Sups. Aaron Peskin and Connie Chan want to make public the names of landlords who are keeping neighborhood storefront property off the market.

It’s a concept that could also in the future be applied to the Vacant Homes Tax, which may be on the November ballot.

They introduced the legislation May 10, and it will be heard in committee next month.

The reason this is important: Landlords of all stripes like to keep their tax data secret, but transparency could be a huge incentive to quit hoarding property, waiting for rents to rise.

But there’s more to this story.

In essence, the legislation could create the equivalent of a rent-registration operation for commercial (and potentially later, residential) property—and allow the city to help small businesses navigate the world of commercial leases.

“It could be very exciting,” Lee Hepner, an aide to Peskin who helped write the legislation, told me. “It could put the city into the role of commercial vacancy broker and provide the links between small businesses and brick-and-mortar spaces.”

The legislation would, among other things, shed some light on the world of real-estate brokers and permit expediters. It would allow any small business owner, or potential business, to see what properties have been empty for how long, and how much tax the owners are paying to the city—which might make it easier to negotiate a lease.

There’s also a political element: “The duration of a vacancy speaks to whether a property owner wants to be a productive member of the community,” Hepner said.

This bill is all about commercial vacancies. But imagine if the same principle, and similar legislation, were applied to the Vacant Homes Tax, which I suspect is going to pass in the fall.

If tenants, activists, and journalists can find out which apartments have been held off the market, and who their owners are, it could have profound implications for planning policy.

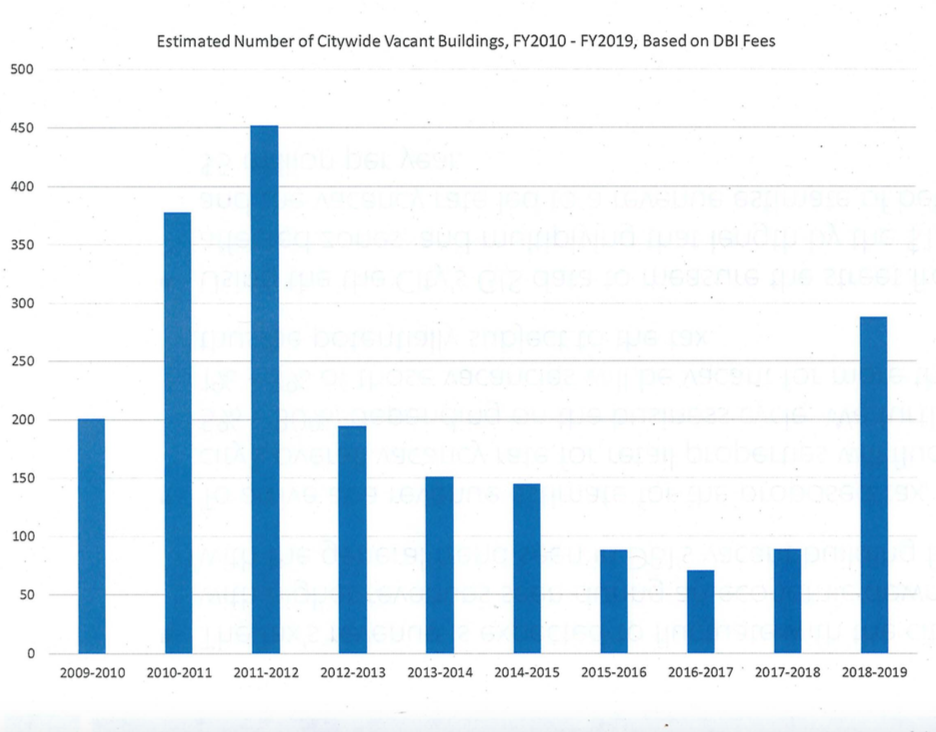

For years, the city has promoted high-rise market-rate condos, mostly in Soma, as a solution to the housing crisis. But what little data we have been able to gather suggests that a lot of them are empty a lot of the time. We also know that there are about 40,000 other vacant units in the city—enough, if you believe in markets, to have a greater impact on rents than all of the development the Yimbys are pushing.

But nobody knows exactly where they all are, or who owns them.

A little sunshine on that could be transformative.

If developers are building condos for people who seem them as investments, not as housing, maybe that’s not a solution to the crisis.

If landlords are holding usable housing off the market—maybe waiting for rents to rise even more—that might suggest that the city should be buying those units, or financing nonprofits buying those units, and renting them out—which might be cheaper than building new affordable housing.

I don’t think anyone else in the news media, or in the political world in general, is paying much attention to this bill. But it could be a very big deal.