There was something serendipitous in attending this press preview two days after the infamous Oscar “slap seen ‘round the world.” Much as already be written about the fact that it included two Black men in front of a primarily white audience. After three decades as Hollywood’s most jovial negro, Will Smith is now ostracized by the very people who bestowed upon him their highest award. In a way, Hollywood suddenly remembered that Will Smith was Black. Roman Polanski still has his awards, though.

That gray area of acceptance and risk is one of the many Black identity minefields in the Museum of the African Diaspora’s new Spring-Summer lineup. It’s been two years since the MoAD closed its doors to COVID, delaying the appearance of several of the very installations now showcased. After slowly re-opening last October, the Museum’s proper return finds itself in a world where Black voices are still overwhelmingly ignored.

After the OK vaccine check at the door (no QR codes are scanned), the first installation welcomes the patron so subtly that one would be forgiven for missing it. Sam Vernon’s “Impasse of Desires” (2020, curated by Elena Gross, running through Sept. 18) is, according to Vernon herself, “a direct response to and activation of MoAD’s first floor gallery space and hallway.” It hangs above the MoAD lobby as a collection of near-invisible mosaics on sheer textiles that wave like UN flags. The images on the tapestries primarily show Black figures against cut-out backdrops (though one is a rose against a chainlink fence, recalling the 2Pac poem “The Rose that Grew from Concrete”).

Indeed, the textiles provide a fine addition to the otherwise sterile MoAD lobby, but their effect can be as transparent as the images themselves. Inspired by the Matt Richardson book The Queer Limit of Black Memory, Vernon’s installation works better as decoration than bold statement, lacking the punch of the collages and drawings seen on her own website.

Heading up to the second floor salon puts one among another thread-based installation. “The Threads that Bind” (also curated by Gross, through June 12), is—as stated by artist-professor Cynthia Aurora Branvall—the result of being raised in “a family of professional sewers.” A few tapestries (Continents, 2014-16) feature finely-knit antebellum-era collars stretched to imperfect lines across the canvas. Other works feature “19th Century blouse[s treated in] beeswax, damar, [and] resin” to hold their shape as if they were actively being worn.”

Similarly, Little Girls, Birmingham (2020-21) features affecting resinated collars that stand in for the girls killed in the terrorist bombing at 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963. The titular piece (The Threads that Bind a Nation, 2020) recalls the first, with fabrics shaped into the United Stated, divided in half from the traditional “north” and “south.”

Even without reading Branvall’s accompanying text, her pieces are striking. The threads are cotton, intricately embroidered by hand, worn by women whose likenesses one can almost make out if one stares as the sculptures long enough. The tales they tell are often missing in a United States as divided as the titular piece illustrates. As Branvall herself said during the preview I attended, Black artists “are filling the gaps” left by the vacuum of those missing stories.

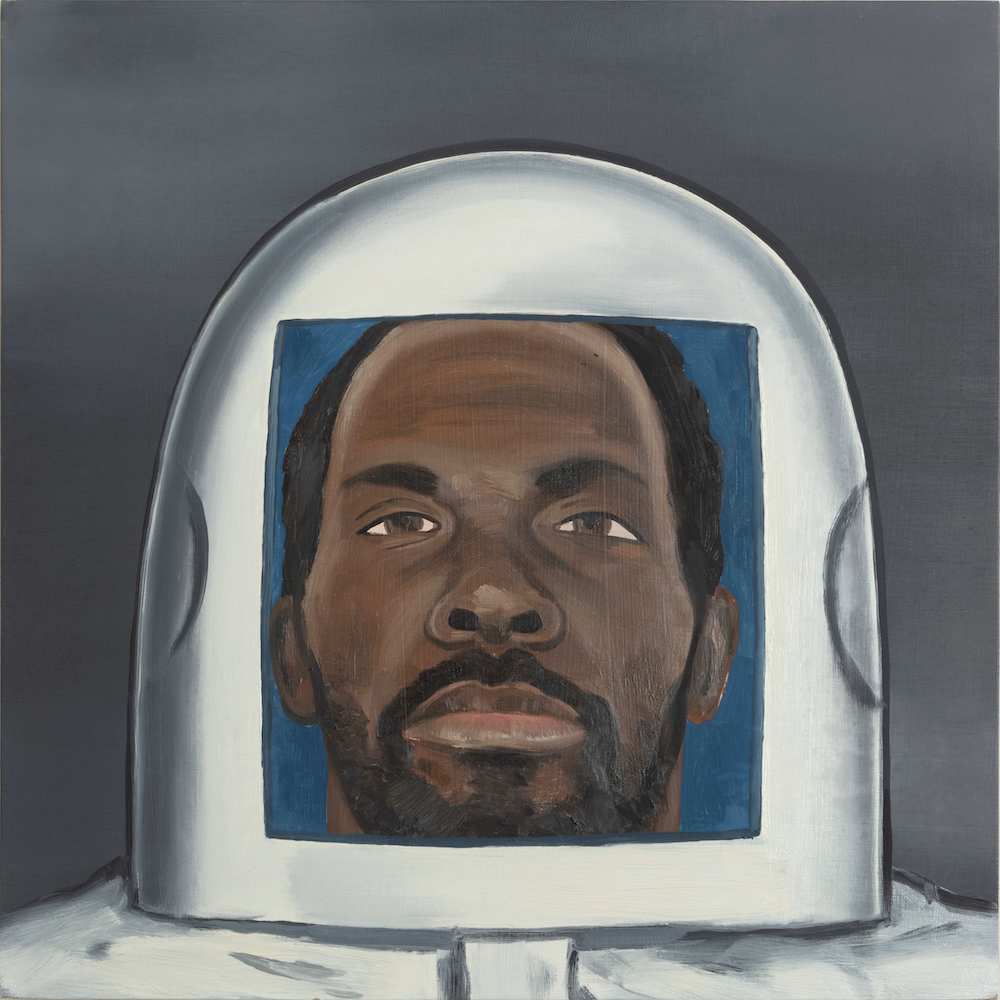

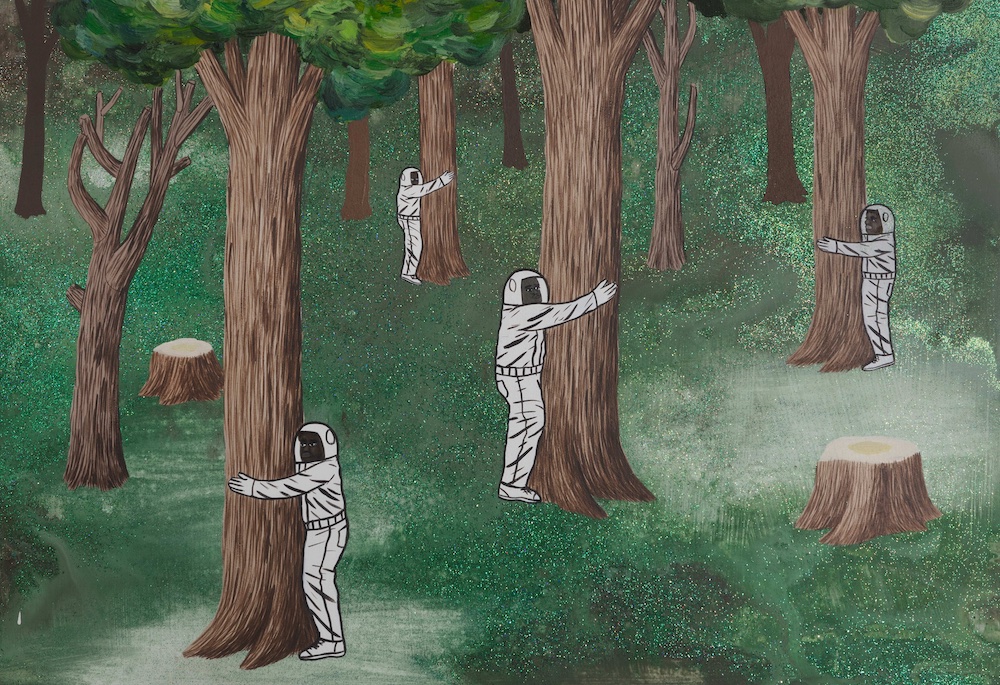

In the gallery section, one walks among the work of the Bay Area’s own David Huffman in “Terra Incognita” (co-curated by Gross and Emily Kuhlmann, through September 18). Huffman self-describes as “one of the first Afro-futurist artists,” and his “Traumanauts” act as extraterrestrial visitors in their own homeland. This includes a short film (Traumanaut Tree Hugger, 2011) in which the title character makes good by wrapping his arms around various redwoods as Lynchian music and droning sounds play (though there were some sound issues during the preview). The character does so in a spacesuit that is on display in the gallery, one Huffman says NASA created at his request.

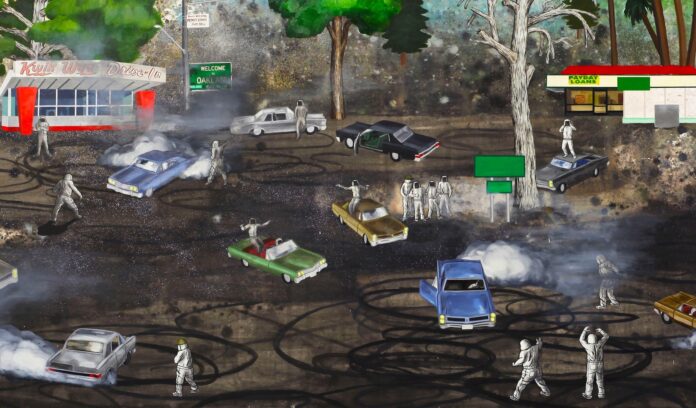

The other pieces (and there are a lot) use Huffman’s simplified drawing style for an appropriate funhouse mirror view of race and rural American. The wall-sized triptych Katrina, Katrina, Girl You’re On My Mind (2006) has the Traumanauts atop various New Orleans homes and businesses flooded by hurricane waters that appears as an all-encompassing gray void. Sideshow transports them to Oakland, where the gray is the smoke coming from skid marks made by one of The Town’s most infamous past times. Placed around the gallery are Huffman’s Gigantor-esque sculptures with golliwog-esque faces.

It all makes for an engaging spectacle by an Oakland-based Black artist who not only remembers the height of the Civil Rights Movement, but absorbed as much pop culture ephemera as his white peers—ephemera that rarely featured Black faces. During the preview I attended, Huffman openly lamented that “Black artists haven’t been allowed nuance” in the mainstream. It makes sense that his work looks to cover as many bases as possible with the materials he has at hand. Political stance doesn’t disappear with entertainment, the two are symbiotic.

The third floor leads us through “Elegies: Still Lifes in Contemporary Art.” Curated by Monique Long (through August 21), it’s “a group exhibition bringing together an international group of artists who have disrupted or extended the traditional presentation of still lifes.” Standouts include Rashaad Newsome’s The Art of Immortality (2019), a collage of diamond jewelry resembling a vase of flowers, Black mouths in place of the pollen, boasts a materialism message that’s mirrored in Sadie Barnette’s Birthday Flowers (2020), featuring Swarovski crystals used as dew or sparkles on a photo of wilting pink roses.

Yet the photos and paintings along the walls must leave plenty of room for Devan Shimoyama’s For Tamir VII and VIII (both 2019). Each consist of metal swings adorned in flowers (one accentuated with diamonds, the other with angel wings), a haunting reminder of the childhood taken away because someone refused to look at a Black child with the nuance Huffman mentioned.

I found myself pondering the “nuance” statement after my first MoAD visit in years. It’s never had the patron numbers of SF’s other “Mo” house, but it’s to the MoAD’s credit that the works were worth the two-year wait; it’s to the world’s shame the problems featured have, in Cynthia Branvall’s words that day, only gotten worse since. Its necessity is more apparent than ever.

The various exhibitions run through numerous dates (listed above) at the Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco. Tickets and information here.