If anyone somehow managed to miss or avoid the pandemic’s greatest lessons—that life is wildly unpredictable; human mortality is the only definite, but its timing is elusive—South African artist William Kentridge is here to remind us. Among the highlights of his recent University of California, Berkeley and Cal Performance six-month residency that included films, lectures, a solo performance by Kentridge, and more was the US premiere March 17 through 19 of his multi-disciplinary “SIBYL” at Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall.

The two-part work was comprised of “The Moment Has Gone,” a 22-minute film with a score composed by Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd, and “Waiting for the Sybil,” a 42-minute chamber opera commissioned by Teatro Dell’Opera di Roma in Italy, where it had its premiere in 2019.

Begun two years prior to the pandemic, the work’s remarkable primary themes include the all-consuming thoughts and truths we faced during the last three years. Here we find fate, death, algorithmic dependency, erasure, fragility, clinging to anything for solidity while incessantly spinning to the point of dizziness, and staggering with each passing wind or word or rumor or other elemental force. Collectively, it is an astonishingly visual and aural piece of theater performed the film by Kentridge, who we see working in his art studio, along with his counter egos: the animated Soho Eckstein character (found in a series of Kentridge’s films) and, with an effective wry twist, by a second Kentridge who critiques and chides his double. Featuring Kentridge’s brashly expressive drawings in ink and charcoal and accompanied by four singers in coveralls, we watch art in the moment of creating. Images are made and erased, redrawn and over-drawn, painted, splattered, and smudged. Intermittently, scenes of the portly Soho observing art in a museum based loosely on the Johannesberg Art Gallery alternate with the lonely gentleman wandering through an abandoned, forlorn mining field. Eventually, the fruit in a still-life painting vanishes, an ocean pours out of a marine landscape painting, sculptures crumble, walls fall, and the entire museum collapses. Soho is left in the field, looking down into a grave at a man still tap-tap-tapping on a rock and hoping for gold.

The chamber opera has a cast of nine dancers and musicians (including Shepherd, who displays dazzling, minimalist brilliance on piano) and a libretto based on English, Russian, Hebrew poetry books, and a 1916 book of proverbs compiled by South African writer Solomon Platte. Some phrases are translated into Zulu, Setswana, Sesotho, and Xhosa, and are delivered in the vocal score using various techniques such as call-and-response style isicathamiya choral singing and umgqokolo, a form of overtone throat singing.

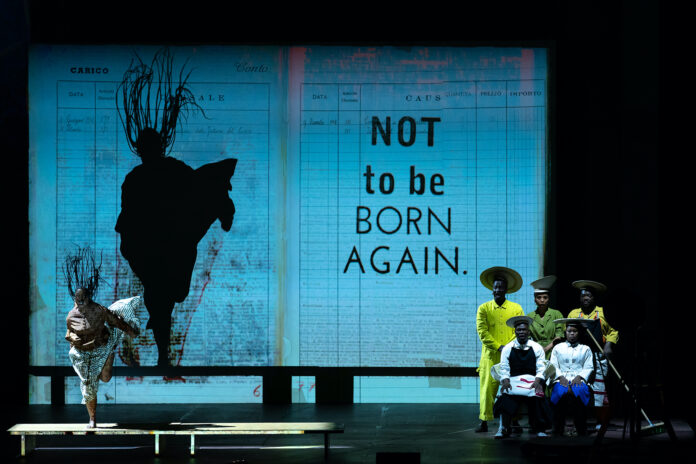

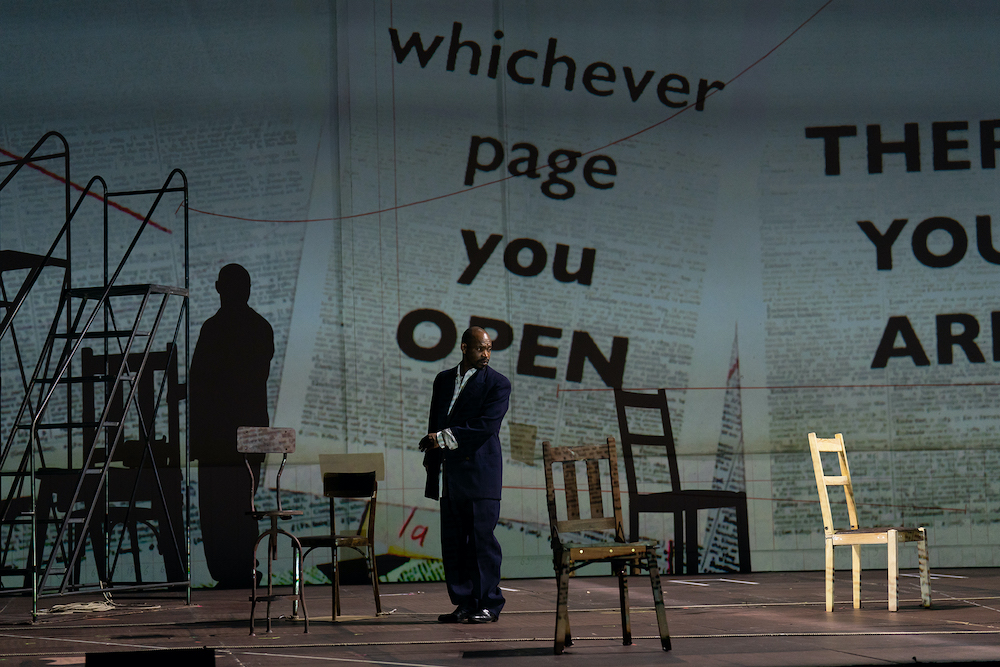

Images and ideas from the preceding film are collaged into artwork that splashes across the frontispiece curtain or backdrop in vibrant, bold projections that layer pronouncements and prognostications on top of old letters, travel documents, and more. Among them: “discard last year’s sock,” “resist the third martini,” “avoid meetings,” “beware of insects with mustaches,” “starve the algorithm,” “Heaven speaks in a foreign tongue,” and more ominously, “fresh graves are everywhere,“ and “my time is when?”

This is only the beginning of the aural and visual feast. Lighting is used most effectively (depending on the performer’s’ proximity to the lights) to cast enormous or tiny shadows of the dancers and singers. The shapes double the performers’ kinetic energy as they spin, fall, run, walk, or arch their torsos into anguished or ecstatic shapes. Similarly, spinning shadows cast by sculptures at moments appear abstract and at other moments reveal a tree, a human form, or the outline of oak leafs of the kind the ancient Cumaaean prophetess Sybil wrote upon to record her responses to people’s questions about their fates. The mythological story told is that she placed them outside of her cave home, where the wind caused havoc by scattering and mixing them. This left supplicants scrabbling through the leaves, never certain which fate was their own or that of another person.

The cast was universally impressive, but several days after the performance, certain mental images and echoes remain deeply engraved: Teresa Phuti Mojela performing the role of Sibyl with limitless physicality and depth, associate director and choral composer Mahlangu grabbing sheafs of paper and holding them to his ear in a desperate effort to receive an ungraspable message, singer-dancer Xolisile Bongwana creating an intense vibrato by bouncing his throat with one hand while singing a cappella.

It is impossible to encompass it all, except to say, if there is an opportunity in future to see Kentridge’s work, do. He made nine films during the pandemic, so there is that. If international travel is planned, in June 2023 his new animated film responding to Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 will be performed live at the Lucerne Festival in Switzerland. And a career retrospective at the Royal Academy of London in September that was delayed by the pandemic will finally be mounted. Short of those opportunities, there is only the hope that Cal Performances will find a way in future to soon herald the triumphant return of Kentridge and his talented collaborators to the Bay Area.