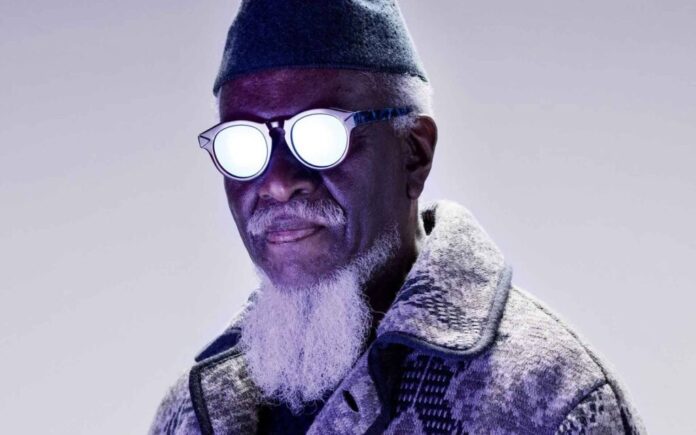

I was flattened upon learning that Pharoah Sanders passed away this weekend at the age of 81. It’s as if a very heavy door has closed on a certain era of transformative music.

Call it astral or spiritual jazz, out-there energy music, or blues for the cosmos—his music spoke to humans seeking something greater, a higher plane of consciousness.

When I first moved to San Francisco in the 1990s, I’d look for Pharoah Sander’s records in thrift stores, flea markets, and all the Black-owned record stores in the Western Addition and Lower Haight. Most of those shop owners would initially tease me. “You ain’t ready for Pharoah,” they’d say, before eventually locking the front door and going into the backroom or basement. They’d pull up a Pharoah album, with an Alice Coltrane record in tow, put them one by one on the record player, and wait to see if they got the right reaction. They’d sell them to me—after I passed their little initiation.

Sanders, born in 1940, was one of the last living legends who had a connection to players like Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, and John Coltrane. His easily-recognizable tenor saxophone playing earned him royalty status amongst free jazz players, critics, and collectors.

At the beginning of his career, Pharell Sanders was interested in urban blues music, until his high school teacher exposed him to jazz and took Sanders in an entirely new direction. Upon completing high school, he quickly packed his belongings, departing from Little Rock, Arkansas in 1959. He headed to Oakland, where he got a chance to play with saxophone players Sonny Simmons and Dewey Redman. We found out a couple of years ago that Bay Area jazz musician Joe Barrite, father of Marc Barrite a.k.a. Dave Aju, ran a notorious little jazz speakeasy in Oakland in the late ’50s and early ’60s that brought in a freshly-arrived Sanders. Soon after, Sanders met John Coltrane and moved to New York, where the major jazz scene was happening. He honed his craft at rehearsals with Sun Ra. But sadly, he was not making much money with the Arkestra, and soon found himself living on the streets. He tried to stay up all night playing, scrounging for money during the day, often selling his blood to eat.

It wasn’t until Sanders started playing with his old friend Coltrane that he would fully establish that “sheets of sound” fury in the world of free jazz. The Coltrane records on which Sanders featured laid the foundation for what was to come for both the worlds of free jazz and energy music. After Coltrane’s tragic death, Sanders would record further with his widow Alice, creating a gentler and more-structured aesthetic that became known as cosmic, spiritual, or astral jazz. During the last 30 years, Sanders wove elements of retro rhythm and blues, swing, and bop into his music—similar to what his contemporary Archie Shepp, another leading nonconformist of the mid-1960s, has done. Astral jazz, for the most part, was Sanders’ late-career calling card.

His impact can be heard today directly in the massive sound of Irreversible Entanglements and Jeff Parker, for starters. But Sanders’ legacy also lives on in the music he created over the course of 57-plus years. Here’s some entry points to this American master’s vast, genre-bending career.

PHAROAH SANDERS, TAUHID (IMPULSE! 1967)

Tauhid is the first of 11 albums that Sanders released on the Impulse! imprint over the course of six years. It stands tall due to the exquisite beauty of its opener, the 16-minute “Upper Egypt & Lower Egypt.”

PHAROAH SANDERS, KARMA (IMPULSE! 1969)

While Tauhid is widely regarded as Sanders’ best Impulse! album, Karma is his most well-known. The 33-minute track “The Creator Has a Master Plan,” featuring vocalist Leon Thomas, becomes a hypnotic mantra with its chanted iterations of the track’s title.

It’s elevation.

ALICE COLTRANE; PTAH, THE EL DAOUD (IMPULSE! 1970)

Sanders appears on the first of three Impulse! albums produced by harpist-pianist Coltrane (the other two are 1968’s A Monastic Trio and 1971’s Journey in Satchidananda.) Sanders plays tenor saxophone, alto flute, and bells on Ptah, The El Daoud alongside Joe Henderson, who handles a tenor saxophone and alto flute on the release.

Another astral jazz masterpiece.

PHAROAH SANDERS, BLACK UNITY (IMPULSE! 1972)

The title track takes up both sides of this record—and that’s still not long enough. As such, Black Unity is a cohesive, succinct, and powerful piece of art produced by Lee Young, Lester Young’s older brother. The trumpet was uncommon on most astral jazz albums of the time, but trumpeter Hannibal Marvin Peterson is a front-line partner here, along with tenor saxophonist Carlos Garnett. Producer Lee went on to work as an A&R executive at Motown.

PHAROAH SANDERS, LOVE WILL FIND A WAY (ARISTA 1977)

This was a brief detour in the direction of a more commercial sound, at the beckoning of then-head of Arista Clive Davis. The single “Love Will Find A Way” became a staple at many college and Black radio stations at the time. A bit “quiet storm” in style, but coming from Sanders, it still carried a deeper sentiment.

SONNY SHARROCK, ASK THE AGES (AXIOM 1991)

Ask the Ages was the final album released by jazz guitarist Sonny Sharrock—who performed with Sanders, bassist Charnett Moffett, and drummer Elvin Jones—before his death in 1994. Produced by Bill Laswell and Sharrock, it runs the full gamut from surging energy to quiet solitude. Rolling Stone wrote that it sounded like a “classic free-blowing jazz album from the Sixties had been recorded with the clarity and punch of today’s rock.”

It was the last time the free-jazz guitar pioneer Sharrock got to play with his friend Sanders.