This is Good Taste, your weekly look at food matters in the Bay Area. In this edition, you’ll get a peek into the progress of the latest iteration of Cafe Ohlone, a collaboration with mak-’amham and UC Berkeley’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology called ‘ottoy.

I witnessed history (and fought back tears) this past weekend as mak-’amham’s founders and partners Vincent Medina and Louis Trevino offered the general public a preview of ‘ottoy, a new presentation of Cafe Ohlone in partnership with Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology that’s currently under construction and slated to open in June.

Founded in 1868, the university and museum sit on Ohlone land, caused the tribe to lose federal recognition in 1927, removed buried ancestors, and still have not released all the remains, though that process has begun. Nearly 100 years later, this collaboration crystallizes a healing process.

“It’s a page-turning to be able to see an Ohlone visibility throughout this space,” Medina said, looking around the museum’s courtyard at the newly-planted native trees, medicinal plants, shellmound, and dry creek, along with custom-made redwood seats and tables. “We can’t stress enough how important this is and how big of a moment this is for our community.

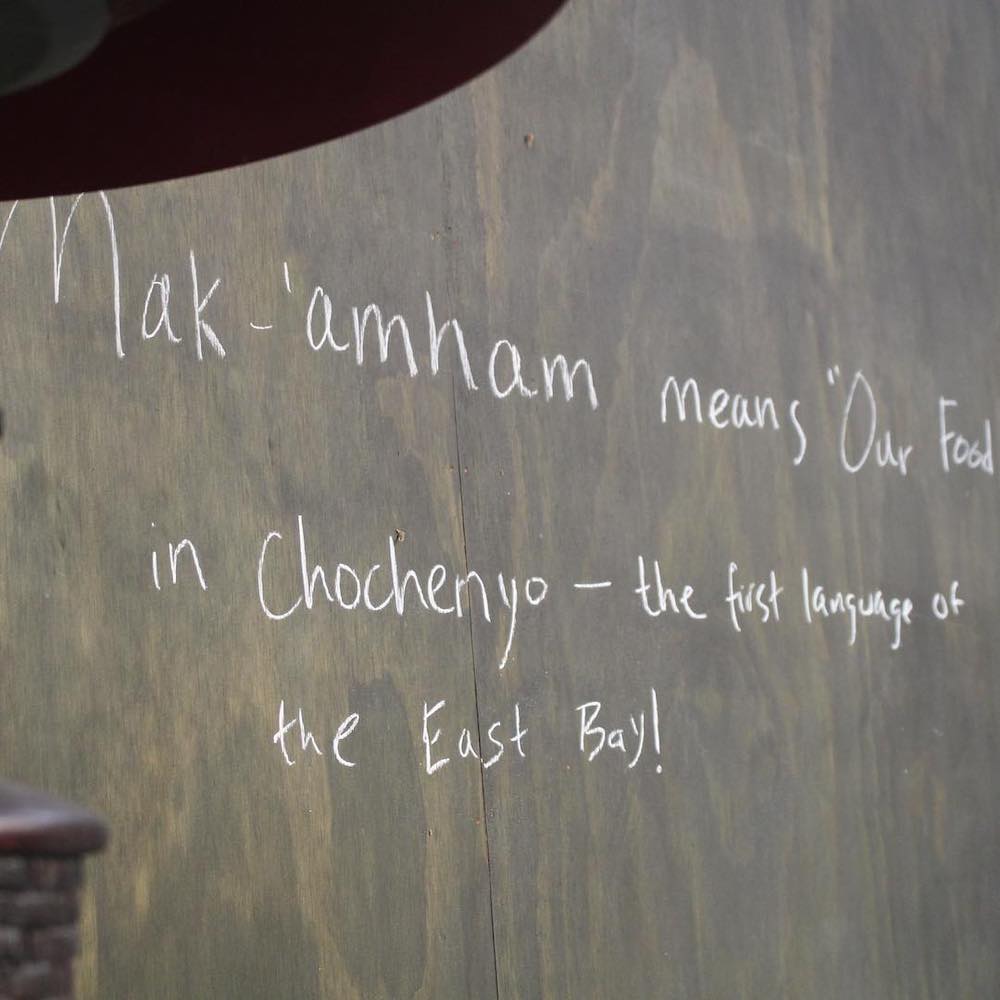

“Beyond Cafe Ohlone, we are also naming [the project] ‘ottoy, which means ‘to mend’ or ‘repair’ in Chochenyo language,” Medina continued. “Chochenyo is the first language of the East Bay, the language that’s always been spoken by our family, still spoken by our family today. An ‘ottoy — to repair — is something that is weighing very heavy in our hearts. To see repair happen between these relations, relations that have long been difficult and painful for our Ohlone community. When we think about the history here at UC Berkeley, about the damage that’s happened for 150-plus years. How the university had a direct hand in the loss of our tribe’s federal recognition and removed our ancestors from their cemeteries. And while we acknowledge that things are not fully fixed yet, being able to be here in this space will be a constant reminder that the Ohlone people are alive, our community is here, that we’ve never left our home, and we never will.”

When doors open in June, visitors will have a number of options to enjoy the space: tawwa-sii Wednesday, a weekly tea hour with small bites; a Thursday lunch tasting, weekly dinners called mur; and sunwii Sunday, a multicourse brunch service served “one dish after another in a high-energy, bold manner,” according to the website.

Thanks to a cleverly concealed sound system provided by Meyer Sound, the trees will sing to people as they enter the space. The soundtrack includes specially recorded voices of both elders and youth in their community as well as a new Chochenyo version of Rosie and the Originals’ “Angel Baby,” a favorite English song of the elders from the Sixties. The trees will also be known to occasionally gossip with each other.

“Beyond this being a restaurant, this is going to be an educational cultural hub to be able to teach of how living our culture is so that people get to learn firsthand from our voices who we are as the first people in a way that is not adversarial, but in a way that brings people together,” Medina explained. “To be able to show the value of when Ohlone culture is central in our home, everybody wins. We win because we see visibility; we give a reminder of our presence. We get to heal old wounds with our unity and the public wins because we get to teach another way of being about how we, as the first people here, have value. About how we, as the first people here, are able to teach about the original values, the original value of this place, and for those things to trickle outside of Cafe Ohlone into the world around us.

“We’ve seen this happen already, through Chochenyo language spreading throughout campus, through letting the public know that Ohlone people are here and those misconceptions that have lingered for far too long, how easily those are to shatter when we can share our story directly. To be able to know that this place has never been a new world, but that this place is old, has an original identity.

“When we can share these foods together, be able to eat together, be able to share a story together, share games together, be able to talk about how long we’ve been here and also those hopes that we have for the future, we all win together,” Medina said. “This is a collective thing.”

Find more forward-thinking food stories at Tamara’s site California Eating.