“Let me put this down for a second,” said William Basinski last Friday evening, just before his wine glass landed on the table with a grand thunk. Just about anything sounds dramatic in Grace Cathedral, whose famous reverb has attracted great musicians and artists since its completion in 1964; Duke Ellington and Vince Guaraldi performed and recorded there within a year of its completion, and throughout 2024 it’s hosted Reflections, a series pairing live performances by ambient and new age greats with mind-bending visuals that transform the yawning Episcopalian cathedral into an underwater wreck or psilocybin fantasia. The NYC-rooted, LA-based Basinski was the star of the latest installment, a cutup whose irreverent wisecracks contrast sharply with the murmured thank-yous that usually pass for banter in this genre. “It’s very dahk,” he complained, fumbling with his equipment before the spectral sound of his trademark tape loops began to fill the space.

Basinski’s Arcadia Archives tour focuses on loops from an archive going back nearly 40 years. He’s been plundering this vault for decades, making the decay of the tapes a crucial part of his practice. His most acclaimed and notorious project is 2003’s The Disintegration Loops, which the composer was assembling from rusted tape loops when he saw the planes hit the Twin Towers from his window; the decay of the tapes became a stand-in for the loss of life, or maybe the decay of democratic American values, really whatever thoughts on 9/11 you brought to it. He’s a bit of a huckster—he looks the part, half club kid and half carnival barker—and it’s as much his chutzpah and canniness that gets him on those “acclaimed” lists as the power of his loops. His albums are usually divided into lengthy tracks that run over 20 minutes, but they appear on streaming services divided into short micro-tracks, the better to rack up revenue from individual song streams. You have to respect the hustle, especially when his music hits such a sweet spot.

After the performance, Basinski referred to the piece as a “requiem mass” in tribute to his mother, who had recently passed away. At first, I thought this was more after-the-fact context—this wasn’t in the program!—and then I thought about how the inexorable passage of time and all the other themes in Basinski’s music get less abstract as you and your loved ones get older. There was a time when I listened to the Caretaker’s Everything at the End of Time series to fall asleep, or to enjoy music that sounded as little like music as possible as I lost myself in expanses of static. But the (also contentious) gist of Leyland Kirby’s famed project is that the decay of the vinyl records that make up his source material stand in for the decline of human cognitive functions, and that the project itself is suffering from memory loss. Soon came the point when Everything at the End of Time became about my parents and I couldn’t just treat it as casual listening. There will come a time when it’s about me, but that’s a discussion for later.

Maybe Basinski intended Arcadia as something else, and then it got a bit more real than even he anticipated after his mother’s passing. Maybe the same thing happened with The Disintegration Loops when the planes hit. Either way, the music really does seem to be charged with ghosts. The performance was based on a three-note piano loop; as the piece progressed, the third note became blotched, faceless, hollowed out, as if Basinski had been slowly whittling away at it with a knife. Occasionally a swell of hiss would consume it, then it would emerge reborn from the silence before the same process took hold again. Basinski prefers austere lighting, and for most of the set, he was bathed in a ghostly blue-gray glow; when the tape hiss began to take hold, Eric Epstein’s lights would start to waver, making the cathedral itself look as if it’d turned to jelly.

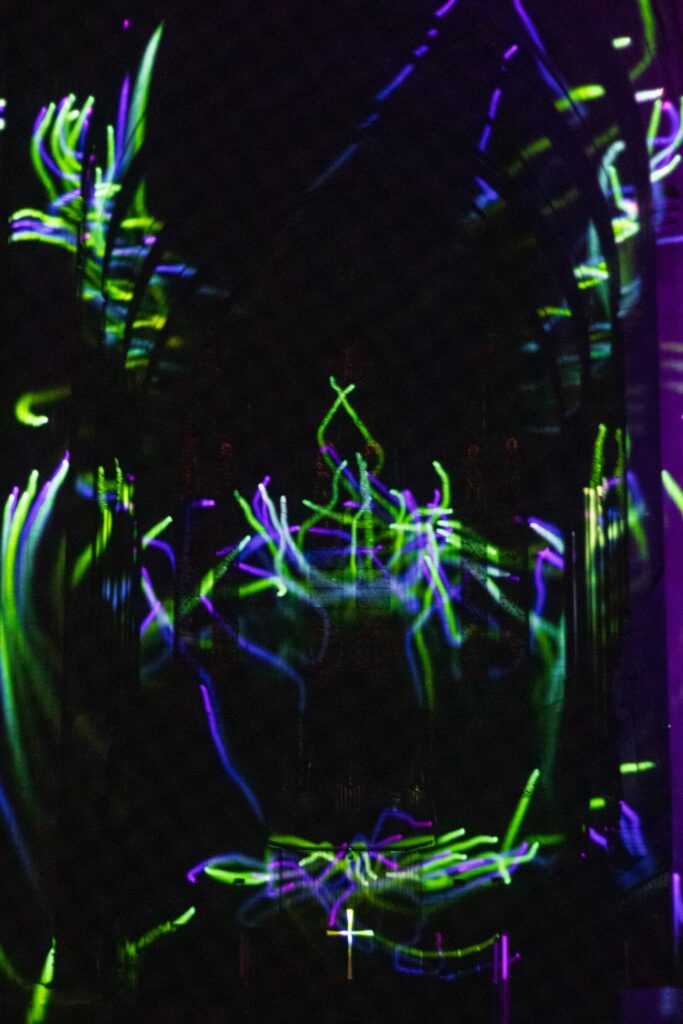

The opening act was Flore Laurentienne, a project comprising French-Canadian composer Mathieu Gagnon and a small cadre of string players, sweeping through in the wake of latest album 8 tableaux. Whereas Basinski’s music was austere, Gagnon’s was grand and sentimental, all yearning strings and plaintive synth patches, inspired by the wilderness of the composer’s native Quebec. It fell somewhere between the elemental churn of John Luther Adams and the floral filigrees of Harold Budd (now that would’ve been a Reflections to reckon with). Rather than projecting impassivity as Basinski did, Gagnon made unapologetically weepy music, and Epstein matched it with one of the most moving light-shows I’ve seen: thousands of little glow worms, each one snaking its way across the pillars towards oblivion.

After the initial “wow” factor of the light show faded, I became very invested in these worms and their random and lonely motions across the cathedral walls. I started to think of them as sea-monkeys, small creatures who were living and dying for our entertainment, and when they began to coalesce in certain corners and squiggle more furiously as the show went on, I found myself relieved. This was the next stage in their life cycle.

I wonder if these kinds of pass-the-bong associations aren’t necessary to appreciate paying to sit in a pew for hours and listen to music that would test the patience of most 21st-century audiences. I wonder if to enjoy this music, you have to make the same leap of faith one has to make to ascribe to a religion. Yet that leap has never been hard for me to make personally. I’ve always been moved by the vastness of time and space ever since I was a kid staring wide-eyed out the window of my parents’ car, and nothing does a better job of evoking that feeling for me than the glacial crawl of ambient music. When I walked outside, the plaza outside Grace Cathedral was ensconced in fog so thick it was hard to even see the buildings across the street. I sometimes say that I worship the thing that stares back when I look into the fog. If you know what I mean, I think you’ll understand what keeps me coming back to this stuff.