Supervisor Rafael Mandelman has been trying hard to get houseless people off the streets. But judging by his new bill, his definition of getting people off the streets does not mean getting them into housing.

For the second time in two years, he is proposing legislation to the Board of Supervisors, where it will be heard first at the Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee Thursday/12. If it passes, it would put people into temporary shelter: a tent in a sanctioned camp, a cot on the floor or, if they’re lucky, a “tiny house.”

On March 22, Mandleman introduced his “Place for All” legislation. This is version 2.0 of the “tents for all” legislation he had tried in 2020, but did not get enough votes for. After making some changes, he decided to give it another spin.

This time, rather than only providing folks with safe sleep options such as sanctioned, monitored outdoor encampments, the offers were broadened to include other forms of shelter, including some with bathrooms. However, it is essentially the same concept: people are forbidden to sleep outside even though there is no permanent housing available to them. Instead, everyone who sleeps outside will be offered a shelter spot who wants one.

Of the people who accept, only 20 percent of them will be assigned safe sleep sites. Also, only half of the sites would require bathrooms (since this was the sticking point on the first version). Offers may include safe sleep, tiny homes, shelters, hotels or non-congregate shelters — but they do not include actual housing.

Here’s how Mandelman aims to make this happen: Within three months of the legislation’s passage, the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing will do an assessment of the need among unsheltered residents. There is no detail as to how this will be undertaken, but overall “need” is defined as the number of people who would take a shelter bed if offered to them. The latest figures from the most recent homeless point-in-time count in 2019 showed that 5,000 people were living unsheltered in San Francisco so whatever number that the department produces will be lower. The department has also claimed in some cases that 30 percent “reject services” so we may expect some similar pronouncement to inform this. The department would be given 36 months to develop an implementation plan and a budget of the costs of providing beds, which would be up for approval at the Board of Supervisors.

While appearing to address the critical problem of homelessness, this legislation will in fact be both ineffective and cause further harm. Here’s why:

- The proposal includes no funding sources. Yet, the cost could run up to $400 million per year based on the number of unsheltered people and the cost of a bed at shelter sites. We have a very limited pot of money for housing and homelessness in San Francisco, a vast majority of which is from Proposition C. The measure’s emphasis is on permanent solutions and for a very good reason: that is where the evidence points to as the most effective long-term solution to the problem. Mandelman’s shelter legislation would create serious competition for the funds that are meant for permanent, supportive housing. This shift would mean more people are served by temporary non-solutions that only kick the can down the road and fewer people would get access to the actual stable housing solutions needed to stay out of homelessness. Essentially, the very people this purports to help will suffer as their options become even more limited by a raid on the housing funds meant for them.

- Prioritizing shelter is not helpful if there is no housing for folks to move into. Shelter beds will fill up and new people will not have access to them. The idea that shelters are a place to wait while housing is built is not well thought out because shelters are neither cheaper nor faster to put in place. Housing subsidies in the private market, for example, can be put in place immediately without the need to bring in showers and bathrooms.

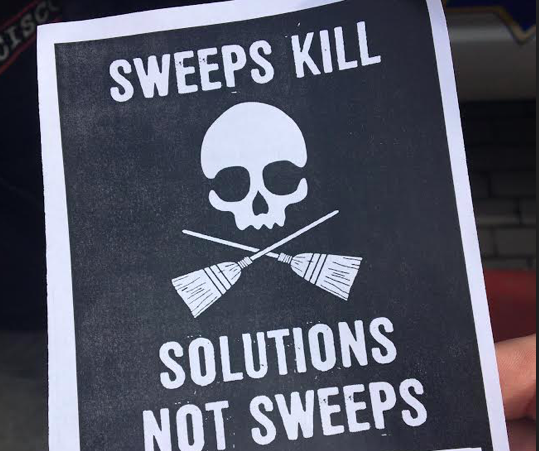

- Sweeps of homeless people already occur daily without an offer of shelter in SF. Another way this will hurt the very people it claims to help is through increased sweeps of encampments and forced evictions of people living on the sidewalk. Because of the Martin v. Boise decision, it is illegal for cities to ban people from living on sidewalks if they are not first offered housing. Under this legislation, the city would be provided a viable claim of offering a shelter option to everyone, therefore justifying the forcible clearance from their makeshift shelters. Mandelman himself has not been shy to admit this. This is clearly not just a bug in the legislation, but a feature.

Aside from the harm that could be done by this ordinance, there are also questions of how realistic or achievable any of this proposal really is. This is why it is not hard to question whether it is all simply a stunt to demonstrate an aggressive approach in order to satisfy constituents or potential voters:

- Even if we go with Mandelman’s likely lowballed estimates of the need for beds which he has put at between 1,000 to 2,000 (with no explanation of how he got there), and a cost of $80 million to $160 million, it seems quite impossible that we would create this many beds for homeless people within 36 months. Assuming full funding, the city has never had an easy time finding sites for shelters, supportive housing or other homeless programs. Where would the locations be for these beds? In most neighborhoods, “not in my backyard” opposition is strong. Landlords want top dollar for their properties and the city very prudently wants to avoid overpaying for real estate. Vacant buildings suitable for shelters in areas where residents can access public transportation and services are few and far between.

- Finally, once spaces are found, who would run the shelters? Service providers are in short supply, and they face serious staffing shortages, as well as challenges with high turnover, recruitment and retention. It’s not a simple task to add thousands of new beds very quickly and contract qualified and experienced organizations to run them.

A housing component would be critical if this proposal actually had one. If successful, this legislation could quickly move 1,000 to 5,000 people into shelters. Eventually, every one of these people will need permanent housing or they will be back on the streets, and we will be back to exactly where we started, only with fewer resources to solve homelessness.

However, San Francisco has an affordable housing shortage. While these thousands of shelter beds are being created, an equal number of permanent supportive housing units won’t be magically created. As mentioned before, expansion of permanent supportive housing may in fact be seriously hampered during this time, since most resources will be diverted to enacting the legislation.

Unless this experiment is intended to be a decades-long (or even permanent) warehousing of people who need homes, there needs to be appropriate numbers of housing units available for them to exit into. We can catch a glimpse of what this might look like by examining the city’s shelter-in-place (SIP) hotel program. About 2,000 were temporarily housed in SIP hotels throughout the pandemic. Yet, as hotels closed, nearly 1,000 of them had not been given units to move to permanently. The city had two years to move people into permanent supportive housing units and they were only able to house about half of them. They consistently fell well below their own goal of housing 157 per month (based on having everyone housed before closure), often being closer to 50 or 60. At this point when the last hotel is closed, 500 people will still be unplaced. These were the results when these residents were prioritized above all other unhoused people in need of housing. Imagine also competing with those on the streets, the pace would be that much slower. It is hard to believe we will have enough units, and it is hard to have any real faith in the Homelessness Department bureaucracy to ensure that thousands of people aren’t stranded in shelters forever. How will this be any different?

Sara Shortt is director of public policy and community organizing at HomeRise, a San Francisco-based housing nonprofit organization.