A performance of choreographer Liz Lerman’s “Wicked Bodies” at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts begins in conversation with a witch. Gathered in small pods with a handful of fellow audience members, each artist of her multigenerational contemporary company, and local dancers who have been invited to join the core cast, tell of how much mysticism, myth, rigor, rage, beauty, and science can be held in one body, in one person. In one witch.

Lerman, an artist, writer, performer, and educator whose laurels include a MacArthur Genius Grant, United States Artists Ford Fellowship in Dance, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Award, and other honors, presents “Wicked Bodies” at YBCA Fri/28-Sun/30, simultaneously with the museum’s major new multidisciplinary exhibition, “Brett Cook & Liz Lerman: Reflection & Action.”

Together, the two presentations provide an intriguing blend of retrospective, present day assessment, and future-forward forecast of the choreographer’s vast body of work.

As creator of the Critical Response Process, a method for giving and receiving feedback, Lerman frequently conducts workshops and residencies on the technique. Central to her artistic practice are deep research, extensive engagement with the communities in which she is working, collaborations that defy categorization, and a commitment to cross-genre, diverse participants.

In light of that biographical enormity, it’s reasonable to expect that the origins of “Wicked Bodies” might be complex. They are not.

In fact, what lit Lerman’s spark was a slim-but-sharp sense of rage and indignation that she felt after viewing an art exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery in 2013. The show was entitled “Witches and Wicked Bodies” and, Lerman tells 48hills in a phone interview, its display of 500 years’ worth of prints and drawings of witches, unknown churchmen, and women artists were, “crude, pornographic, and disgusting.”

Nonetheless, she saw the exhibition as a demonstration of witches’ strength, power, conquest over diminishment—and even joy.

“I wasn’t interested in witches before I walked into that exhibit and saw those 500 years of drawings,” says Lerman. “[But] I’ve always been interested in women and women’s old bodies. I am old now, and I carried all of that with me that day. When I came out, I was emotionally wrought up. I felt this power from the women underneath it, even though they were being drawn mostly by men. I just thought, I should look into this.”

Looking into it began with a visit to the exhibition curator Deanna Petherbridge’s London home.

“There was a whole top floor filled with pictures of witches,” says Lerman. “As [Petherbridge] put it to me, she didn’t use some of them in the exhibit—they were so extreme. The museum told her they didn’t want her to use the word ‘misogyny.’ It set up for me that this is not just historical data, it has contemporary undercurrents. [Witches are] everywhere. It felt like a subject that could cross a lot of boundaries and borders: age, race, cultures, religions. Anyone joining me on this pursuit could come from any of those different directions.”

Soon, Lerman began talking to people—randomly, unrestrictedly—about witches. At a party, she struck up a conversation with a top-level executive who worked for Gor-Tex. “You know, that fabric stuff,” she says. “He was telling me how magical it is and how it’s being used in heart surgery. I asked if he thought of himself as a contemporary witch. He could have pulled back, but he leaned way into it.

“This is what I found out about witches: people have visceral reactions,” Lerman says. “One person I met, their family would take them once a year down the street to a lady who would brush them with leaves.”

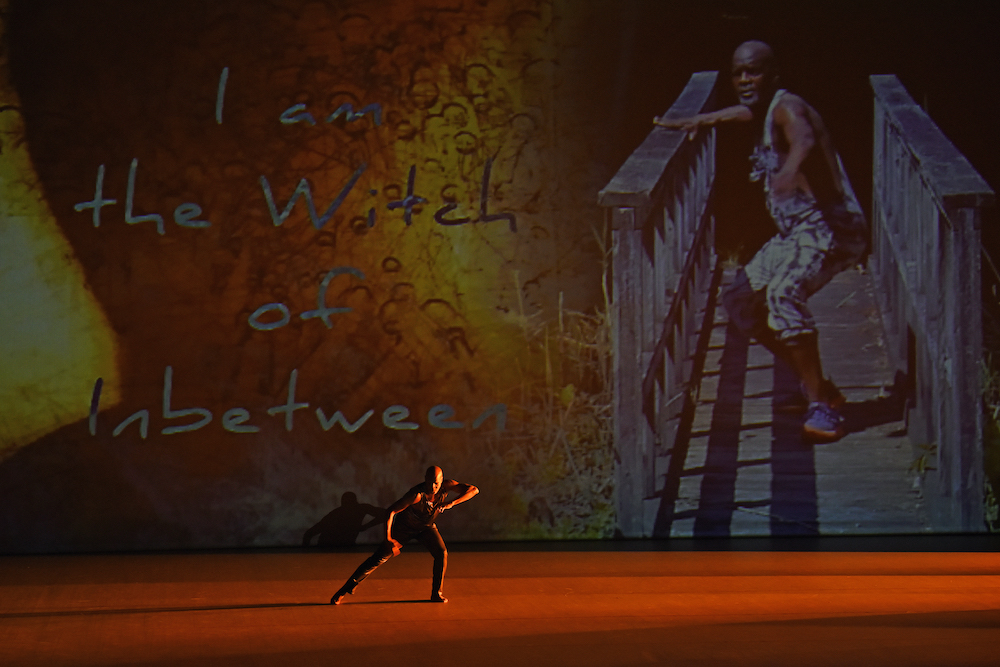

Negotiating the challenges of a body of information that is mystical, mythical, rigorous, enraging, and scientific at the same time proved to be fascinating. Writing spells that are basically the same as wishes, prayers, hopes, and dreams, Lerman and the cast of the resulting performance of “Wicked Bodies” conjured up various characters—including the Witch of In-Between, identified by her co-choreographer Keith Thompson.

“Even before ‘Wicked Bodies,’ he and I were getting close to things we’ve been working on,” says Lerman. “Keith is an African American with albinism, and there are parts of the world where he’d be considered to be a witch, and his life would be in danger. On the first day [of rehearsals] he said, ‘I’m the witch of in-between.’ That allowed us to get at things we’ve been working on for a long time in the making of his solo.” (Thompson was injured over the summer and this weekend at YBCA, his role will be performed by Vincent Thompson, who Lerman says is “marvelous.”)

“Feminine wisdom and histories are interesting to me, and aren’t relegated to people born in female bodies. One of the most interesting stories comes from Elisa (García-Radcliffe) who’s in transition. What Elisa told me about their real life transition made me ask if we could keep it present in the piece and they said yes. That’s true of all of the cast; each brought something they were deeply interested in to figure out.”

Lerman brought her investment in long relationships—or discovered it was a potent element in the creative process that stretched over the pandemic years and inevitably, led to life happening and unexpected changes. “The oldest person in the cast was my teacher, Martha Whitman, beloved by everybody,” she says. “She decided because of COVID and what was going on in her body, she couldn’t travel, so this was us coming up against the body, of not being able to count on your body. A decision was made to have her conjured by another dancer, Paloma McGregor, who had a long relationship with [Whitman]. So there’s something in this piece about the longevity of relationships. Keith Thompson and I have been working with each other for over a decade, Nia Love and I know each other because of family. It’s wonderful there are these relationships that held during this complicated time.”

Lerman says that the years of development behind “Wicked Bodies” was powered by the team “circling up” at the beginning of every rehearsal.

“Even if we were pressed for time, there’s that circle time,” she says. “It’s an unusual cast with different backgrounds. It took us a while to find ourselves and how we wanted to be with each other.”

Integrating local dancers with equally diverse backgrounds—flamenco, hip-hop, ballet—widens the wheelhouse. Each dancer learns group material, but also fashions individual solo material. Once you add on the fact that performers speak directly with audiences, and then dance for them, Lerman says, the production ends up “demanding a lot” of its artists.

“Wicked Bodies” when it bursts from pod to stage performance features the talents of many collaborators: Darron L. West, Sound Design; Sarita Fellows, Costume Design; Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew, Lighting Design: Olivia Sebesky, and the invaluable contributions of Thompson and the performers. About the local dancers, Lerman says, “I love the people I’m working with here. My early interest was in asking, how can the witches help people after the pandemic? What occurred to me was not a site-specific tour, but the idea of all of us—audience and performers—back in the theater together. It was intimacy, and then something like spectacle that’s way beyond our computers, pushing beyond videos.”

Everyday life and the bodies we inhabit or view in art are not rehearsals for the real things, which might arguably be the largest takeaway from experiencing Lerman insists that even dance rehearsals are not mere preparation: they are life, happening. That means that in every moment and every body, there must be value, discovery, commitment, invention, conflict, conversation, curiosity, questions.

“It makes for richness,” says Lerman. “You’re not putting off your life. Rehearsals try to teach you to be publicly perfect, over and over again. It’s a useless skill.”

LIZ LERMAN: WICKED BODIES Fri/28-Sun/30. Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, SF. More info and tickets here.