In 1946 after serving in World War II, photographer Minor White came to San Francisco to teach at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) at the urging of his friend Ansel Adams.

White, one of the founders of the influential Aperture magazine, (along with Adams, Dorothea Lange, and others) planned to do a photographic series, City of Surf, which was never realized. Today, some of these photos make up the show “San Francisco Photographs by Minor White” at the California Historical Society through January 22.

Director of exhibitions Erin Garcia thinks the photographer just wanted to show what he saw while walking around with no particular agenda, open to what he might see.

“He is observing and trying to take kind of a neutral stance,” she said. “I don’t think he’s romanticizing what he’s seeing or condemning it. He is seeing a city in the midst of a lot of change.”

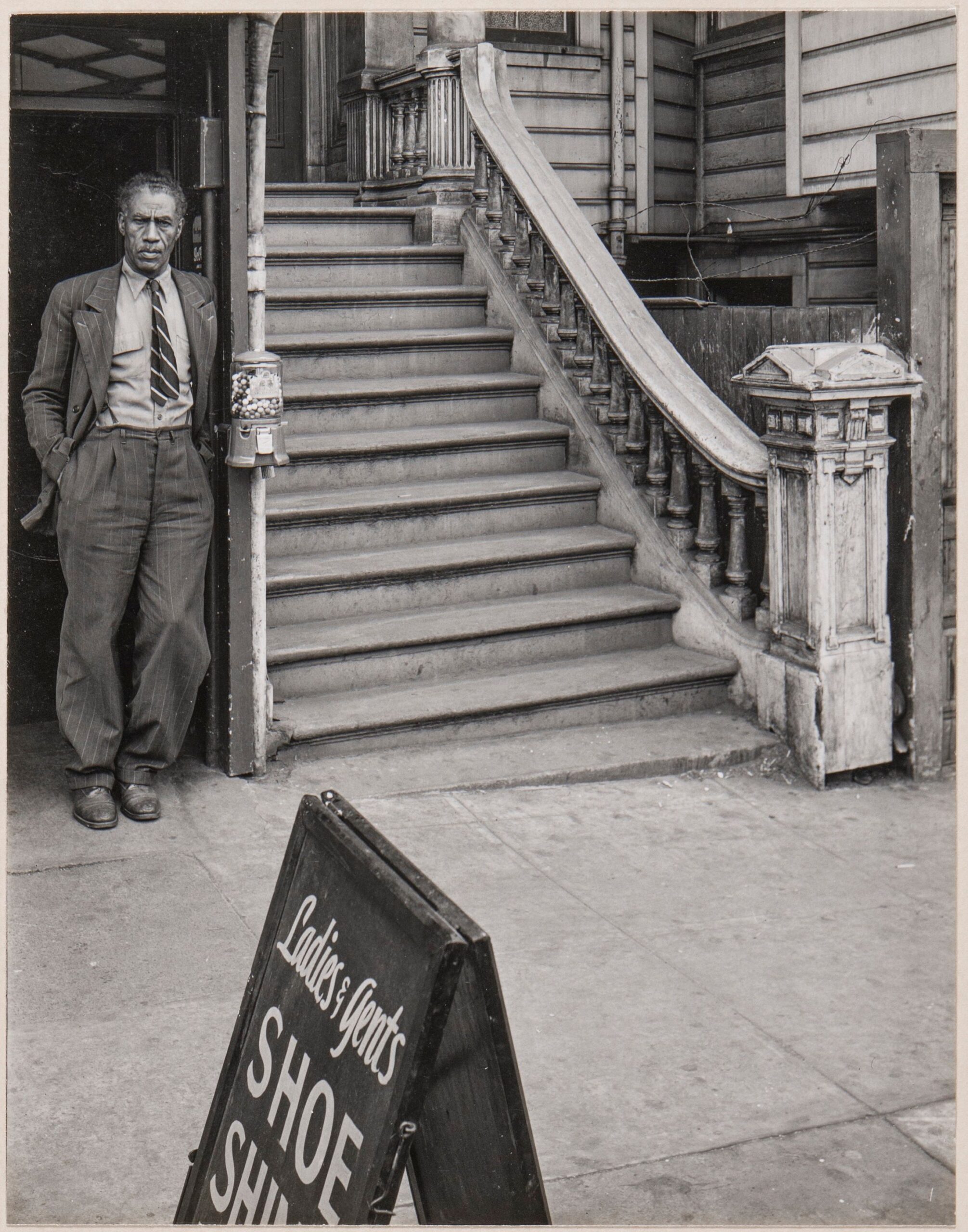

In the 59 photos culled from the collection of 473 vintage gelatin silver prints (along with their original negatives) that White left to the historical society in 1957, we see the city in a post-war boom. Houses are being built in the Outer Sunset next to sand dunes, workers pour cement for sidewalks and unload produce trucks. There are photos of businesses on Fillmore Street such as Juhl’s Pet Supply, where the horsemeat is sold (it’s for animal consumption only) and the Nippon Pool Hall. There’s a photo of children playing in the street, and one of a horse-drawn cart going down Potrero. Garcia says she finds White’s photos of a changing city and the demographic shifts insightful, such as the images of women working downtown and neighborhoods becoming more diverse.

“He’s really seeing kind of the layers of the city” she said. “There’s photos in Chinatown of buildings being demolished for new construction, so what he’s showing is a new city taking over the older city.”

White became known for compositions that suggest deeper meanings, but here, his photos are more purely documentary, Garcia says.

“Later, Minor White goes on to make work that is more poetic and symbolic,” she said. “I don’t see that in these photos.”

Scholars sometimes discuss how White’s closeted queerness may have influenced his work. In notes for the show, Garcia mentions a 2015 article in Aperture by Kevin Moore, a photography historian, who argues that White’s photos of San Francisco—which more and more being seen as a gay mecca when he moved here in the ‘40s—were some of the “straightest” of his work.

White may have absorbed a certain hetero aesthetic from his mentors. Along with Adams, these included Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston. “Like them, White emphasized the formal disposition of elements within the frame and approached his subject matter with clear-eyed forthrightness,” Garcia writes. “On the other hand, the work of his mentors was ‘straight’ in the sense that it manifested their heterosexuality; masterful gazes at female bodies and natural objects were prevalent in their work. For White, the overlap of these meanings was untenable, and so he sought artistic inspiration in more veiled subject matter.”

Garcia says she finds it interesting how much of the city White crossed, giving us an on-the-ground view of San Francisco on little proof cards, showing people the daily life of the city—not photos of iconic views.

“He goes to the Fillmore and photographs the guy standing next to the stoop,” she said, referring to a memorable photo of Elks’ Shoe Shine Parlor on Geary Boulevard. “He doesn’t photograph the main intersection of the Fillmore.”

SAN FRANCISCO PHOTOGRAPHS BY MINOR WHITE Runs through January 22. Open Thursday through Saturday, noon-5:30 p.m. California Historical Society, 678 Mission, SF. For more information, go here.