“What’s your favorite retro game, or one you’d consider a masterpiece? Is it a game you feel inclined to recommend to others?”

This question comes via email from Dan Salvato, the developer of Doki Doki Literature Club; we’re discussing his September 14 talk at Oakland’s Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment about retro game development.

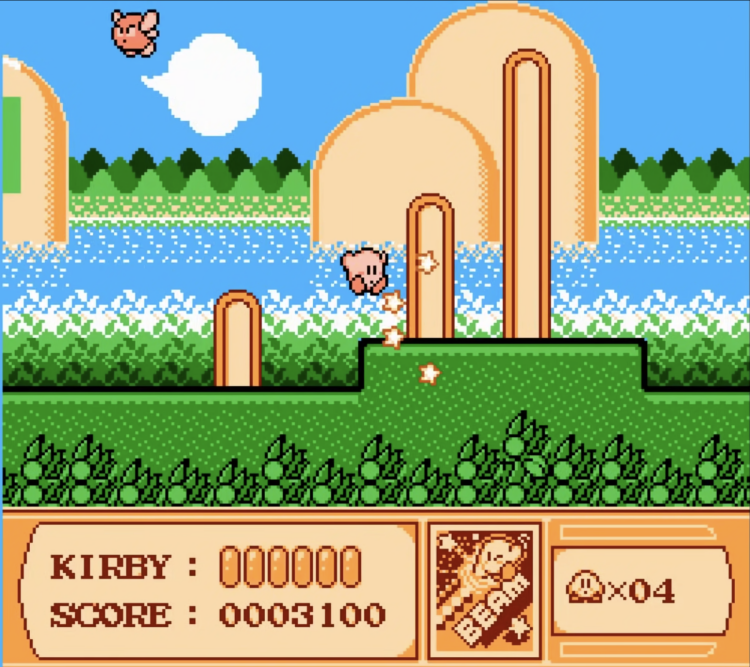

I’d asked him if he believes there are any lessons that modern developers can learn from retro games. His question in response immediately sends my mind in a few different directions. I think about Chrono Trigger’s delicately interlaced storytelling, Earthbound’s rich emotional textures, the surreal joy of Kirby’s Adventure. All of these games have given rise to development legacies that are still being carried on today: Last year’s hit RPG Sea of Stars wears its Chrono Trigger influence on its sleeve, while the whimsical tone and creative movement options in the recent platformer Penny’s Big Breakaway make it feel like Kirby’s younger cousin.

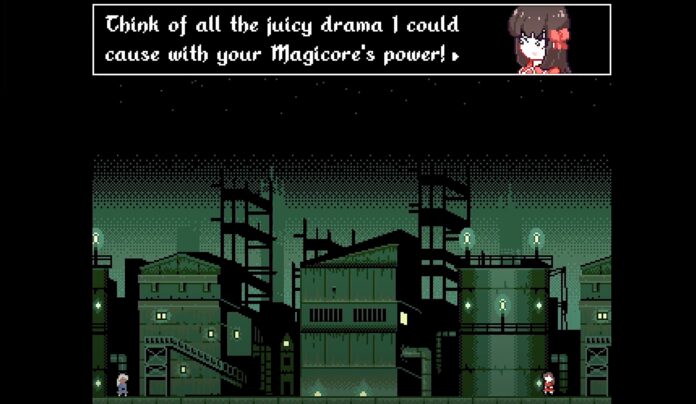

But Salvato is talking about taking that old-school inspiration one step further. Rather than developing retro-styled games for modern platforms, he’s discussing making modern games directly for retro consoles like the NES—or, in the case of his upcoming bullet-hell game Magicore Anomala, the Amiga.

It’s an intriguing idea. The games industry is one that has historically been characterized by constant technical progress, with each leap into a new generation implicitly rendering the previous one obsolete; Sony’s just-announced PS5 Pro represents the peak of contemporary console gaming, but odds are that it will seem outmoded in three years. In an industry that’s incessantly reaching for new benchmarks, what might developers gain from looking backwards?

For Salvato, developing for the Amiga has helped hone his programming and design skills. “In programming, everything is a trade-off: the most elegant code can be too inefficient,” he says. “I built an entire game engine from scratch that runs on bare-metal hardware. There was so much difficult decision-making in that process, so much rewriting code. But it’s really helped me develop these skills for deciding what trade-offs to make for a given set of problems. It’s a reminder that even developers back then had great systems that worked well, and the newest paradigms are not always strictly better for the problem you’re trying to solve.”

He notes that modern game design often doesn’t require this kind of intensive coding, as contemporary game engines generally have broader toolsets; this allows developers to spend less time trying to solve problems with code and more time actually building the game they envision. But these tools can also obscure what’s actually happening when we play a game: the computer illustrates images that we can interact with. “Today, there are layers and layers of abstraction between your code and the magic black box that draws your game to the screen,” he says. “But retro systems do exactly what you tell them to, and only that. It’s more intimate.”

This point was hammered home in the talk. Salvato formatted his presentation as a live coding demonstration, as he wrote, tested, and refined a simple Commodore 64 game over the course of about an hour and a half in front of the audience. This had the knock-on effect of demystifying what actually happens when a developer interacts with a computer. “Computers are very simple,” he said partway through the presentation. “The CPU takes numbers from the memory, does arithmetic on them, and puts them back in the memory… That’s pretty much all we’re doing, we’re just manipulating numbers, and then by magic, stuff happens on the screen. These old systems are so simple that we can actually understand those steps, which is part of the joy of this.”

The discussions of joy and intimacy—of magic—feel unique to retro systems. Over email, Salvato mentions that, while modern consoles are relatively homogenized, retro systems all have unique features and drawbacks, adding up to something that he likens to a personality. Watching him code in person, it struck me that what was happening was more or less a conversation between the programmer and the console; the trick was to learn how to talk to the machine in a way that it could understand, that accounted for the uniqueness of its particular language.

Ultimately, that’s what a video game—or any piece of art—is. It’s a conversation between the artist and the viewer that uses its particular medium to evoke particular feelings or ideas. As the mainstream gaming industry pushes toward consolidation and homogenization, the ideas that it’s willing to evoke become more limited. Salvato’s talk suggests that one path out of thematic limitation is, ironically, to embrace technological limitation. “It’s my opinion that the art of a video game goes beyond what the player sees and hears. There’s beauty in engineering, and I prefer to trust that consumers will notice when something is well-crafted,” he said over email. “I just want to make whatever I think is cool, and not worry so much about trends or industry stuff.”