This review of “New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century” (through January 30 at BAMPFA) is the result of conversations between three feminist writers—Wendy Trevino and Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta in conversation with Natalia Robyns-Kresich of 48 Hills—after viewing the exhibit.

“New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century” surveys contemporary feminist art by 76 artists working in photography, ceramics, painting, video, assemblage, and collage over the last 20 years. The exhibition, curated by Apsara DiQuinzio and Claire Frost, was originally conceived to coincide with the 2020 election, suggested by the neon “Vote Feminist” sign that hangs in the lobby. However, it was delayed by COVID for a year, and perhaps this is why this show seems slightly off-kilter in its contemporaneity. Much of it was curated with specific events in mind—such as the election of Donald Trump, and the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings—that have already receded into the near-background of public consciousness.

The 2000s is in some ways a difficult time period to survey, in which paradoxically, a lot has happened but also not much at all. An era begun by the disastrous invasion of Afghanistan—in which women’s liberation was used cynically as a pretext for war—ending in “our” recent exit, which neatly and dispiritingly bookends these past 20 years. It’s the post-9/11 period in which a generation of us grew up—the steadily worsening climate crisis, the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis, Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, the George Floyd uprising, #MeToo, and COVID— crises of our time, and corresponding popular responses.

We believe that art must reflect what is happening in the world and it must respond to—and take a position on—the conditions it exists within.

But a politically pluralist approach is always a tricky proposition, because some “feminisms” are by nature at great odds: For example, a feminism that includes trans women and men is not compatible with one that seeks to exclude them. A feminism that leads us into 20-year military occupation is at odds with a feminism that seeks to liberate us from imperialist wars. To put it another way, a multiplicity of these “feminisms” is not synonymous with a feminism that seeks the liberation of all women, and indeed, of all people.

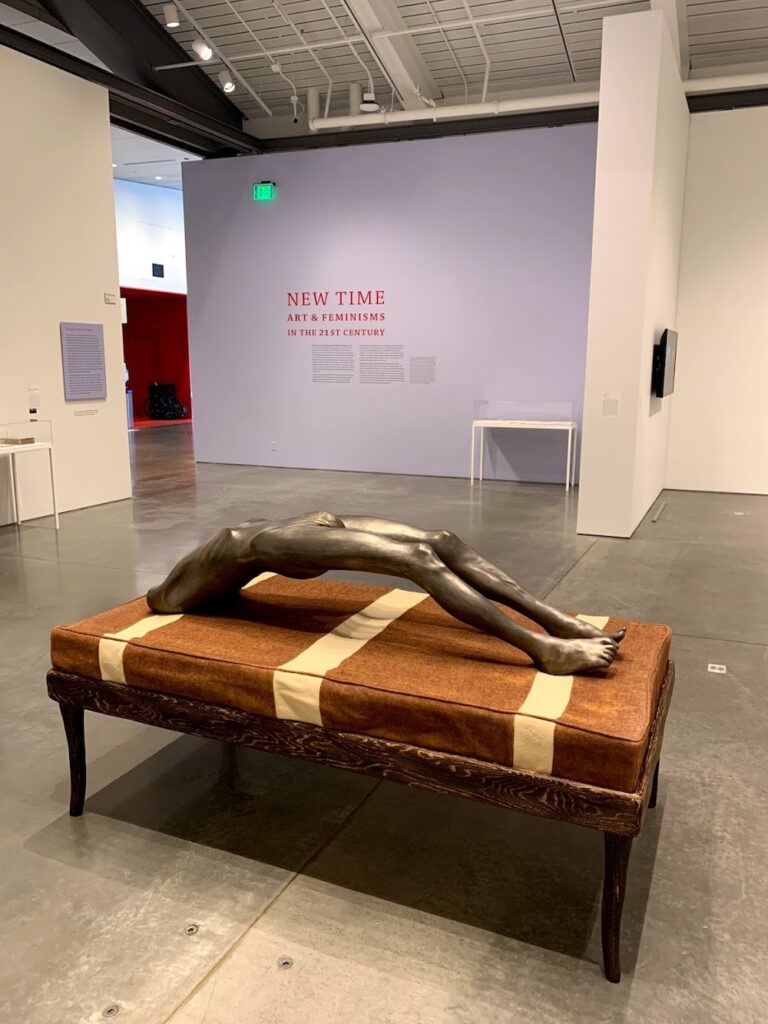

The exhibition, which takes up half of the museum’s gallery space, begins with a room called Prelude: Arch of Hysteria, that the curator defines as a kind of conceptual threshold through which one must pass to enter the rest of the exhibit. A framework. The room focuses on a concept that we might now refer to as medical sexism, specifically forced institutionalization—a period when women whose behavior was out of bounds or who became inconvenient to their families were “committed”. But it is also the gendered violence inherent to colonialism and slavery (that continues today in the form of Black maternal mortality rates or the forced separation of children at the border).

As with the rest of the exhibition, the art that deals with these themes directly, rather than theoretically, is the strongest.

Inka Enseenheigh’s surrealist painting In Bed captures the grotesque unreality of the medical confinement of women and other gendered subjects.

The exhibit gives us a rare chance to see Louise Bourgeois’ breastless, headless Arched Figure, on loan from the artist’s estate. This piece has never been shown in the United States, and this particular edition of the work has never been exhibited publicly. An androgynous figure in a state of near levitation from his/her hospital cot is a comment on the rapture and questioning that accompanies a diagnosis of hysteria. According to the assistant curator, Claire Fink, Bourgeois saw hysteria as a form of repressed pleasure not meriting of its medical treatment/punishment, but rather awaiting its own liberation.

Other well-known artists in the exhibit include Kara Walker, Kiki Smith, Jenny Holzer, and Judy Chicago—whose work is currently featured in a retrospective at the DeYoung.

Multiple works deal with the dissolution/abolition of gender in the 21st century. In Christina Quarles’ painting, Small Offerings, a pair of ambiguous and languid bodies recline in the heat of the noon-day sun. Much of Quarles’ work features pairs, that, whether stationary or in motion, seem to be in the process of transforming into one another. Quarles writes of her paintings, “I see my work as exploring the ambiguity of identity. My figures I see as moving between genders.”

Likewise, South African artist Zanele Muholi’s portraits from her series Brave Beauties reminds us that the beauty is that her subjects simply exist, no matter what their gender categories may be.

Also notable is the photography of the late lesbian Chicana artist Laura Aguilar, whose self-portraits convey a spiritual largess to the viewer. Her naked body is so grounded and integrated into its surrounding desert landscape that the portraits are reminiscent of land art.

Lava Thomas’ exquisite black-and-white portraits of Montgomery Bus Boycott participants Jimmie L. Lowe and Mentha L. Johnson pay homage to lesser-known participants in the Civil Rights movement. The portraits are based on mugshots taken in the month of February 1956, in which 80 people, most of them women, were arrested. (For context, the Montgomery Bus Boycott was sustained by working women, mostly maids and cooks. A secondary circle of women cooked meals to distribute to participants and supporters, financially sustaining the boycott and elevating mere “women’s work” into something completely essential to a larger movement.)

Kalup Linzy’s All My Chillun and Tammy Rae Carland in Becoming: Billie + Katie 1964 bring unexpected humor to the exhibit through their respective reproduction of daytime melodramas and portraits of the artist’s parents. Linzy returns to the daytime soap operas of his childhood and inserts himself and his family into them by playing all the roles. Carland recreates the family photographs that her parents lost in a fire, playing both her mother and father in different stages of their family life.

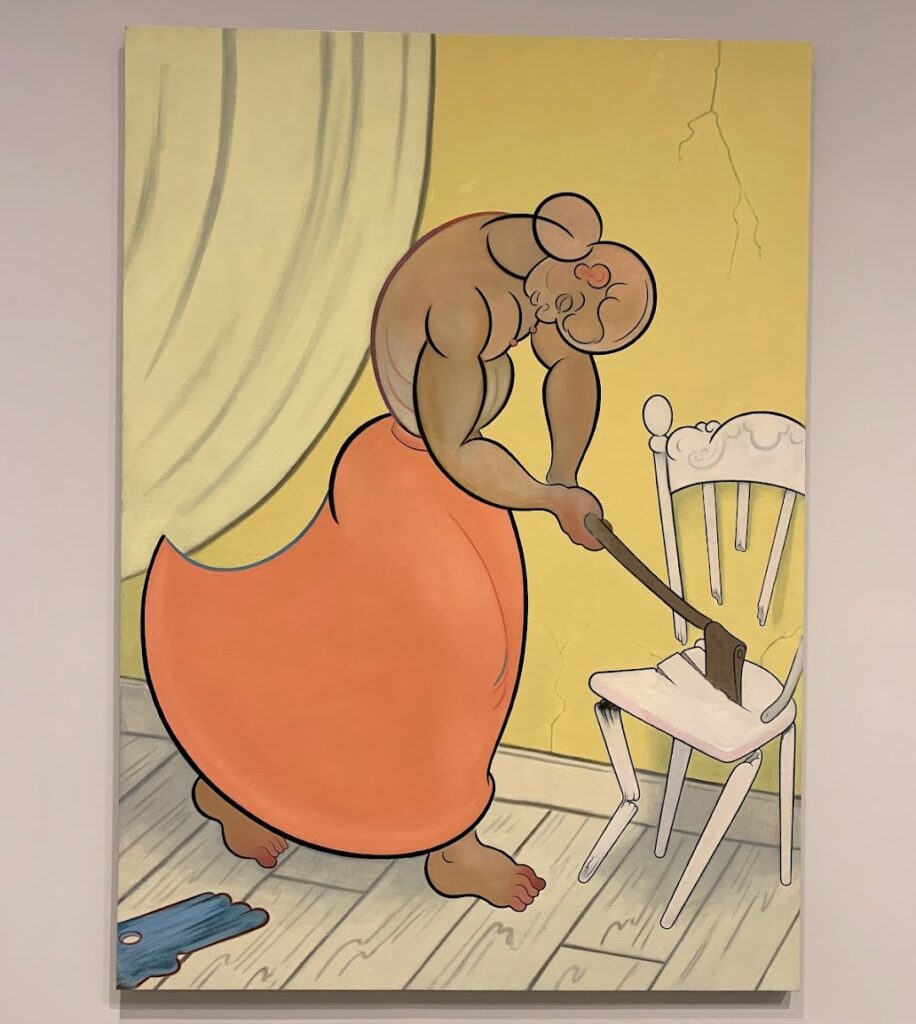

Koak’s Breaking the Prairie would have been an excellent featured image for the exhibit for its direct visual impact. The image of a woman breaking a chair with an axe, and thus striking against domesticity—has a symbolism and power that is immediately understood. Its immediacy allows for a subtext within the painting, the destruction of this continent’s ancient prairies and forests.

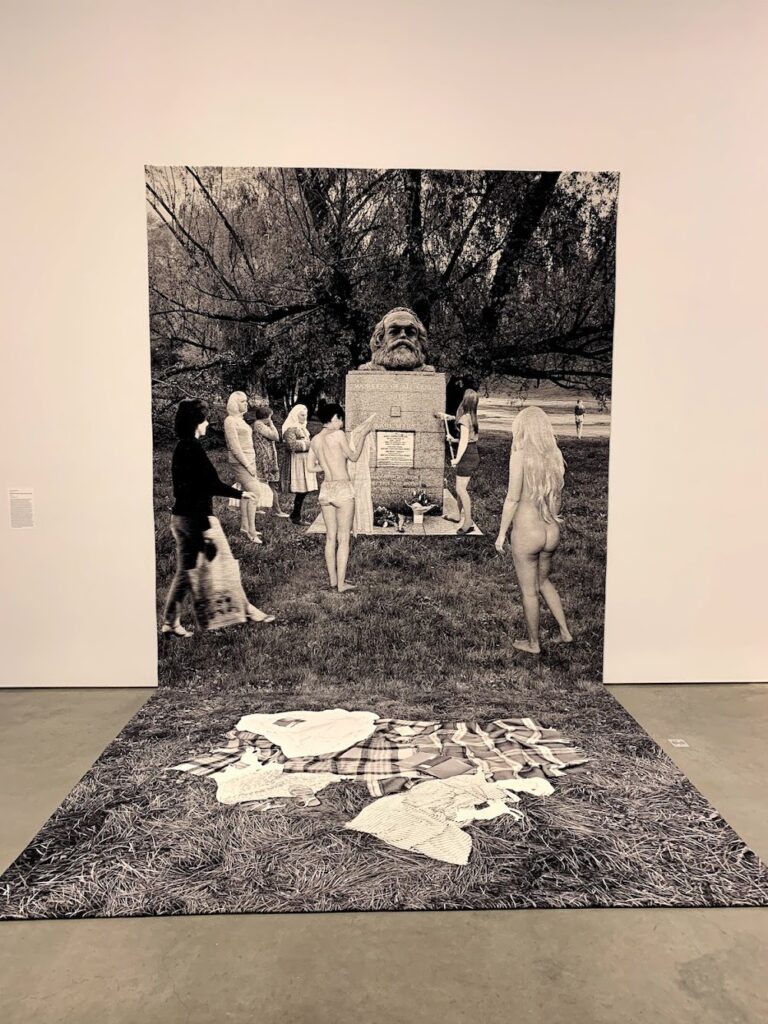

One piece that felt out of touch in 2021 was Goshka Macuga’s Death of Marxism, Women of All Lands Unite, a collage of imaginary women picnicking on Marx’s grave. Macuga’s subjects are taken from the photographs of the Czech artist Miroslav Tichy. Tichy’s voyeuristic photos of unsuspecting women were taken without their consent, and Macuga duplicates that intrusion when she reassembles them into a work of highly ideological historical revisionism. We don’t know how any of the women in these original photographs would feel about being utilized in this way. The artist sets women as a category in opposition to Marx without considering what actual relationship to Marxism they may have. Indeed, many feminists continue to use and draw inspiration from the Marxist framework today.

In reality the full story is that to the immediate left of Marx’s grave, but not depicted in Mucaga’s piece, is the grave of Claudia Jones, a Trinidadad and Tobago-born Black feminist who asked to be buried next to Karl Marx in the Highgate Cemetery of London. That information, of course, is not contained in this piece—and if it was, the imagined women would be stepping on her grave as well. Jones was a Marxist who campaigned for equal pay, paid childcare, and public education for women.

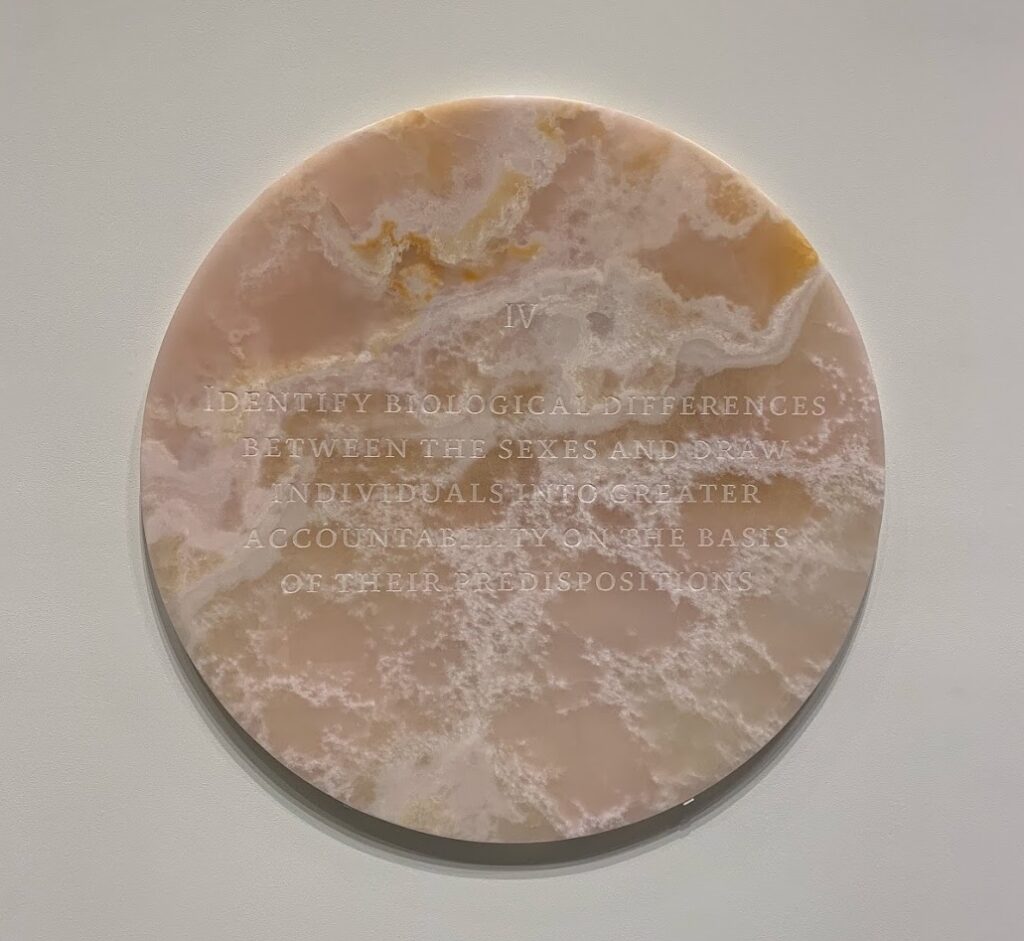

Another work that seemed to go awry of the exhibit’s objective of plurality is 13 Tenets of Future Feminism, a collaboration by several artists of feminist aphorisms engraved into outsized rose onyx disks, a weirdly oblivious choice of materials given the environmental destruction inherent to our present extractive economy. We hope a ‘future feminism’ will exhibit a greater awareness of our current realities and will involve keeping precious minerals in the earth.

But in fact, feminism doesn’t need its own stone 10 commandments, or Articles of Faith… it is a movement that needs to be revisited and reevaluated by every new generation. Otherwise, we risk memorializing outmoded ways of thinking, like biological essentialism. If anything is to be literally set in stone it should at least be one of the perennial demands for an improved material reality for women—for example, “Free Abortion without Apology”—or another equally urgent mandate.

One of the best pieces in the exhibition comes towards the end: Chitra Ganesh’s Sultana’s Dream, a series of 27 linocut block prints that are portals into a future world of restored ecology, women’s discovery, recreation, friendship, and a home life free from the responsibilities of the domestic and social reproduction necessitated by capitalism. What a relief! Every print is a window into a future that we have all dreamed of at one time or another. The viewer connects to the rudimentary physicality of the medium, where within the grain of wood is a world of analog detail. The block print has immediate and mass appeal as a people’s medium, out of which much art to inform movements has been made.

Feminism as a theory, as art, and as strategy, will always have limitations—but it will also always have possibilities, and it is the limitations that provoke the search for possibilities.

“NEW TIME: ART AND FEMINISMS IN THE 21ST CENTURY” runs through January 30 at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archives. More info here.