was flummoxing to me, as theoretically at least, they had all of cinema at their fingertips, readily accessible in ways (from Blu-rays to streaming, including a near-infinite amount of variably legal free content online) I couldn’t have dreamt of as a small-town teenager in the late 1970s. How could they not take advantage of that bounty? Somehow, Prof. Cohen told me, it just hadn’t occurred to them…at least until they took one of his classes.

Yet even in pre-cable/pre-VCR Western Michigan, it was possible to get a thorough cinematic education, if you had the obsessive will. Not only where there multiplexes for new mainstream releases and drive-ins for schlock (plus a lone arthouse about an hour’s drive away), but the handful of local TV stations available provided a fair gamut beyond network programming: One had the Warner Bros. and MGM libraries on tap to program a weekday morning “Early Show” of “golden age” Hollywood films, another showed cult horror movies late Saturday night.

However cut and/or panned ’n’ scanned, those stations provided a steady diet of films from the 1950s through early ’70s to fill out their schedule. And PBS had a retrospective of Janus Film holdings (basically offering a course in Foreign Cinema Classics 101), in addition to a silent showcase and the short-lived but eye-opening International Festival of Animation, which introduced many viewers to the likes of Jan Svankmajer.

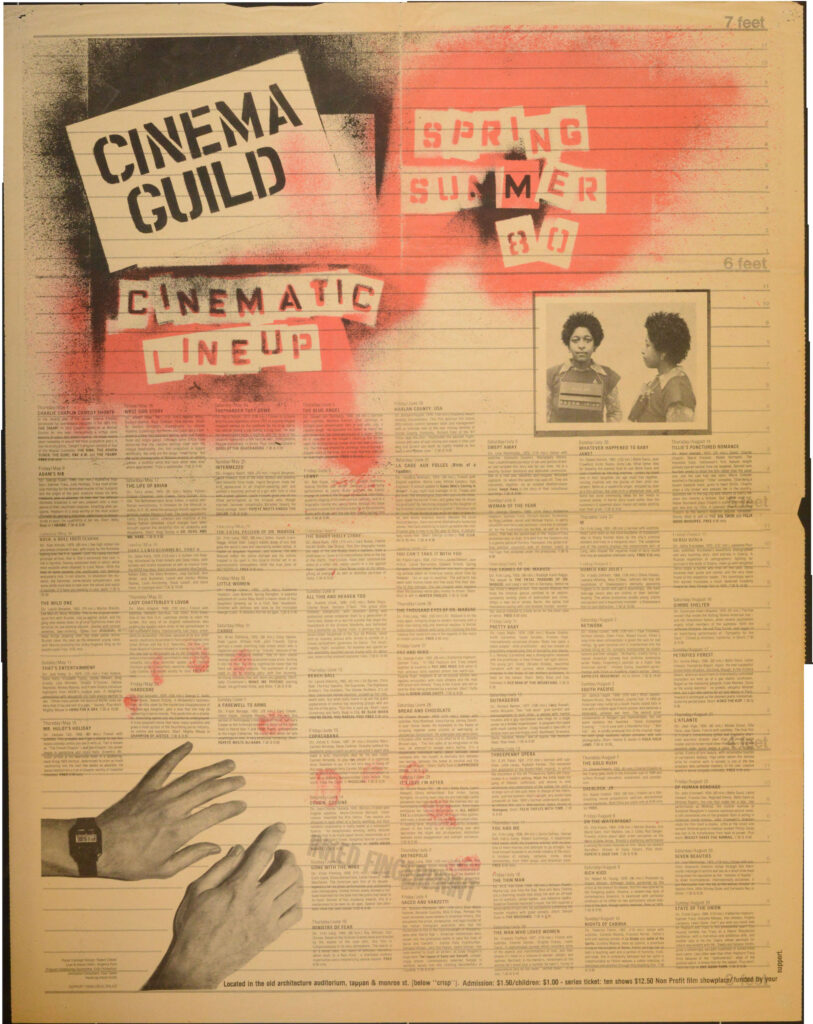

So, arriving as a U-M freshman in 1979, my knowledge of the medium wasn’t exactly limited to Smokey and the Bandit. Still, there was a whole lot of additional catching up to do, and as Cinema Ann Arbor details, the campus and surrounding town were then a pretty stupendous place to do so. Beyond the generous supply of local commercial houses showing new mainstream and arthouse releases, university film societies were so plentiful, and prolific, that in 1983 it was estimated they averaged 500 individual programs… per semester.

These ran a heady gamut of foreign and Hollywood classics, auteurist excavations, overlooked recent indie or imported features, experimental work, political documentaries, culty “midnight” selections (I still remember being shocked when my Michigan Daily colleague turned current fellow Variety contributor Owen Gleiberman lit up a joint right outside a campus screening of Woody Allen’s Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex), et al. Then there were marathon six-hour-plus nights at the annual 16mm Ann Arbor Film Festival and its rougher-edged 8mm sibling. I basically “majored” in watching movies, often to the detriment of my formal studies.

It was an extraordinary environment for serious film lovers that happened to be at its absolute peak. Back then, nobody had a TV (let alone a PC) in their dorm room, and even the sets in communal lounges were seldom used. Yet by the late 1980s, all that was rapidly changing. The film societies were in money-losing freefall, soon to die out entirely. As ubiquitous as movies on campus had been for years, they abruptly became obsolete, though institutions like the Ann Arbor Film Festival soldiered on (albeit trading 16mm for digital formats).

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Subtitled “How Campus Rebels Forged A Singular Film Culture,” Uhle’s coffee-table-scaled tome details an exhibition history that stretches back as far as 1930, though it only really flourished with the explosion of film consciousness in the Sixties. Then it went nuts: Andy Warhol brought the Velvet Underground and the multimedia Exploding Plastic Inevitable show to the festival; legends from Frank Capra to Robert Altman, Frederick Wiseman and Timothy Carey were invited for retrospectives; film society staff made their own avant-garde efforts; censorship battles of national import were fought over local exhibition of I Am Curious (Yellow) and the like.

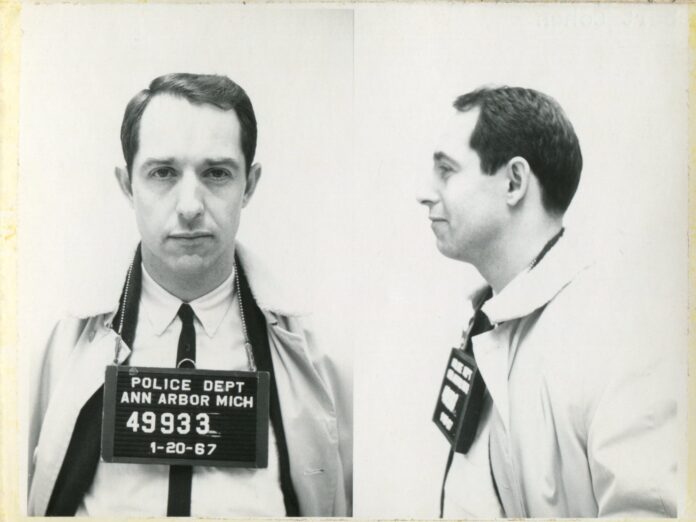

Before reading Uhle’s book I hadn’t realized, or had forgotten, how extensively Prof. Cohen was involved with these organizations, as ongoing supporter and sometimes a co-founder. (He even got arrested for showing Jack Smith’s notorious Flaming Creatures.) But I do remember finding out later that he’d watched me freak out watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre the first time (yes, it was a class assignment). Not to mention the experience of seeing Curt MacDowell’s Thundercrack one Halloween, having no idea of its contents beyond “this sounds fun”… then watching as my good sport of a freshman roommate sat squirming through its B&W camp Gothic melodrama, in which variably attractive actors engaged in highly explicit acts all along the Kinsey scale.

Well, you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone, and while I certainly appreciated Ann Arbor’s celluloid bounty at the time, it is only in retrospect that it’s clear how exceptional that was. There are interviewees in Cinema Ann Arbor who opine that for a while there was arguably no superior film-watching climate in the entire nation, in terms of density/diversity of programming and ease (not to mention low cost) of access.

While there is definitely something to be said for a latterday world in which one can find just about any obscure feature with a few keyboard strokes, that doesn’t necessarily translate into greater exposure. Film buffs seemed to adventure further and more frequently when they had to make a real effort to do so, attending one-time-only screenings and such. How did we get to a place where practically everything is readily available, yet your average gung-ho college film student may well know nothing about the medium’s “distant” past beyond Star Wars?

Along with discussing Cinema Ann Arbor, Uhle will present a selection of shorts tied to that history from the 1960s through 80s, including an early work by his interviewer Plotnick. For more info on the Fri/21 8 pm event, go here.

While at U-M, I neglected to take a course in Eastern European Cinema by Prof. Herb Eagle—because it was regularly over-full, I think. But several friends did, and I benefitted by going to a fair number of the connected screenings that (like most such) were shown in cooperation with the campus film societies, thus getting a first exposure to various personal favorites like Vera Chytilova’s Daisies. Just about the only surviving venue where you can get an equivalent experience these days is Berkeley’s BAMPFA, which this week commences a retrospective series honoring another pioneering female Soviet bloc filmmaker.

Comprised largely of 35mm prints from the institution’s own collection, The Enchanted Yuliya Solntseva pays tribute to a long career that stretched from early acting gigs to behind-the-camera assistance of a famous director spouse, to her own impressively ambitious solo works after his demise. A Moscow native, Solntseva had barely started a career in theater when at age 23, she was chosen for the title roles in two major screen productions of 1924. As Aelita, Queen of Mars, her bug-eyed space vamp presides over sci-fi sequences that turn out to be an Earthly modern-day character’s dream. A century later, the film’s fantastically odd sets, costumes and gestural vocabulary remain a surviving highlight of the Russian Constructivist school of abstract art. Anticipating both Metropolis and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T, it’s become a cult favorite.

Less well-known abroad is The Cigarette Girl from Mosselprom, in which her street hawker (as boyishly pert as Jean Seberg in Breathless) is an unpretentious sort who nonetheless rivets the competing attentions of several suitors, including a buffoonish office worker, a cameraman, and a visiting American fatcat. This comedy owes something of its brash, jaunty urban tenor to Hollywood comedies of the era. But it also sports an earnest optimism—the USSR was officially just a couple years old (though the Tsar had been overthrown in 1917), and the Soviet experiment still seemed more liberating than oppressive. What these two wildly different features share, beyond Solntseva, is a near-complete lack of the dogma that would eventually have a suffocating, censorious effect on state-approved arts.

She married the Ukrainian filmmaker Aleksandr Dovzhenko, and at the end of the decade abandoned acting for assistant directing, primarily on his projects. Her last onscreen appearance was in 1930’s Earth, a drama of farm collectivization whose poetical intensity of image and montage has long ranked it among the highest achievements of cinema, in the USSR and beyond. By the time of Aerograd (1935), however, Stalinism was beginning to stifle even a talent as bold as Dovzhenko’s. This similar story of peasant resistance to Communist progress (here at a Siberian outpost) has passages of stunning physicality on land and in the air, but also frequently stops still so characters can deliver stiffly propagandizing speeches. The idealogical straitjacket is purportedly yea-tighter in the Stalin-commissioned 1939 Shchors, though on the plus side, Solntseva was now credited as full co-director.

During WW2, she and her husband were tasked with making documentaries about the war effort, including the presciently titled Ukraine in Flames. Afterward, they like every other high-ranked artist and functionary were subject to the increasingly paranoid whims of Comrade Josef, though unlike many, that did not lead to the gulag. It was only several years after that despot’s death in 1953 that they were given the go-ahead for the first in a “Ukrainian trilogy” of ambitiously scaled dramas traversing 20th-century history, encasing specific incidents in a stream-of-conscious narrative structure and visual lyricism not far from the latterday Terrence Malick.

But Dovzhenko himself died in 1956, leaving his widow to direct the films alone. 1958’s Poem of the Sea, about a general revisiting his collective-farm village of birth as it’s about to be flooded by a dam project, often feels like a pedantic promo for the Khrushchev era—albeit regurgitating the same old promises of progress in exchange for proletariat sacrifice as before. She won the Best Director prize at Cannes (the first woman to do so) for 1961’s The Story of the Flaming Years, which opens the BAMPFA series this Fri/21. Sporting an idealized Everyman soldier hero so eager to kill and be killed for Mother Russia he seems almost a patriotic cartoon, it has sprawling battle sequences and rhapsodic passages wrestling against an imposed doctrinaire heavy-handedness.

But Solntseva comes into her own with series closer (on August 27) The Enchanted Desna, a widescreen symphony of memory—primarily Dovzhenko’s rural Ukraine childhood—whose visual poetics and narrative abstraction locate an inspired equivalent to the aesthetic purity of Earth. She continued directing as late as 1980, passing away at age 88 in late 1989—one wonders if she was aware the Iron Curtain was on the brink of toppling just then.

Out of the Vault: The Enchanted Yulia Solntseva runs Fri/2-Sun/Aug. 27 at BAMPFA in Berkeley, for more info, go here.

Much on the sillier side of things, there are other events of interest to cineastes this week. Following hot on the heels of two days pairing two old-school repertory calendar perennials (Brazil and Zardoz, Wed/19-Thurs/20), the 4-Star is hosting a weekend-long UltraFest (more info here), with movies, TV episodes, giveaways, toy/art vendors, special guests et al. paying tribute to the Japanese superhero and his international multimedia empire.

Though not so prominent in the West (albeit enough so to warrant a 1987 Hanna-Barbera cartoon), Ultraman was at one point the third most popular licensed character in the world. It’s generated billions of merchandizing-revenue dollars since being created in 1966. New film and TV adventures are still being churned out, as well as unauthorized imitations—the latest Shin Ultraman feature will be screened at the event. In fact, what I thought was my own strongest memory of Ultraman in fact turned out to be Infra-Man, a demented 1975 Hong Kong ripoff of the franchise.

In a not-dissimilar spirit of camp nostalgia, there’s Dario Russo’s Italian Spiderman, a 40-minute featurette drawn together from 10 original YouTube episodes that plays Oakland’s New Parkway on Fri/21. Made in 2007 Australia, it purports to be a vintage Eurotrash action fantasy in the mode of 1960s Italian superhero and superspy cheapies, as well as 1970s Turkish exploitation films, and other retro psychotronica. Deliberately cheesy but also amazingly resourceful on slim means, it has acquired its own well-deserved cult following as an esoteric spoof. More info here.